Explaining the Rohingya Crisis: An Interview with the ARNO

The UN Refugee Agency reports at least 420,000 Rohingya people have fled across the border from Myanmar into neighbouring Bangladesh since violence erupted in their homelands in late August. The refugees are now living in makeshift camps in the Cox’s Bazar district.

IOM, the UN Migration Agency, has called for a coordinated response to the flow of Rohingya people into the Bangladeshi coastal region, as it’s unprecedented in terms of speed and numbers.

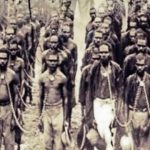

The Rohingyas are a mainly Muslim minority from Myanmar’s north western state of Rakhine, formerly known as Arakan. Thousands began crossing the border as the Myanmar security forces have been carrying out systematic ‘clearance operations’ – torching villages and murdering members of the minority group.

The Myanmar military, known as the Tatmadaw, began its most recent operation ostensibly in response to a series of coordinated attacks on police posts and an army base carried out by Rohingya insurgents on August 25.

But by all credible accounts, the response is completely disproportionate and many regard it as a crime against humanity.

Communal violence

On Wednesday, hundreds of Rakhine Buddhists tried to block an International Committee of the Red Cross aid shipment being sent to Rohingya people in the north of the state. The protesters tried to stop a boat that was being loaded with 50 tonnes of aid at a dock in the state capital of Sittwe.

For decades, tensions have simmered between the Rohingya and Rakhine Buddhists: the majority population of the state. Sittwe was one of the flashpoints of the 2012 riots, which drove around 140,000 Rohingyas into internally displaced persons camps throughout the region.

A stateless people

Myanmar denies citizenship to the estimated 1.1 million Rohingya living in the country’s most impoverished state. The 1982 Citizenship Law does not recognise the Rohingya as a national ethnic group, unless they can provide evidence that their ancestors were in the country prior to 1823.

This is despite their being evidence that the Rohingya were living in the area between the mid-15th to late 18th centuries, if not more than 1,000 years ago.

The government of Myanmar refers to the Rohingyas as Bengalis, which effectively denies them their separate ethnic identity. The term is considered derogatory by the Rohingya people.

Nothing to hide

Aung San Suu Kyi became Myanmar state counsellor – the de facto head of state – in November 2015, when the nation held its first free elections in 25 years.

The Nobel Peace Prize winner has come under international criticism for her silence over the unravelling humanitarian crisis, which the UN has described as “textbook” genocide.

Last Tuesday, Ms Suu Kyi broke her silence during a public address she gave in the nation’s capital Naypyidaw. However, she refrained from criticising the military and its operations, and tactfully pointed out that “more than 50 percent of the villages of Muslims are intact.”

A voice for the oppressed

The Arakan Rohingya National Organisation (ARNO) is a political organisation based in London. It is seeking the right to self-determination for the Rohingya people, the preservation of their history and the repatriation of all refugees.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® spoke with Ronnie, a senior member of ARNO, about what’s happening on the ground in Rakhine state, when the persecution of the Rohingya actually began, and the silence of a Nobel laureate.

Firstly, Ronnie, over 400,000 Rohingya people have fled across the border into Bangladesh since the violence erupted in late August. A top UN representative has described the situation as a “textbook example” of ethnic cleansing.

What’s actually happening in Rakhine state at the moment? And is this the worst escalation of violence the region has ever seen?

The Rohingyas have been subjected to persecution, violence, abuse and have been fleeing the region since the 1962 Burmese coup d’état by then General Ne Win.

However, we have never before seen such extreme brutality and massacre carried out by the military, government officials and the local Rakhines.

They have indiscriminately killed villagers and burned villages, raped women and slayed infants and children.

As we talk, the number of people taking refuge in Bangladesh is nearing 500,000 and hundreds of thousands more are stuck in the Myanmar jungle, paddy fields and zero border area, starving and dying.

