Truth-Telling: Activist Stephen Langford on Facing Time Over Craft Gluing a Colonial Statue

The Black Lives Matter-Stop Black Deaths in Custody movement erupted in Sydney last June. Despite COVID lockdown restrictions only just being lifted, thousands took to the streets, as they challenged the tired and wearying official narrative around the British takeover of this continent.

It was in the midst of all this that veteran social justice activist Stephen Langford approached the Governor Lachlan Macquarie statue in Hyde Park North and pasted an A4 piece of paper to it. And to ensure the paper stuck, he used water-soluble craft glue.

If we can call this action a real crime, it was one that was captured on CCTV. And word was sent out over the NSW police radio network alerting officers that the hardened crime was on the loose, last seen cycling away from the CBD park in the direction of Surry Hills.

Law enforcement was able to apprehend Langford on College Street in the inner city suburb, only about 10 minutes from the park by bike. Officers arrested him, took him to the station, charged him, and sent him off to spend the night in the lockup, making sure he was strip searched beforehand.

A tale of two crimes

Langford appeared before the Downing Centre Local Court on 15 December 2020, so that Magistrate Vivien Swain could ascertain whether the facts against the alleged criminal could be established by the evidence. And indeed, it was found that it could be.

The son of an Austrian refugee is now facing hard time for the offence of destroying or damaging property, formally known as malicious damage. It falls under section 195 of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), where it’s described as the intentional or reckless destruction or damage of property.

These days the charge often referred to as malicious damage carries a maximum penalty of 5 years prison time if tried in the NSW District Court, but if it’s dealt with summarily in the Local Court – as in Langford’s case – it carries up to 2 years behind bars.

The maliciously damaging piece of paper detailed an 1816 directive the fifth governor of the colony of NSW gave to his military forces at the time.

Macquarie wrote, “All Aborigines from Sydney onwards are to be made prisoners of war and if they resist they are to be shot and their bodies to be hung from trees in the most conspicuous places near where they fall so as to strike fear into the hearts of surviving natives.”

This directive emboldened a British regiment to go out and perpetrate the April 1816 Appin Massacre, which saw at least 14 Dharawal and Gandangara people killed: some were shot, others were run off a cliff.

Macquarie subsequently assured his superiors that he’d greenlighted the atrocities.

Human rights defenders

In recognition of his campaigning on behalf of the Timorese people, Langford was awarded the Order of Timor in 2015.

