Now Is the Time for First Nations Justice and Systemic Change

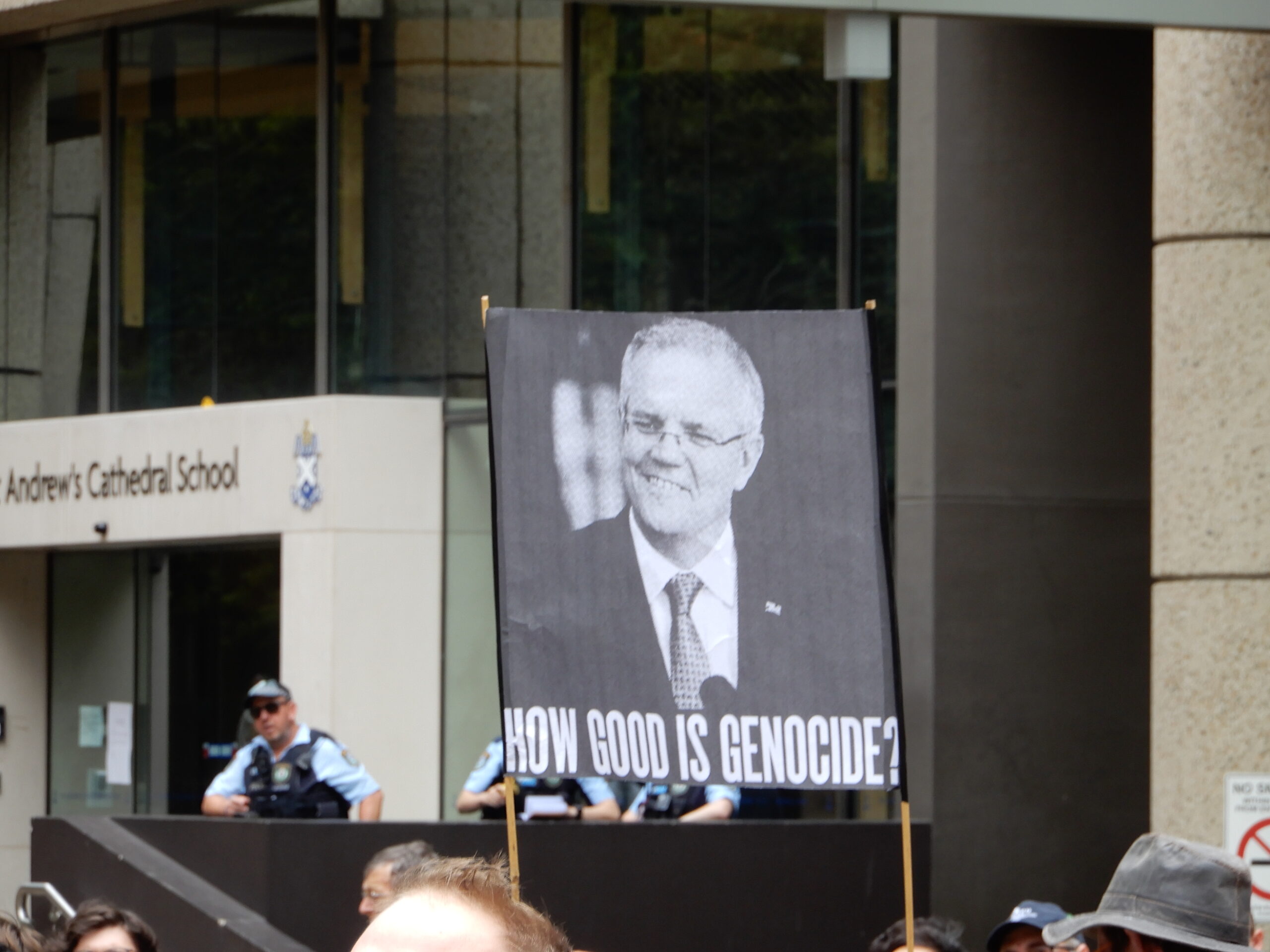

As protests against continuing First Nations deaths in custody began mobilising this month, prime minister Scott Morrison appeared on retrograde AM talkback radio stating that this nation “shouldn’t be importing the things that are happening overseas”.

The bulwark of conservative Australia was alluding to the Black Lives Matter uprisings that were sweeping the States, calling for an end to police brutality against black, brown and Indigenous peoples, which in turn, laid bare the travesty of law enforcement in this neck of the woods.

Morrison said that the country he represents has “issues in this space that we need to deal with, but the thing is we are dealing with it”. Although, the 437 First Nations deaths in custody since the royal commission tabled its recommendations in 1991 don’t indicate any meaningful dealings.