The majority of the refugees are women, children, and old people. Where are the Rohingya men amidst those refugees?

It is a genocide in the making.

Satellite images have revealed that over 200 Rohingya villages have been burnt to the ground.

Are these burnings being carried out solely by the Tatmadaw, or are local Rakhine Buddhists involved? And is this a sign that security forces are trying to rid these areas of their local Rohingya populations for good?

Yes, the burnings of the villages are being carried out by the Tatmadaw, and in coordination and cooperation with local Rakhine Buddhists and government officials.

I recall in 2012, when Burma’s then president Thein Sein asked the UN refugee agency to place ethnic Rohingyas living in the country in refugee camps or send them abroad.

This is exactly what they are doing.

Aung San Suu Kyi has notoriously said little about the violence in Rakhine since it initially broke out in October last year.

However, on Tuesday, she gave a speech, where she claimed it was difficult to “find out what the real problems are.”

What do you think about the response of Ms Suu Kyi to the humanitarian crisis?

We believe she is equally responsible for the atrocity crimes in Myanmar. And we’re outraged by the highly contentious and ambiguous speech Suu Kyi delivered before the diplomatic community on September 19 in Naypyidaw.

She made numerous disingenuous excuses that fail to address the crisis, and the untold sufferings of the Rohingya people.

Without condemning the Myanmar military and collaborators, Suu Kyi tried to deflect the blame for the mass atrocity crimes and told the diplomats that she was unaware of the facts as to why Muslims fled to Bangladesh and that while many villages had been destroyed, more than half were still intact.

It is a hypocritical statement that suggests that she is too morally bankrupt to take a stand on the Rohingya genocide.

The Myanmar foreign ministry has suggested the August 25 attacks were carried out to sabotage the release of the final report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State. The commission was chaired by former UN secretary general Kofi Annan.

What did you think about the findings and recommendations that were made in that report?

We think the findings and the recommendations in the Kofi Annan report are reasonable and will solve the Rohingya crisis to a very certain stage.

We have welcomed the report and in our latest press releases we have urged the implementation of those recommendations.

A group of Rohingya organisations filed a communication with the International Criminal Court (ICC) in December 2015. It requested the court exercise its jurisdiction as the Rohingya people are stateless and have no legal recourse in Myanmar.

What was the response of the ICC?

The ICC finally responded last month and said it does not have jurisdiction on the mass atrocity crimes committed against the Rohingyas.

The Rohingya continue to have no access to justice and therefore do not have any redress in Myanmar if they are prosecuted.

Acts of mass atrocity and genocide against the defenceless Rohingya and other minority civilians can never be a purely internal matter of Myanmar. These acts have been ongoing for over thirty nine years.

The UN and the international community have a responsibility to protect and should intervene to save thousands of lives and protect human security.

Rohingya people of older generations can remember a time when they lived side by side in peace with Rakhine Buddhists.

When did the situation begin to decline so the Rohingya people started to become a persecuted minority in their homelands?

We think immediately after General Ne Win took over power. He started planning his vision of the “Burmanisation” – to make all ethnic people Burmans and Buddhists – of the whole of Burma.

However, the situation began to decline in the late 70s. And legally Rohingyas were rendered stateless in their own state after the introduction of the 1982 law.

Henceforth, all their legal rights were taken away.

And lastly, Ronnie, what does your organisation prescribe as the positive way forward for the Rohingya people?

The Arakan Rohingya National Organisation is one of the representative organisations of the Rohingya people of Arakan, Burma, based in London, the United Kingdom. It is a broad-based organisation of the Rohingya people that emerged in 1998.

We believe in a peaceful political solution. We are hopeful that the international community will uphold human rights, peace and democracy against economic and political gains.

As we said, it is a genocide in the making and the international community and actors must unite to end this.

Otherwise, persecuted minorities and groups will lose faith in democratic values and the principles of human rights will only become a joke.