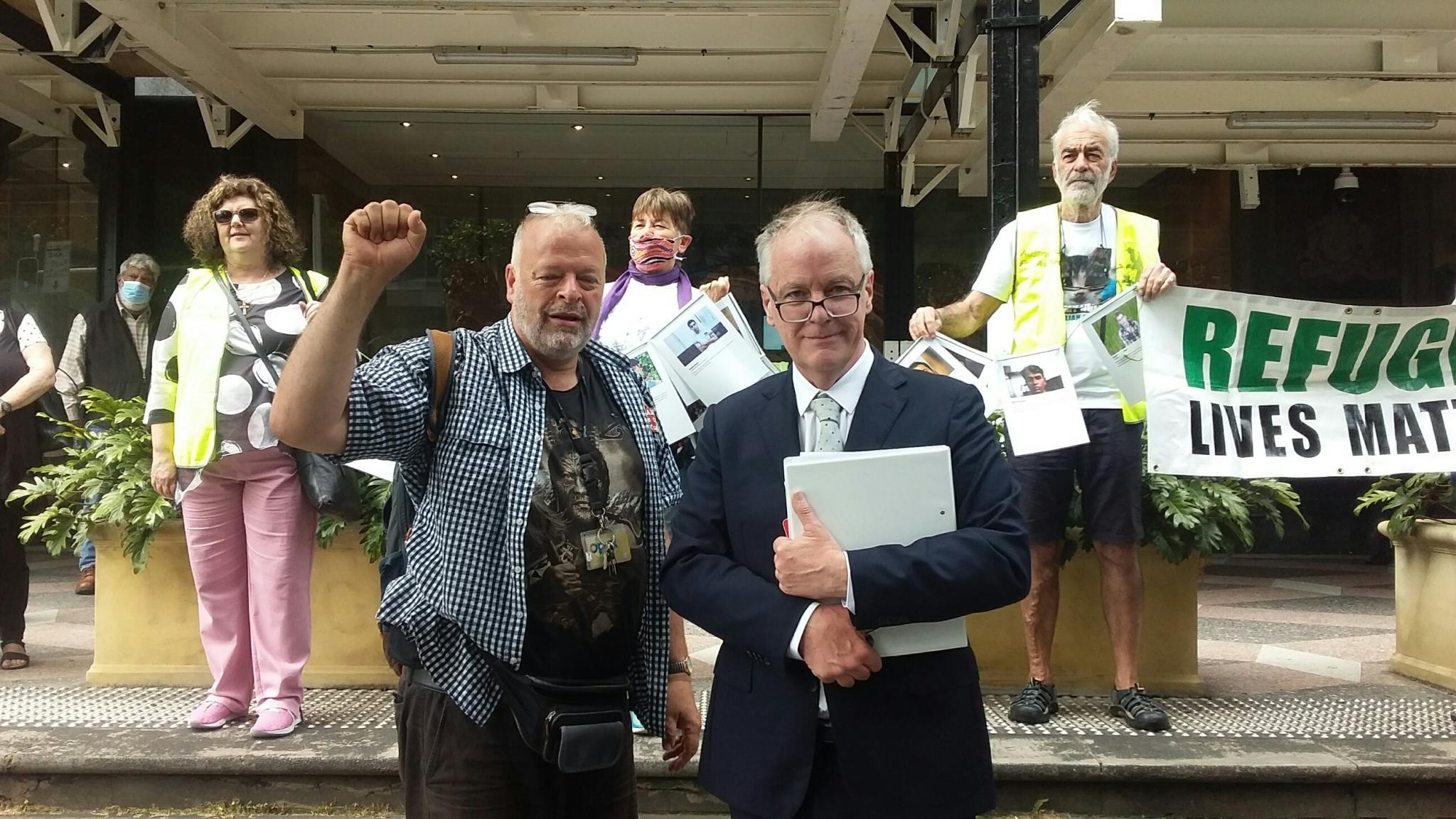

Lawyer Mark Davis last year expressed how his client had given his life to exposing the genocide in East Timor. And he added that he’d defend Langford any day of the week, which at present is next set to be on 25 May 2021.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Stephen Langford OT about facing prison for sticking up a sign that would have been washed away the next time it rained, as well as some of the other absurd aspects of his case, which certainly reveal the lengths authorities will go to in keeping the truth suppressed.

Firstly, Stephen, how would you describe the actions you took which have led to you facing potential prison time?

In sticking Macquarie’s words to the statue, I was telling more of the truth than the statue does, which is minimal.

What is stated on the statue is make believe: Macquarie was “a perfect gentleman, a Christian and a supreme legislator of the human heart”. It says bizarre things.

I don’t think there is anything wrong with damaging a statue. But I didn’t damage the property in any way.

Professor Jaky Troy wrote that there should be a way of making temporary changes to a statue to express an opinion. And I don’t see anything wrong with that. I don’t think the sky will fall in.

I really don’t think I’ll be sent to gaol. But if it comes to that, okay, let it rip.

You appeared before the magistrate on 15 December, so she could establish whether the facts against you could be proven.

Police prosecutor Amin Assaad suggested several times during the hearing that you’d superglued the sign to the statue, while you actually used craft glue.

And the magistrate found that there is enough evidence to establish the offence of malicious damage. What do you think about this finding?

It’s bizarre. If we’re arguing on that level, then anything is malicious damage. Putting a hat on the head of the statue would be malicious damage.

It seems she’s made a wrong judgement. But possibly the motivation for that is so that people do not feel free to stick notices to statues all over the place.

Although, that would actually be a really good way to open up a discussion in a civilised and contained manner.

If you want to stamp out discussion, dissent and protest the finding is right. But it’s a bad thing to do in a democracy.

