Can Police Secretly Record You?

The law says that police are required to record interviews that take place at the police station, unless it is not practical to do so.

This requirement has been instrumental in tackling the problem of ‘verballing’ or fabricated confessions, which were once rife in the police force.

And importantly, when you are arrested and also before you are interviewed, you must be ‘cautioned’, or warned, that anything you say could be used against you in court.

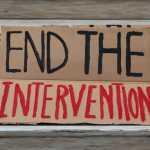

But what happens if police record you secretly, without giving you a caution, and you are tricked into saying something that could be used against you?

Can this evidence be used in court?

This is exactly what happened to one man who was arrested in connection with a murder and two house robberies.

The man, identified during the proceedings only as EM, was taken to the police station where he was adamant that he did not want to be interviewed.

Police repeatedly questioned him about two home invasions and asked if they could start recording.

EM said he had too much going through his mind, and that he wanted to talk in court, not to the police. He was then allowed to leave the station.

A few weeks later, two detectives picked him up from his house, but this time they did not take him to the police station, but to a nearby park.

They had successfully obtained a listening device warrant and each detective was fitted with a transmitter and recorder.

The detectives had a conversation with EM during which they repeatedly assured him that he was not being tricked and that he was not under arrest.

They said that they just needed his help to ‘clear a few things up’.

During the conversation, EM denied being involved in the home invasion, but he did make certain statements that could be interpreted as admissions.

At no point was he cautioned or told that he was being recorded.

Is the recording admissible in court?

Under section 17 of the Surveillance Devices Act 2007, police may apply to a judge or magistrate for a warrant to use a surveillance device.

This can be used if police believe an offence has been committed, or is about to be committed, and it is likely that an investigation into the offence is being, or will be, conducted.

The use of the device must be necessary to obtain evidence relating to the commission of the offence, or the identity or location of the offender.

In emergency situations, police may be able to use surveillance devices even before a warrant is issued.

Similar legislation was in place at the time that EM was interviewed, and despite the fact that police obtained a warrant EM argued that the evidence should not be allowed in the courtroom because this would be unfair.

What happened to EM in court?

In certain circumstances, such as those involving improperly or illegally obtained evidence, or where allowing evidence would be unfair to the defendant, the court may exercise its discretion to exclude the evidence.

But the High Court of Australia ruled that in EM’s case, the recording was admissible in court.

Four of the five justices found that making a secret recording through deception is not necessarily enough to make admitting the evidence unfair.

Rather, each situation must be considered in its totality, and the court must weigh-up a range of factors when deciding whether or not a certain piece of evidence is unfair.

Two justices went on to state that police trickery was acceptable in certain circumstances, because without it secret recordings could not be made, and without those recordings, police may not be able to secure enough evidence to solve a crime.

This is not good news for defendants, because it means that police can in certain circumstances get away with using deception as long as they are able to convince a magistrate or judge to grant a listening device warrant.

The lesson is clear: when it comes to the dealing with police, believe nothing and say nothing – because nothing is ever ‘off-the-record’.