The Number of Prison Inmates is Rising as Crimes Rates are Falling

Since the turn of the century, there’s been a dramatic surge in the number of women being incarcerated in Australia. Between 2000 and 2020, the amount of women in our nation’s prisons grew by 127 percent: up from 1,385 inmates to 3,144.

Although, this increase isn’t confined to women – who make up about 8 percent of the overall adult prison population in this country – as a similar spike can be seen in the number of their male counterparts being locked up.

In June 2000, there were 21,714 male and female adult prisoners in Australian correctional facilities, while in June last year, there were 41,060 adults on the inside. This accounts for an 89 percent rise in adult inmates over the past two decades, which can’t simply be put down to population growth.

The adult imprisonment rate in 2000 was 148 inmates per 100,000 adult persons. Last year, that rate was at 202 inmates per 100,000 adults. And if you go back further, you find in 1990, the rate was 112 prisoners per 100,000 Australian adults.

But no one is suggesting that these figures can be put down to more men and women turning to a life of crime. In fact, over the same timeframe, crime rates have been dropping exponentially.

Indeed, rather than a marked rise in criminality, what’s been fuelling the ever-increasing Australian prisoner population are tougher laws and policies, accompanied by enhanced policing.

And this is kind of lucky as over 20 new adult prisons have been built nationwide since 2000, and they need to be filled.

Declining crime

As former NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) director Dr Don Weatherburn has explained in the past, in terms of crime rates in this state, “between 1982 and 2000, practically everything went up”, while “from 2000, most, but not everything, went down”.

In his 2016 Rack ’em, Pack ’em and Stack ’em paper, Weatherburn set out that nationally since 2001, robbery had dropped by 66 percent, burglary was down by 67 percent and motor vehicle theft had declined by 71 percent.

The few crime categories that had increased were drug trafficking, sexual assault and fraud.

According to Weatherburn, in the 1970s and 80s prisons were used sparingly. But, between 1974 and 1989, there was a steep climb in violent and property crime, which subsequently led to growing public concerns and politicians responded with a suite of “tough law and order policies”.

“In the period up to 2000, it was a combination of increasing crime, and tough law and order policies,” Dr Weatherburn told Sydney Criminal Lawyers in 2017. “In the period after 2000, it was just the tougher law and order policies.”

And a recently released BOCSAR report outlines that over the three decades from 1990, the rates of most major property and violent crime categories in NSW dropped or remained stable. That’s except for a marked rise in sexual assault and other sexual offences.

More beds for fresh inmates

However, over the last two decades, NSW has seen something of a prison boom, which has taken off over the last five years in particular.

In June 2016, the Baird government announced the $3.8 billion Prison Bed Capacity Program: a four year prison expansion project that would see an extra 7,000 prison beds in this state.

At the time of the announcement, there were 12,550 adults incarcerated in NSW, meaning the increase in bed capacity would accommodate a 55 percent rise in the prisoner population.

The funding was used to reopen Berrima gaol and expand both Wellington and Cessnock prisons. It was also used to finance the repurposing of a former Lidcombe youth facility into an adult remand centre, as well as pay for the construction of the Illawarra Reintegration Centre.

Although the largest prison in the country, the recently opened Clarence Correctional Centre, wasn’t factored into the funding program. This joint public and private venture has been run by Serco since it opened outside of Grafton last June, and it provides an extra 1,700 beds.

But the Berejiklian government hasn’t yet finished. In December, it came to light that the Sydney suburb of Camellia will be the site of a new 1,000 bed adult prison. And this facility is part of a fresh Corrective Services NSW plan to increase prison capacity by a further 5,000 beds by 2025.

The production of inmates

There are a number of reasons why the NSW prisoner population has been growing at the same time that crime rates are on the decline.

Chief amongst them is the ongoing toughening of bail laws, which has led to a situation where these days, a third of prisoners are on remand, meaning they’re yet to be found guilty or they’ve been convicted and are awaiting sentencing.

Further reasons for the rise in incarceration rates in NSW are a broadening of the range of criminal offences, truth in sentencing laws, higher arrest rates, enhanced police powers, more targeted policing, a move towards proactive policing and an ever-growing number of NSW police officers.

In an article she wrote last December, UNSW professor of criminology Eileen Baldry pointed to another factor that’s keeping prisons full, and that is incarceration doesn’t rehabilitate. Rather it produces illegal activity, which sees more than half those sentenced to prison return after release.

Systemic racism

While everyone is affected by this tendency to lock up more citizens, those most affected are First Nations communities. While they constitute less than 3 percent of the overall population of this continent, they account for 29 percent of the adult prisoner population.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are subject to enhanced policing. They’re more likely to be arrested and imprisoned over minor offences. And they’re more likely to be denied bail. These circumstances have led them to be the most incarcerated people on Earth.

