COVID-19 Protest: Fines Issued Despite Drivers Remaining in Cars

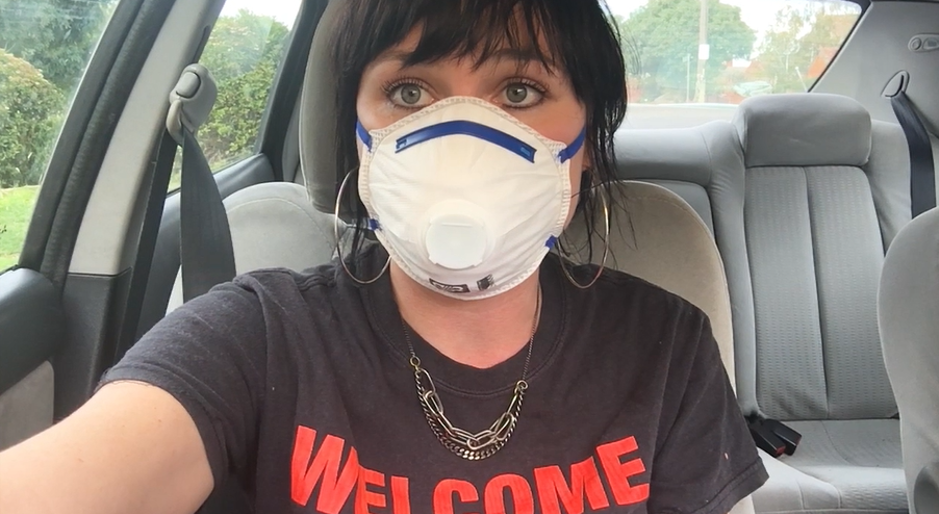

The Refugee Action Collective (RAC) Victoria announced last week that it would be going ahead with a car cavalcade protesting the continued detention of immigration detainees at facilities and hotels nationwide, despite police warnings that demonstrators could be hit with COVID-19 fines.

The rally was drawing attention to the life-threatening conditions detainees now face. While organisers labelled the ban hypocritical, as the limit of two people from the same household per car was much safer than shopping, travelling on public transport and non-essential work that continues.

However, no one expected Victoria police to turn up at the house of RAC’s Chris Breen two hours prior to the Good Friday event and arrest him. And nor was it anticipated that officers would then apply for a search warrant and execute it at his house, seizing computers and phones.

While Breen spent the next nine hours at the local police station, the rest of the protesters met in a carpark, where undercover police showed up and tried to prevent them continuing on to the protest site, which was out the front of Preston’s Mantra Hotel, where 70-odd refugees are now being held.

Then as the cavalcade vehicles arrived in the vicinity of the hotel, they were met by a huge police presence. Officers ordered the drivers to pull over and took the protesters names and numbers. Twenty six $1,652 COVID-19 fines – amounting to close to $43,000 – will now be posted out.

Provoking a peaceful protest

“I’ve been charged with incitement – so inciting the protest – not under the health regulations. They’ve seized all of our computers and my phone,” explained Chris Breen, a spokesperson for RAC Victoria.

“Which is strange, because none of the actual facts are in dispute,” he told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “I am not disputing that I am an organiser. I am not disputing that I put up the Facebook page, which is why they’re saying they need the computers as evidence.”

Section 321G of the Crimes Act 1958 (VIC) contains the offence of incitement, which involves an individual inciting “any other person to pursue a course of conduct which will involve the commission of an offence”.

While section 321I of the Act outlines that if the offence the inciter has encouraged another to perpetrate has a fixed penalty, the person convicted of incitement shall be liable to that same penalty. So, if found guilty, Breen will be hit with a $1,652 fine.

“It seems like an incredible amount of effort to go to,” Breen said of his arrest and the subsequent raid of his residence. “If it was just the fine, they could have let me go to the protest and fined me there.”

“It does seem like it was intended to intimidate,” he added.

Mixed messages

Darebin police inspector Tom Ebinger told the Herald Sun that the convoy drivers had been questioned in regard to breaching the COVID-19 restrictions. And he emphasised that protesting was not an activity that was exempt from the prohibitions in place during the pandemic.

Ebinger further suggested that the “activity should have probably been postponed until the pandemic was over”. And the rather macabre irony in his statement – that protesters were trying to ensure that the refugees’ lives were saved during the crisis – was most likely lost upon the officer.

But, the shutdown of the Preston car cavalcade highlighted another issue that critics have been raising since the stiff penalties began to apply to social distancing and self-isolation restrictions, which is there’s been no consistency in their policing.

On the day prior to the RAC car protest, the No Worker Left Behind car convoy rallies took place in Melbourne and Sydney. And while two Victoria police officers turned up at the Melbourne rally, they did so at the last minute – like it was an afterthought – and they only pulled over a few vehicles.

Breen was a participant in the earlier protest organised by the United Workers Union. His car was one of only four that were stopped at the tail end of the convoy. And the long-term activist said he and some union organisers were warned about breaching the regulations and then moved on.

From the legal eagles

“It’s outrageous,” declared Erin Buckley, a founding member of Melbourne Legal Activist Support (MALS). And she added that the authorities ought to be policing these new laws in a manner that’s consistent with the rights contained in the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities (VIC).

MALS was supporting RACS with its Detention Is a COVID-19 Risk, Free the Refugees car convoy rally. It outlined that while the pandemic prohibitions are necessary, the restrictions on freedoms that they involve should be limited and non-discriminatory.

“All of these inconsistencies in the application of these police powers speak to the need for very clear directions to be made to police in regard to them,” Ms Buckley continued, adding that these measures are supposed to be about protecting public health.

The lawyer suggests that those fined should contest their penalties as it’s highly likely that the laws have been misapplied in this instance. And if an initial review of the fine is unsuccessful, it can always go before a magistrate.

Buckley said that Victoria police is well-aware that applying the law shouldn’t infringe upon citizens’ rights. However, she’s not so sure all of its officers are clear on this. “They need to be giving those directions for their own members protection, as well as the community’s protection,” she said.

Silencing dissent

“We were protesting because the threat of COVID-19 makes the release of the refugees at the Mantra – and actually the 1,400 refugees in centres across Australia – urgent,” Breen explained. “These are like cruise ships on land. There is no way people can practice social distancing.”

Currently, there are close to 70 long-term offshore refugee detainees from Manus and Nauru being held in the Mantra Hotel. They were brought across to Australia under Medevac. And they all have chronic illnesses, which make them more at risk if they contract COVID-19.

There are around 80 guards watching over the men. These people come and go from the hotel on a daily basis. The guards don’t practice social distancing, nor do they wear masks or gloves. And the refugees aren’t able to practice distancing and they’re not supplied with protective gear or products.

“They’ve committed no crime. And now they’re lives are really being put at stake,” Breen concluded. “There was nothing unsafe about our protest. And we do think these laws are being used as an excuse to crack down on political protest.”