And nor do the countless pieces of footage capturing incidents of police violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that continue appearing on social media platforms. A man was bashed in SA this week. A teen was thrown to the ground face first in NSW three weeks back.

Indeed, the prime minister’s reaction to the Stop All Black Deaths in Custody rallies that were about to bring cities to a standstill was indicative that not only are the nation’s policing systems weighed down by the shackles of colonialism, but so too is the government.

“It is time for change”

Activist Bruce Shillingsworth told the 6 June protest crowd that literally covered Sydney’s Belmore Park and its surrounding streets that the reason he was present at the deaths in custody rally was for “his grandchildren and their children’s children”.

The Muruwari and Budjiti man asserted that those gathered were there to stand up against injustices around the world, those suffered by First Nations people locally and to call for a change to the systemic racism in the system.

Sparked by the killing of African American man George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, the current global focus on police brutality against people of colour has heightened the attention being given to the same racist violence perpetrated by Australian police.

As Melbourne Law School senior fellow Amanda Porter told Sydney Criminal Lawyers last week the NSW Police Force was established via the incorporation of various colonial policing bodies that were charged with quelling the Aboriginal resistance. And this confrontational stance still pervades.

“For 250 years now, my people have been suffering from the injustices,” Shillingsworth said over the loudspeaker. “We now stand and say enough is enough. So, stop. We are all humans.”

Mass incarceration by a foreign force

A coalition of Aboriginal and non-Indigenous law and social justice organisations put together a list of solid recommendations to guide federal, state and territory governments on how to prevent future black deaths in custody.

The civil society organisations include Change the Record, the Human Rights Law Centre and the Law Council of Australia.

The recommendations were made in response to a government announcement that it would simply be adding a justice component to the Closing the Gap framework, which seems to be a sure-fire way that nothing substantial will be achieved.

The first recommendation is to “end the mass imprisonment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”. At present 29 percent of the adult Australian prisoner population is made up of First Nations people, yet they only account for less than 3 percent of the overall populace.

An end to the incarceration of First Nations children, and a lifting of the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14 years old is the second recommendation.

Right now, 53 percent of incarcerated youths in this country are First Nations kids, while they only constitute 6 percent of the greater population between the ages of 10 to 17.

Making authorities accountable

Recommendation number three calls for the establishment of independent bodies to investigate deaths in custody and to provide police oversight.

As Indigenous Social Justice Association (ISJA) secretary Raul Bassi has long been at pains to point out the current system of sending Aboriginal custody deaths cases over to the Coroner’s Court usually results in no substantial recommendations being made, and certainly no criminal convictions.

While Gomeroi activist Gwenda Stanley maintains that First Nations people want investigations on their own terms.

“We want a reopening of all the black deaths in custody cases in Australia,” Stanley explained just before the mass rallies rocked the nation. “And we also want our own independent body that overlooks all the forensics to do with them.”

The sole NSW police oversight body is the underfunded LECC. It’s operational reach has been criticised as it still leaves much of the investigation of police up to police.

And any teeth the watchdog had were ripped out when Michael Adams was dropped as its head for going too hard on strip searches.

Decarceration now

The fourth call is to implement all the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Released in 1991, the investigation’s report included 339 recommendations, of which the majority have not been acted upon.

The 87th recommendation of the RCIADIC was that arrest should be “a sanction of last resort”, while the 92nd outlined that “imprisonment should be utilised only as a sanction of last resort”. However, the atrocious Indigenous incarceration figures reveal quite starkly that these have been ignored.

And the civil society coalition’s last suggestion is to “end the abuse, torture and solitary confinement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in police and prison cells through legislative safeguards and by urgently establishing independent oversight bodies to monitor” these institutions.

Towards an independent body

These recommendations though need to be reflected in the governing bodies that policing and correctional systems answer too, as the systemic racism inherent in this nation’s criminal justice systems is also present in its chambers of parliament.

NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge called out the bias in the NSW state government earlier this week, when he pointed out that rather than listening to the tens of thousands of voices demanding change, it prefers to focus on trifle matters.

But, breakthroughs do occur. Just a few days after Shoebridge rebuked the government, NSW parliament agreed to a Greens-moved motion to establish a cross-party parliamentary inquiry how deaths in custody are being investigated in this state.

In a statement, UTS Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning research director Larissa Behrendt recognised the move as “an important first step in a more transparent process” and establishing an independent investigative body.

The professor also acknowledged “the consistent frontline work done by First Nations families who have had family members die in custody who have been determined that other families not go through the same thing”.