Filming Police: National Justice Project’s George Newhouse on the CopWatch App

A bare-fisted fight club operating in the NSW Northern Rivers region of Casino has recently come to the attention of NSW police, which has involved local youths partaking in illegal street fighting events and then posting footage and stills of the brawls on Instagram.

State law enforcement has warned the youths that posting themselves on social media in the commission of criminal activities could lead to arrest and prosecution. And with local authorities considering the practice to be escalating, it’s certain police will be monitoring activities online.

Indeed, last week saw the Queensland Police Service decrying a rising trend in youths filming their criminal activity and posting the footage on social media. And it announced that it’s expanding its Digital Intelligence and Evaluation Unit to monitor this on social media.

The National Justice Project (NJP) was keen to discuss these matters at a community meeting held in Minto on Tuesday, 21 March, which had a broader focus on relaunching the CopWatch mobile phone application and informing participants of their rights when filming police.

Holding police accountable

Tuesday was the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and NJP was relaunching CopWatch, a police accountability app, which allows users to film police, as well as providing a mechanism to alert others to their whereabouts if they’re being harassed by police.

CopWatch was being relaunched at South West Multicultural and Community Centre in Minto, as the application has recently been updated, and NJP was instructing adults and schoolchildren in attendance on how to use it.

Developed with people targeted by state police in mind, CopWatch has a particular focus on First Nations communities. And the NJP event involved informing community members of their rights when filming police, how to deal with video recordings and the lodging complaints.

CopWatch is modelled on US initiatives. The 2020 filming of the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd is a prominent example of the outcomes that can be achieved. And CopWatch has resulted in officers being convicted in this country, as well as in the dropping of charges against civilians.

“A survival tactic”

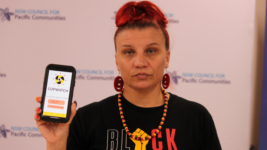

The National Justice Project event at Minto last Tuesday saw prominent Dunghutti, Gumbaynggirr and Bundjalung community advocate Elizabeth Jarrett explaining to kids in attendance that CopWatch is “a survival tactic for our youth of today”.

And a key message conveyed at the event is that if certain community members weren’t aware of their right to film officers while on duty, then many recent incidents of police misconduct and brutality would never have been scrutinised in the courts.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to National Justice Project director George Newhouse about the benefits CopWatch can deliver First Nations youths, the positive outcomes the app has already achieved and the importance of being cautious when loading content onto social media.

The National Justice Project is out at the South West Multicultural and Community Centre in Minto to relaunch CopWatch, which is a police accountability app that assists people in filming law enforcement.

As part of the event, you will be advising community members on their rights in relation to filming police.

So, firstly, George, what are members of the public allowed to do in terms of filming police officers on duty?

A lot of the work that we do is not about the technical use of a phone or how to video record.

Most of what we do is about safe interaction with police. It includes deescalation techniques and how to stand back and film for evidence.

It also provides information about how to respond to police when they intend to take someone’s phone or intend to delete information on one.

Most of the information is around the legality of filming police: how to film safely, how to deescalate, how to hold police accountable in law, how to keep kids in community safe and how to record for evidence.

Are there any laws governing filming?

Absolutely, and you have to be really careful about secretly filming individuals or recording conversations in most states and territories in this country.

But filming police in their normal duties in public is legal. And that’s what we teach people. But secretly recording on private land, that’s not on.

You need proper legal advice before you even start doing that because you could be committing a crime.

Why’s it important for these young people to know how to do this? Shouldn’t they be concerned with other things considering they’re kids?

A lot of these young people have regular negative interactions with police, and this is one tool that could empower and enable them to escape a criminal conviction because the fact that it’s disclosed to the court via independent video evidence could be exculpatory.

Many of these young people are already using cameras in public areas and we’re teaching them how to use them safely and legally and in a manner that won’t cause them harm.

Another matter I want to mention is that police are scouring social media for evidence they can use against young people. And one of the things we warn individuals about is to not upload any of this to social media without talking to a lawyer or a trusted adult.

Recently, the Queensland police formed a social media taskforce and it’s acted against mostly young people who upload evidence of criminal behaviour.

So, a lot of what we do is telling kids, and also adults, not to upload everything onto social media because you may be causing more problems than you’re solving.

So, how does the CopWatch application work?

We’re relaunching the app today. The first was originally designed by Atlassian, and it’s now been updated with the help of Thoughtworks, so that’s why we’re relaunching it, as it has new features.

It’s free to download on both Android and Apple devices. And essentially, you can download the app, and input some of the names and numbers of trusted friends, lawyers or your parents.

CopWatch does two things. First of all, if you are in trouble and having a negative interaction with police, it can immediately send, at the push of a button, a text message to trusted friends that you’ve preloaded, which says you’re having a difficult interaction with police.

And it also sends a geopin with your location asking for them to come and help.

So, the first thing it does is send preloaded warnings to trusted friends, lawyers or parents, asking them to come and help you.

The second thing it does is record straight into the cloud, where police can’t easily delete the footage. And it teaches you how to safely and legally record police interactions.

Do you tell kids that they should have their phone out and the app at the ready if police are approaching them?

Absolutely. The groups that we speak to have regular interactions with police. We’re not talking about kids in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney, who don’t often see or interact with police.

We’re talking about communities that are targeted and harassed by police. And these young people know exactly what we’re talking about, as they experience it daily.

The original version of the app was released in 2017. What are some examples of where CopWatch has come in handy since then?

We’ve had a number of examples. One is that after we attended Perth to do some CopWatch training, two young Noongar children filmed a police officer running down an Aboriginal man with a police car.

This incident was filmed from two different angles. That video evidence resulted in that police officer being charged and convicted of assault.

We have had other cases where young people have filmed their interactions and had the DPP and prosecutors drop criminal charges against them, which was the result of producing objective evidence.

And you’ve seen the power of videoing police in action in the George Floyd case.

The George Floyd case revolutionised the Black Lives Matter movement and it kicked off Defund the Police initiatives in the US, and it’s resonated around the world.

CopWatch really does continue in that tradition.

But we’re talking about law enforcement here, and the NSW police is a government-run entity supposed to be charged with looking after the community.

How are officers reacting to the community policing them with phones?

The police themselves say it is perfectly legal to film them during the course of their duty. When police are performing their duties legally and without violence, they have nothing to fear.

Good police should not be afraid of CopWatch. It is really only for situations where young people, in particular, are being targeted and harassed, often because of their race.

So, this kind of response is required. Young people who don’t have negative reactions with police, will never need to use CopWatch.

This is a defensive tool to help young people when they are being targeted or harassed by local police.

And lastly, George you’re about to embark on a day-long program at the South West Multicultural and Community Centre. And you’re out there with well-known First Nations community advocates like Elizabeth Jarrett and Paul Silva.

So, what will today’s event comprise of?

First of all, we’re going to be speaking to adults and explain the law to them.

Then after school, we’re going to be running a specific program for young people who have complained that they’re being targeted by police on how to improve their interactions with local police.

This isn’t about targeting police. Police are targeting young people, and CopWatch is a way for young people to protect themselves and improve their relationships.

Main photo: Dunghutti, Gumbaynggirr and Bundjalung community advocate Elizabeth Jarrett describes CopWatch as “a survival tactic for our youth of today”

Receive all of our articles weekly

Author

Paul Gregoire