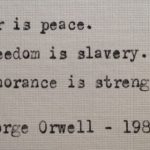

Welcome to 1984: The Government’s Relentless Assault on Democracy

Many social commentators have drawn comparisons between George Orwell’s dystopian novel ‘1984’ and the pervasive nature of surveillance in a several modern nations, labelling the book as prophetic rather than emphasising that it is a work of fiction.

Orwell’s book was written 70 years ago in 1949, but perhaps never has it been as relevant as in modern day society, from countries with traditionally poor human rights records such as China to so-called ‘Western democracies’ such as Australia.

China’s Social Credit System

Signifying the pervasiveness of surveillance in China is the nation’s social credit system.

Chinese citizens are now ascribed ratings based on their conduct in the eyes of the state.

It has been reported that conduct such as criticising the government or state policies online and spending too much time playing online games can cause a person’s credit rating to plummet.

And in some cities, photos of these ‘bad’ citizens are pasted on high-tech billboards to publicly shame them. Even the act of jaywalking can lead to this type of shaming.

Reports suggest the Chinese government has gone as far as to install an embarrassing ringtone on the phones of those with low scores, shaming them every time they get a call in public.

These ‘undesirables’ may even be turned away from an airline counter and forced instead to take a slow train. But this is just the beginning.

A low social credit score can lead to exclusion from well-paid jobs, and make it impossible to get a house or a car loan.

A person’s profile can be posted on a public blacklist for all to see, and an app has already been created which reveals the personal information of those people, including their full name, any court-case numbers and the reasons they have been labelled untrustworthy.

The system is almost entirely fuelled by technology, and the final rollout is expected to be in place nationwide by 2020.

Recognition technology

Police in China have also been issued with hi-tech ‘smart glasses which use facial recognition technology to identify people whose appearances correspond with images on government databases, including those of regular citizens.

One man was recently snapped by an automated surveillance camera, which takes a photo when a driver moves, and was fined for using what artificial intelligence determined was a mobile phone while driving, but he was actually scratching his face.

He lost points on his licence and was fined the equivalent of about $10, but he fought hard to have the penalty notice and fine overturned – because the implications of such a blight on his social score were potentially severe.

And while Human Rights Watch has described the measures implemented in China as “chilling”, Government representatives points out that they are not dissimilar to those in place in the ‘West’.

The same technology exists in Australia

Indeed, commentators have made a number of comparisons between Australia and the Chinese regime since the raids on journalist Annika Smethurst and the offices of the ABC earlier this month.

The raids have shone a spotlight on the pervasive powers of our Governments to access information and prosecute whistleblowers, as well as journalists who publish information about misconduct in Government departments.

The intimidating nature of the raids has been highlighted, as well as powers such those given to the AFP to “add, copy, delete or alter” material on the ABC’s computers.

Our Governments have also sought to implement facial recognition techology but trial have revealed it to be highly inaccurate and unreliable.

In recent years, police in New South Wales have been the beneficiaries of hundreds of laws which increase state control at the expense of legal safeguards and protections – from laws which broaden police powers of arrest, to those which allow officers to control peoples’ movements and associations, to laws which permit them to detain suspects for longer periods of time without charge, and those which allow police to ‘shoot first and ask questions later’ and give them immunity from both civil and criminal prosecution during ‘special intelligence operations’, even if they commit heinous assaults against innocent people in the process.

And in a first for the Western world, metadata retention laws have come into effect requiring internet service providers to store the personal data of customers for at least two years and release it to a whole host of law enforcement agencies upon request without them having to obtain a warrant. Those laws have already been misused in a range of ways.

The federal government has even passed legislation to enable the creation of a national biometric database using driver licence photos supplied by states and territories, which could be used for any number of intrusive purposes.

Such laws are almost invariably passed under the guise of protecting against terrorism or organised crime, but many believe they do little more than curtail important civil liberties such as privacy, freedom of movement and association, the right against detention without proper cause and the ability to seek accountability for personal abuses.

Calls for a Parliamentary Inquiry

Perhaps an upside of the recent media raids has been that they have triggered debate about the scope of laws which increase the powers of the state at the expense of individual freedoms and legal safeguards.

That debate has now led the federal Labor party – which, incidentally, has supported the vast majority of those laws – to call for a parliamentary inquiry, which it says would look into whether the encroachments on civil liberties are necessary in order to protect against outside threats.

We can only hope that a meaningful review takes place, and that laws are revised to enable criticism of the government without fear of criminal prosecution, and reinstate at least some of our lost civil liberties.