She can’t say it’s legal or permissible. So, she had to say that something that obviously wasn’t malicious damage was malicious damage.

So, you pasted an A4 piece of paper on the Hyde Park statue of Governor Lachlan Macquarie, which detailed a 1816 directive that he gave to his troops.

The order involved taking any Aboriginal person the soldiers came across prisoner. But if that local resisted, they were to be shot and hung from a tree.

What was the purpose of placing this sign on the statue?

To do this sort of thing is a service. At the bottom of my notice it said, “Please do not remove. This is for public education”. It’s a form of political comment.

They’re his words that I pasted on the statue. I’m not saying he is a monster. He may have been. But that’s not what I have said. It’s just his words.

If we’re going to have a statue of Macquarie and not a statue of Pemulwuy or Barangaroo – if we’re going to have these colonial statues, they could at least tell a bit more of the truth.

If you broadcast something that’s erroneous, you would expect dissent. So, why don’t they expect dissent for having a misleading plaque?

Not that it’s necessarily wrong, but it is only part of the picture. We know it’s only part of the picture. And this statue was erected in 2013. It wasn’t 200 years ago.

So, it’s a fairly recently erected statue.

Yes. It’s aesthetically horrific. But, apart from that, it doesn’t tell the truth, or anything like the truth. It’s very partial in telling what he was about.

Your crime – if we can call it that – happened at the time that the Black Lives Matter movement was rising up in Sydney.

It also came just days after two other Sydneysiders were arrested for allegedly spray painting the Hyde Park Captain Cook statue with anti-colonial messaging.

Do you think this backdrop has caused an escalation in the manner in which the authorities are treating your case?

Yes. Definitely. That is what happened. It was only because the other statue incident had occurred that they came down on me like a tonne of bricks.

It came to light in the court that they were going from statue to statue with their cameras. From Queen Victoria to Lachlan Macquarie to another one.

They showed the footage in court. It showed me going to the statue and sticking the sign up.

But rather than charge you over the craft pasting incident and then let you go. NSW police actually placed you in Surry Hills lockup for the night, which included being strip searched.

What was the justification officers gave for locking you up over a bit of pasting?

It was because I had similar bits of paper in my bag. That’s not because I was going to do it again. There were many pieces of paper, some of them had messages about refugees and other things.

So, the implication was you might go craft pasting again?

Yes. That was their excuse. That I was on my way to do it again.

But in a way, I’m very grateful to them, because it was an education. It was the first time I had been in lockup. And the conditions in the lockup are abominable. I just had a taste of it. But people who are marginalised or poor will know what it’s about.

If you haven’t been there before it comes as a real surprise that it’s so much of a multiple human rights violation.

You’ve been convicted of a crime in the past, which had something to do with a 2016 incident and Malcolm Turnbull, could you tell us what happened there?

That was when refugee Omid Masoumali died in Brisbane, after setting fire to himself on Nauru. He was an Iranian gentleman. It was totally horrific.

It’s a terrible way to die. And it’s just a measure of the complete desperation that he’d reached – and that many people must have reached – to be willing to just end it all.

That is what Muhammad did quite recently at Villawood detention centre after being locked up for seven months. This is the level of torture that they’re putting people through.

So, what were you convicted of doing?

I spray painted RIP Omid on Turnbull’s wretched office steps in Edgecliff.

And lastly, your legal representation is Mark Davis: the esteemed Australian investigative journalist. He’s arguing a defence partially based on freedom of speech.

Stephen, how are you feeling about being represented by Davis?

His representation is fantastic. We’re really on the same page. As a broadcaster he was dedicated to telling the truth on East Timor. That’s why we admired him so much for what he was doing.

He told the truth about how the militias in East Timor weren’t rogue elements but were actually trained by the Indonesian army. Davis told the truth, and he knew it.

I know I’m being represented by someone who couldn’t do a better job. I’m not looking to get off on a technicality. I want this to advance society.

We’re stuck in telling ourselves this rubbish. We need the truth. And we need to wake up to truth and reality.

The truth in the region, the truth in the country and the truth of colonisation. And we do not need these statues saying, “History started here”.