Uprising in West Papua, as Calls for Independence Grow

The widespread unrest in occupied West Papua continues. The mass demonstrations across the region have moved into their third week, as protesters send a clear message to Indonesia that locals want their right to self-determination upheld.

The uprising began on 18 August, following the abuse and torture of West Papuan students in Surabaya, East Java at the hands of Indonesian security forces. And as the protests have grown, Jakarta has responded by deploying more troops and cutting access to the internet.

On Sunday, three West Papuan students were shot in their dormitories by Indonesia police in the Jayapura suburb of Abepura. This follows the death of at least six locals last week, when Indonesia forces fired upon peaceful protesters occupying the regent’s office in Deiyai city.

The demonstrations are the largest seen in West Papua in almost two decades. And they come as a months-long crackdown by Indonesian forces in the highland regency of Nduga has led to the displacement of tens of thousands of villagers.

And according to West Papuan independence protesters, these actions are set to continue right up until the 74th session of the UN General Assembly that commences on 17 September, as they want their calls for an internationally supervised referendum on independence to be heard in New York.

An end to colonisation

“It started when Indonesian military and police attacked West Papuan students in Java. They used racist language and called West Papuans ‘monkeys’,” explained United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) spokesperson Jacob Rumbiak.

“Of course, this is not new for West Papuans, because the language of racism has been ongoing for more than 50 years with West Papua being a colony of Indonesia,” the political leader living in exile in Australia added.

Although, the spontaneous demonstrations began as a reaction to the racist incidents in several parts of Java, Rumbiak explained that they’ve taken on a greater significance as the Indigenous population calls for an end to oppressive Indonesian rule.

And Mr Rumbiak is all too familiar with the iron fist of the Indonesian military in his homelands. Whilst teaching at Jayapura’s Cenderawasih University in Papua province, the academic joined the nonviolent resistance, only to be sentenced to life imprisonment on charges of subversion.

“Maybe bloodshed will be coming, because Jakarta said they can’t allow West Papua its freedom,” Mr Rumbiak warned Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “But, in West Papua, it is their right and the struggle will continue.”

“We are not red and white”

On 17 August, 40 West Papuan students were arrested in Surabaya for allegedly damaging an Indonesian flag. On the following day, protests erupted in Manokwari, the capital of West Papua province, after a video circulated showing Indonesian troops calling students “monkeys”.

Thousands of locals took to the streets across the two provinces of West Papua and Papua. In a divide and rule tactic back in 2003, Jakarta split the region into two. And in Manokwari, the ongoing demonstrations have seen government buildings set on fire, including the parliament.

Following the shootings at the student dormitories in Jayapura last Sunday, Jakarta said it would be deploying a further 2,500 troops, on top of an initial 1,200 that were sent in towards the beginning of the protests. And an internet blackout was imposed in the region a fortnight ago.

Indonesian troops fired upon peaceful protesters in the city of Deiyai in Papua province on 28 August. Mr Rumbiak said that initial death toll of six West Papuans has now risen to eight in an incident being described as the Deiyai massacre.

The Act of No Choice

As part of the 1962 New York Agreement, the United Nations handed over the administration of West Papua to Jakarta in 1963. This followed a brief period of UN administration, after the Netherlands gave up its colonial rule of the region.

The United Nations stipulated that as part of the handover agreement, the Indonesian government had to hold a referendum to allow the West Papuan people to decide on whether they wanted to remain under the control of the foreign power or become an autonomous nation.

So, in 1969, Jakarta handpicked a mere 1,026 West Papuans to take part in the UN brokered Act of Free Choice. And under the threat of military reprisal, all of those selected voted in favour of remaining an Indonesian colony.

Over the time of Indonesian occupation, 500,000 West Papuans have lost their lives, with countless others incarcerated. And a transmigration program has resulted in West Papuans accounting for 49 percent of the local population, whereas back in 1971, they made up 96 percent.

Time for justice

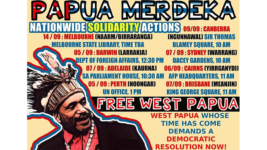

Mr Rumbiak made clear that the unrest in West Papua is going to continue right up until the UN General Assembly meets in two weeks’ time. He said the protests will increase, as they call on the UN Human Rights Council to visit the region, as well as to send in a UN peacekeeping mission.

In January, ULMWP chair Benny Wenda handed the West Papuan People’s Petition to the UN Human Rights high commissioner. Around 1.8 million West Papuans – 70 percent of the population – risked their lives to sign the document, which calls for an internationally supervised vote on self-determination.

And at last year’s meeting of the UN General Assembly, the heads of state of Vanuatu, the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu called for action on West Papua. Vanuatu’s prime minister Charlot Salwai told the meeting that West Papuan decolonisation must remain on the agenda.

“I hope all Pacific countries will open their mouths when debating at the UN meeting,” Mr Rumbiak concluded. “West Papua and Indonesia must sit and talk in New York to make a clear decision on West Papua’s future.”