Morrison Insists on Mobile Phone Tracing App Before Controls Can Be Eased

In his COVID-19 update on 16 April, prime minister Scott Morrison set out seven “precedent conditions” of a forward planning framework that if set in place could result in an easing of pandemic restrictions in four weeks’ time.

The fifth condition on the list is “advanced technology for contact tracing”. This entails a downloadable phone app that can track people a user comes into contact with, and if any these contacts fall prey to the virus, that user will then be notified.

Modelled on a similar app being used in Singapore, the “tracing app” should be ready for rollout within a fortnight. And while participation in the contact monitoring scheme will be voluntary, it does require a 40 percent opt-in rate to be effective.

Using pre-existing Bluetooth technology, the app would store the anonymised details of all people an individual has come into contact with for at least 15 minutes. And if a person is subsequently notified that they’d been in close proximity to a COVID carrier, they wouldn’t be told who it was.

But, despite assurances that it will be voluntary and unidentified data, many privacy-minded individuals felt their hairs stand on end when they heard about the scheme. And this sensation was only compounded when they realised that Apple and Google are getting in on the action as well.

Habit-forming

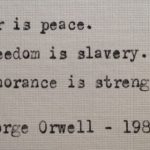

Of course, we’re currently in the midst of a life-threatening pandemic, so it’s hardly likely the Liberal Nationals government would take this as an opportunity to enhance its controls over the general populace. Or is it?

Civil liberties advocates have warned for years that since 9/11, successive governments at both the federal and state level have passed dozens of pieces of counterterrorism legislation that have been slowly eroding the rights of all, regardless of which side of the law they sit on.

A quick perusal of some key bills reveals that getting its hands on our private data is of keen interest to government. Take our metadata. Since late 2015, telcos have been required to store it for a period of 2 years, while law enforcement and intelligence agencies can access it without a warrant.

The Coalition hasn’t stop there though. In 2018, Peter Dutton revealed his Assistance and Access Bill. It enhanced the government’s ability to reach inside citizens’ encrypted message boxes, so it can read what’s there without the hassle of coding.

Indeed, right before the coronavirus pandemic swept into town, the old home affairs minister was making another broad general reach, this time spruiking his on-again, off-again proposal to turn the nation’s foreign cyber spying agency – the ASD – upon domestic targets.

A built-in function

Not wanting to be left out in the cold by Asian tech-heads, the US goliaths Apple and Google announced on 10 April that they’re getting into bed in order to design their own COVID-19 monitoring app, which is going to operate in much the same way as its Singapore counterpart.

A document issued by the two tech companies outlines that the app will not “collect personally identifiable information or user location”, the list of contacts will never leave an individual’s device, and it will only be used by “public health authorities for COVID-19 pandemic management”.

“The problem is that the Google-Apple unholy alliance’s proposed “solution” is not yet well or adequately defined,” said Civil Liberties Australia (CLA) CEO Bill Rowlings. “And each company has been guilty of privacy invasions in the past.”

“Provided their solution during the pandemic panic is temporary, a voluntary solution that a device owner could choose to install or not, and it is designed so that it automatically removes itself when the emergency is over, it may be acceptable,” Rowlings suggested.

However, the Apple-Google development team is hoping to eventually incorporate this functionality into their operating systems, so they can bypass the need to have it downloaded. And this could take months to do, which raises questions around why to proceed if the scheme is solely for COVID-19.

So, what’s it matter, anyway?

Many questioned what the issue was around having our metadata accessible to authorities prior to its required storage, as it doesn’t entail message content. Metadata is the date and time of calls, texts, emails, and internet sessions, as well as details of those being communicated with.

But, experts state that quite a profile can be built up about an individual via their metadata. It can reveal who they associate with, what their political persuasions are, their health status, details about familial relations and their financial situation.

So, back to the tracing app, one might question what could be done with a list of anonymous contacts on a device. However, there’s always the possibility of re-identifying data, which could then reveal contacts outside of digital communications, which metadata fails to do.

Time to take it back

Rowlings warns that while there’s the very real danger of around 1 percent of people dying as a result of the virus, there’s also the equally legitimate issue that 100 percent of the population is in danger of having its privacy invaded and civil liberties lost on a permanent basis after the pandemic.

That is if “we citizens don’t insist our politicians and police wind back the emergency intrusions,” he told Sydney Criminal Lawyers.

The former journalist pointed to a range of restrictions that a few weeks ago wouldn’t have been conceivable: bans on beaches and playing golf, threats of huge fines, drones monitoring compliance, as well as a stipulation to walk around the ACT’s Lake Burley Griffin in a clockwise direction.

“There’s a clear trend in just a few weeks of loss of liberties and choice and pervasive intrusion into our freedoms,” Mr Rowlings said, “as well our parliaments being shut down, so our democracy is shot to pieces.”

“We have a major battle on our hands over the next year or so, just to return to what was the rights and liberties status quo very recently,” he concluded.