And this situation also leads to the ongoing crisis of custodial deaths, which has seen over 470 First Nations deaths in the custody of either police or corrections since 1991.

Towards abolition

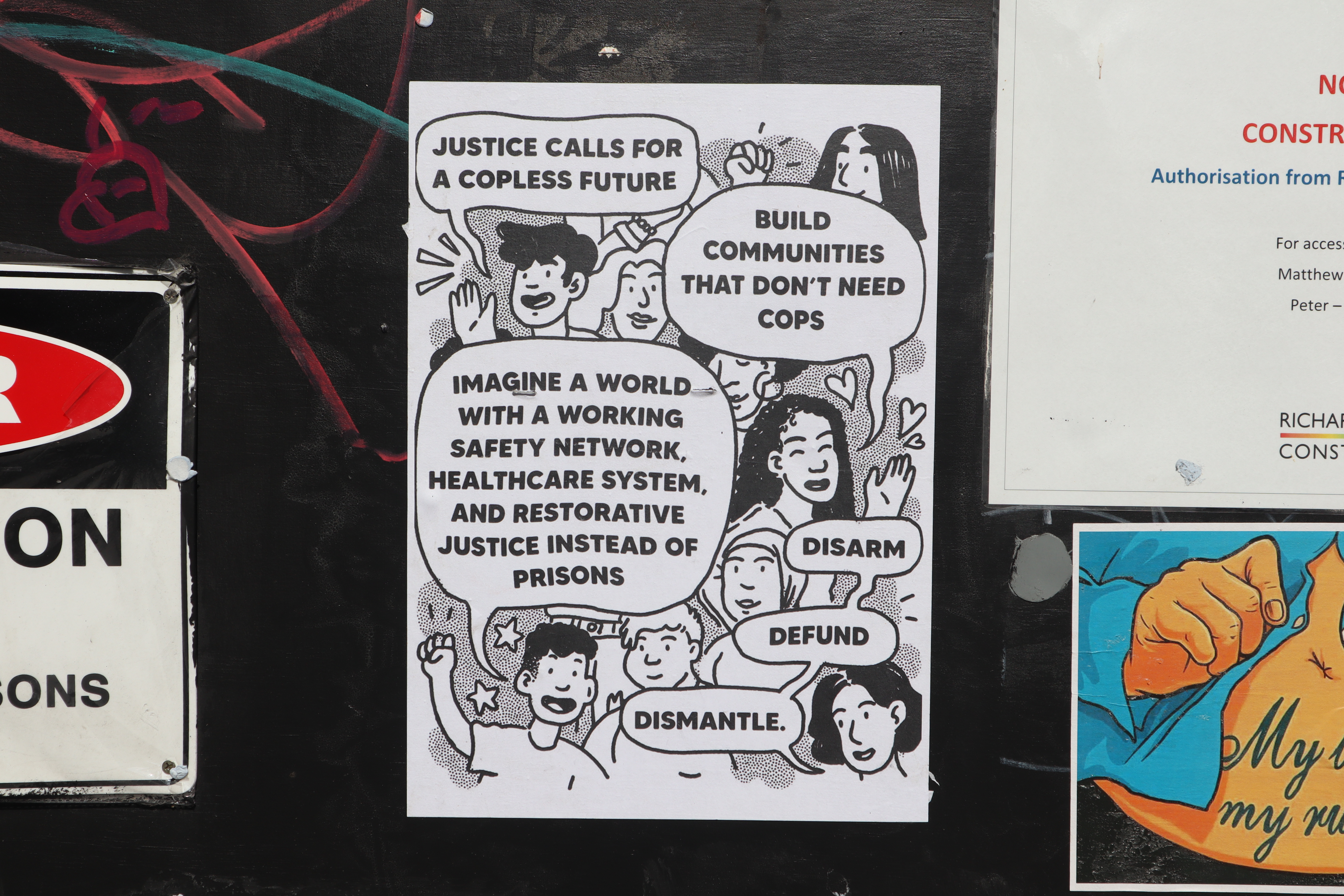

Over the last 12 months, the global rise in the Black Lives Matter movement has put the campaigns for prison abolition and defunding the police before mainstream audiences.

So, while these causes are perhaps not yet embraced by Middle Australia, it has certainly become aware of these ideas.

The prison abolitionist movement has its roots in the 1970s Black rights movement in the United States. And it advocates for a gradual decarceration of correctional facilities, along with a move towards dealing with crime within the community.

Rather than punitive measures, abolition points towards healing practices and dealing with the root causes of crime.

As Flat Out chair Amanda George explained in 2017, “structural inequalities, like gender, racism, lack of access to education, lack of housing… are intricately involved in who ends up in prison.” So, rather than investing in more, money should be directed into social services that address underlying issues.