A Forgotten Genocide: The Congo Free State

In the last decades of the 19th century, the European colonial powers laid claim to vast tracts of land on the African continent, expanding their spheres of influence and plundering natural resources. It’s commonly referred to today as the Scramble for Africa.

At the 1884-85 Berlin conference, the European powers met to negotiate control of the continent. Despite 80 percent of Africa being locally controlled at the time, the ambassadors at the meeting drafted random borders on a map of the continent, and created fifty countries.

A large part of the Congo Basin was handed over to Belgium’s King Leopold II. The colony – which was the personal property of the monarch – became known as the Congo Free State.

And although all the European colonial powers decimated the areas of the African continent they had control over, the genocide carried out in King Leopold’s name is usually pointed to as the most devastating.

The free state?

The Congo Free State lasted from 1885 to 1908. Historians estimate that during its time of operation, around 10 million Congolese people died. This accounted for half the population either being murdered or worked to death.

The colonisers’ mission was all about exploiting local resources, and the forced labour that could be utilised to extract them. The most important resource of the day was rubber, which was being shipped to Europe to make bicycle tyres.

The rubber terror

At the time the use of bicycles was skyrocketing in Europe and North America, and with it the demand for rubber. The Dunlop Rubber company was formed in 1890 mainly to produce the tyres.

It is yet another example of a popular consumer product being sold in the west that had an exploitative secret that was hidden from the buyers.

Rubber harvesting is harsh work. And the limited amount of Belgians stationed in the Congo needed to somehow force large groups of local people to carry out this painstaking labour in remote areas of the wilderness.

So the colonising force took full advantage of the lack of any laws that provided protections to the Congolese people, and set up a barbarous system to force the locals into submission that’s been dubbed Leopold’s “rubber terror.”

Wholesale barbarity

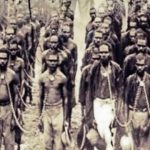

Under the King of Belgium’s rule, the Force Publique was established, which was an army and police force made up of a limited amount of officers from Belgium and local African troops. This private army was used to enforce the brutal conditions of the colony’s slave plantations.

A quota system was set up that required each village to produce a substantial amount of rubber, and to hand it over to the colonial overlords for free. If villagers failed to produce the required amount, merciless penalties were meted out.

A common punishment received by the villagers for missing their quota was to have their hands or feet amputated. It’s said that the imperialists employed this measure so as to save their limited ammunition.

As European demand for rubber further grew, a basket full of hands became the symbol of the waking nightmare that life had become for the Congolese people.

Further atrocities

However, the colonisers didn’t stop there. The officers of the Force Publique kidnapped Congolese people and held them captive so as to coerce their other family members into working harder. If villagers didn’t produce their quotas, then their loved ones would be killed.

One army officer reported that he’d cut off the heads of a hundred villagers, for failing to provide the army with enough food. He reasoned that it was a humanitarian act, as once he’d committed it there had been plenty of supplies provided.

And in this way, the hundred who died, had led many more to survive.

As the focus on rubber harvesting continued, villages no longer had the means or the time to cultivate their own food, and widespread famine broke out. And as starvation prevailed, so too did disease.

In the cases where Congolese people rose up and simply refused to work, they were killed and their bodies were strung up and displayed as a warning to others.

Eyewitness accounts

But, news of what was actually taking place in the Congo Basin eventually made it to the outside world.

A recent photo exhibition of the victims of the crimes perpetrated in the Congo was shown in the UK’s International Museum of Slavery. It served to remind today’s audience of just how dehumanizing unchecked power can become.

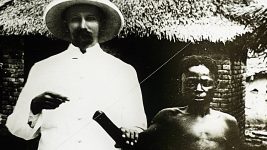

English missionary Alice Seeley Harris was the photographer behind the images that revealed the exploitation. And Joseph Conrad’s novel the Heart of Darkness was a fictional account of what he’d experienced in the Congo Free State and the “horror” of it.

It was these accounts, and others like them, that helped start the international outcry against the human rights abuses in the Congo.

A royal investigation

Leopold had been trying to cover up reports of the atrocities that were occurring in his personal colony. But it was an investigation by a British man named Roger Casement, and the accurate reports that he produced, which finally led to the demise of the king’s reign.

In a last bid to continue on, Leopold established his own commission of inquiry that was supposed to further cover up what was taking place. However, his handpicked commissioners actually reported that the atrocities were indeed occurring.

And it was due to this final report that King Leopold II was forced to sell his colony to the Belgian government in 1908.

On to independence

Under the colonial rule of Brussels, the area became known as the Belgian Congo. New laws and regulations were introduced to limit much of the abuses being perpetrated, but many continued.

After World War II, local Congolese people began rising up and calling for independence and the Democratic Republic of Congo was eventually established in 1960.

However, Congolese independence hero Patrice Lumumba – the nation’s first democratically-elected prime minister – was imprisoned by authorities and executed early on. And then the nation was ruled by the corrupt military dictator Mobutu Sese Seko for over twenty years.

The ravages of colonialism don’t just exit a country when the colonisers do. And the impact of colonial human rights abuses can often carry on for decades afterwards.