Testifying to West Papuan Atrocities: An Interview With Academic Jason MacLeod

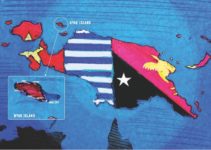

Widespread civil unrest broke out in Indonesian-occupied West Papua on 18 August. And it continues on to this day. In the region that’s been under the repressive rule of Jakarta since 1963, the mass protests were sparked by racist attacks on Papuan students in Surabaya, East Java.

Indonesian president Joko Widodo responded to the uprising by sending in thousands extra troops. This led to an escalation in violence, with forces killing dozens of unarmed civilians. The worst occurred in the city of Wamena in late September, with 33 Papuans losing their lives.

While revolt is always simmering in West Papua, the scope of the latest demonstrations is unprecedented in recent times. It’s the greatest unrest the region has seen in almost two decades, with the last violence on this scale being the Byak massacre.

Back in July 1998, local Melanesian protesters raised the Morning Star flag above a water tank in Byak city, on an island in the north of the region. This resulted in a vicious crackdown by Indonesian security forces that left 200 civilians dead.

“We want the world to know”

“We want to testify about the injustices of the 1998 Byak Massacre,” states the collective voice of survivors on the third track of We Have Come to Testify. “We want to testify about the killings and the beatings with rifles. We want to testify about the people who were disappeared.”

These words are spoken by Kamilaroi-Tongan musician David Leha – professionally known as Radical Son – on the third track of the recently released Testify CD. It and the accompanying booklet contain the testimonies of survivors and eyewitnesses of the 1998 massacre on the island of Byak.

As the perpetrators of this mass killing have never been brought to justice, a Citizens’ Tribunal was assembled in Australia in 2013 to give voice to and document the testimonies of those who lived through the violence.

Produced by renowned Australian songwriter David Bridie, We Have Come to Testify presents the witness accounts of what happened back in July 1998 set to music. And the project involved a range of performers and musicians from West Papua and throughout the Pacific region.

Complicit support

Yet, as Jakarta was unleashing the full force of its military upon the Indigenous people of West Papua last month, the Australian armed forces were in the Indian Ocean carrying out a joint naval training operation with Indonesia, known as Exercise Cassowary.

Indeed, the Australian government seems quite comfortable with the decades-long repression in West Papua. It signed the 2006 Lombok Treaty, which is a security agreement between the two nations that recognises Indonesian sovereignty over the Melanesian territory.

Co-chair of the West Papua Project Jason MacLeod asserts that despite the treaty, Australia could be doing more. The local academic has long been a supporter of the West Papuan struggle. And he also lectures on civil resistance at Sydney University’s Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Jason MacLeod about what actually took place in Byak at the time of the massacre, the atrocities that are unfolding at present in the region, and the choice the Australian government has to make make regarding the current unrest.

Firstly, Jason, how did you come to be involved with We Have Come to Testify?

I went to West Papua for the first time in 1991. I was 19 years old. And it changed my life.

I came back from that trip thinking, why hadn’t I been told? Why didn’t I know about this story? Why didn’t I know the extent to which the Australian government and corporations were involved? I kept following the issue, and through relationships, got drawn into the struggle.

I’ve travelled to Byak on a number of occasions. And my colleague, Dr Eben Kirksey, was a witness to the massacre. He reached out and asked me to work with him to organise the Citizens’ Tribunal.

What did the project involve?

We worked very closely with our colleagues from Elsham. They did the original human rights investigation back in ‘98.

We had West Papuan human rights lawyers. And most significantly, we had survivors of the massacre, and eyewitnesses.

These survivors were both West Papuans living in Australia and those we brought out. They were a number of survivors who are still living in West Papua. They testified as well.

We had significant support from the legal fraternity too. So, it was a big deal.

You wrote the section in the booklet outlining the events that were the 1998 Byak Massacre. What actually happened?

There was a massive movement towards democracy in Indonesia, as the dictator Suharto was overthrown by a popular uprising.

So, there was this kind of euphoria in Indonesia at the time. It was like a lid was being lifted off this repressed anger and resentment. And in West Papua, people thought they could finally express their aspirations.

There was a guy by the name of Filep Karma, a civil servant. He wanted to raise the Morning Star flag: the symbol of West Papuan independence. And he wanted to keep it flying.

He organised a demonstration, and people joined in. They kept the flag flying on the water tower in the centre of Byak city for four days. And then the Indonesian military came.

They came in on 6 July, before dawn. They opened fire, shot dead many protesters around the flag and dispersed the group.

They worked with militia to round up and detain other people involved. And then those people were basically held and tortured. A number were taken onto three warships that were anchored offshore in Byak, and there the killings continued.

The bodies were dumped in the sea. For days afterwards, the cadavers washed up. And they were showing signs of mutilation and torture.

As a result of all of this, not a single army officer was charged. However, a number of the survivors were charged and were thrown into prison.

The commander at the time was General Wiranto. He was head of the armed forces. He is still in power today.

He’s currently the coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs. That’s the most powerful position in the Indonesian government. And he’s the same guy who’s presiding over the violence in West Papua right now.

The massacre happened two decades ago. Why is the We Have Come to Testify project – the CD and booklet – important right now?

It’s very recent history. There’s been no justice since. That would be reason enough. But, what makes it even more important is the same patterns of violence that happened in 1998 are occurring right now in West Papua.

The same actors are involved. Wiranto being one of them. And the massacres have continued. There has been no justice for any of the victims, the survivors or their families.

These massacres are not just in Byak. There are other places in West Papua. It’s in Paniai. It’s in Wasior. It’s in Abepura. It’s in Ngduga. It’s all over the country. The same kind of violence continues to take place.

And lastly, as you’ve just mentioned, there has been unrest, demonstrations, and massacres in West Papua over the last month. Jason, what are your thoughts on what’s taking place at present? And where could it all lead?

It’s a really disturbing situation. West Papua at the moment has the potential for mass atrocities. There’s a couple of really distressing indicators.

There’s a rise of racist hate speech towards Papuans that’s effectively being condoned by the state.

You have the Indonesian police and military organising militias and encouraging Islamic jihad groups to travel to West Papua. They are currently in a number of places.

The internet is being throttled. Diplomats are being locked out from visiting the country. So, it’s much harder to get news out. All of these are indicators that we could see much more violence.

And at the same time, West Papuans won’t back down. They’re absolutely determined to be free. And that can’t be stopped. The state might violently repress it. But, in doing so, Papuans’ desire to take back their country only deepens.

The Australian government’s got two choices. Either they can abide by international agreements with the Indonesian government – like the Lombok Treaty – and not say anything, or they can insist on the need for talks. The root causes of the conflict are political, and they need to be addressed.

At the very least, the Australian government should support the Pacific Island Forum’s call for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to visit the country.

And then, the government could just stop training the perpetrators, which are the police and military. Currently, we’re training them, and not saying anything.

The situation is not looking good. But, there are a number of things the Australian government and people could do.