High Court Finds that Indefinite Detention Is Lawful, to Government’s Delight

The majority of the High Court ruled on Wednesday that the indefinite detention of refugees, asylum seekers and long-term residents who are regarded as ‘unlawful non-citizens’ can lawfully be held in immigration detention for an indefinite period of time under authority of the executive.

Four High Court Justices – Susan Kiefel, Stephen Gageler, Patrick Keane and Simon Steward – upheld an appeal brought by the federal government against a September 2020 Federal Court ruling – known as AJL20 – which found that constitutional limits don’t permit the executive to do this.

The case put by human rights lawyer Alison Battisson in AJL20 involved the ongoing detention of a then 29-year-old Syrian man, following the cancellation of his visa in 2014 on character grounds. Having migrated in 1996, the government hadn’t deported him due to non-refoulement obligations.

This decision was rumoured to have led to the release of around two-thirds of the Medevac refugees from detention, although this was never substantiated. And in May, the government made amendments to the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (the Act) to patch up the legal loophole.

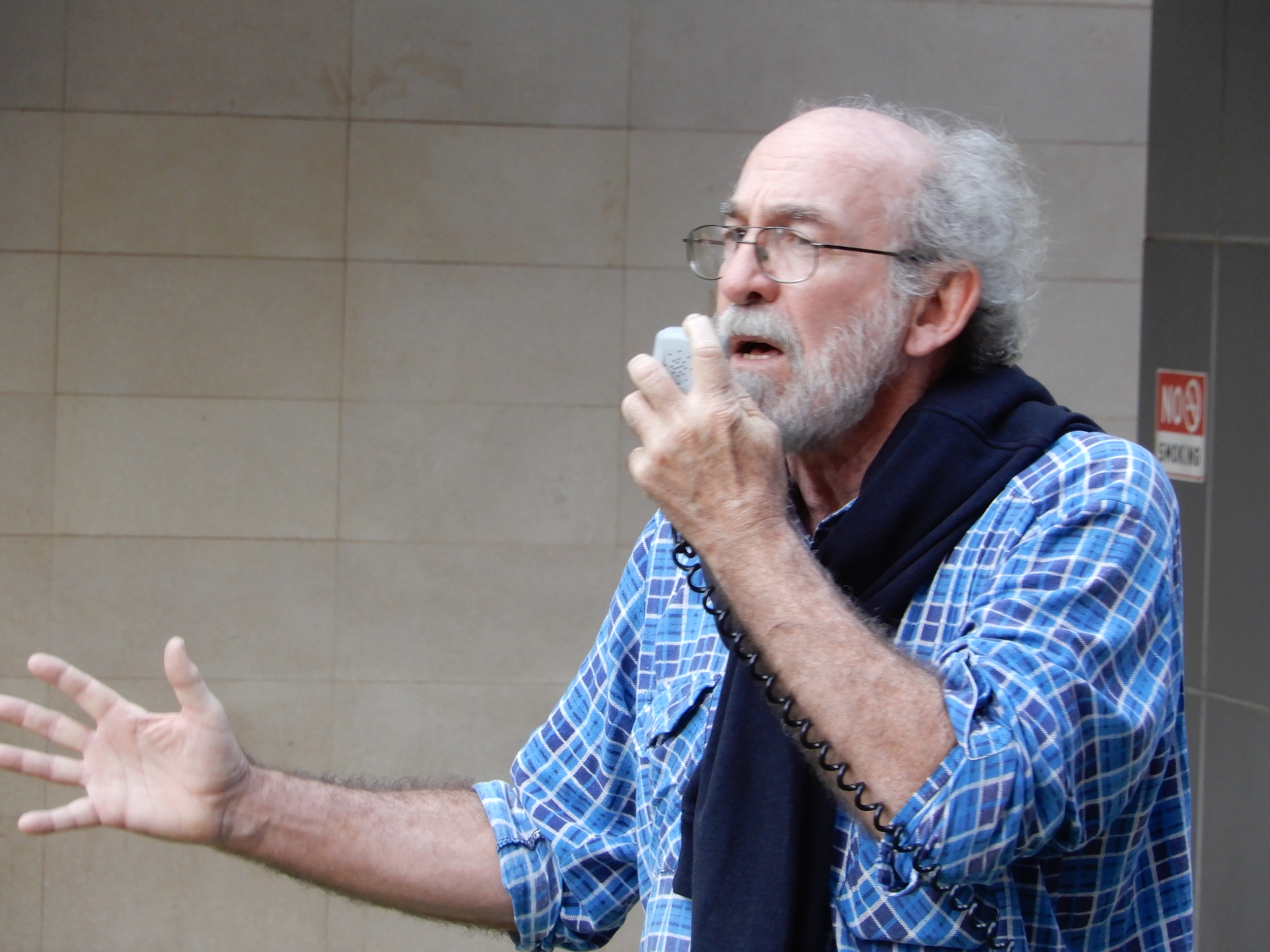

Leading refugee rights advocate Ian Rintoul maintains that the combination of the court decision and its legislative pre-empting by the Morrison government, has placed refugees and asylum seekers beyond the scope of laws that pertain to citizens and made the executive “a law unto itself”.

A decades-old position

“It entrenches indefinite detention as part of the Migration Act, and, in that respect, as part of Australian law,” said Rintoul, spokesperson for the Refugee Action Coalition (RAC). “It was a very sharply divided decision, but, nevertheless, the majority has entrenched that position for now.”

“They made a distinction that under the Act people can be held indefinitely, but it’s in administrative detention not punitive,” he told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “The courts have now found that this distinction is law in Australia.”

Rintoul advises that this is not the first time the High Court has ruled that our nation’s migration law permits the indefinite detention of unlawful non-citizens, who aren’t being provided a visa and nor can they be returned to their countries of origin due to the risk of irreparable harm.

In 2004’s Al-Kateb versus Godwin, the High Court found that the indefinite detention of a stateless person was lawful, when Palestinian man Ahmed Al-Kateb wasn’t provided a protection visa, and no other country would accept him. However, Al-Kateb was eventually granted a permanent visa.

“It makes a mockery of the rule of law when there is one law for citizens and another applies to asylum seekers and refugees,” Rintoul continued. And he added that the court should try explaining to long-term detainees how being locked up in administrative detention isn’t punitive.

The findings of the court

The majority of the High Court found that section 189(1) of the Act authorises and requires the executive to detain unlawful non-citizens, meaning those who are not citizens of Australia and have no valid visa permitting them to stay here.

While section 196(1) of the Act requires that an unlawful non-citizen must be held in immigration detention until they are removed to another country, or they’re granted a visa to stay here.

In AJL20, Federal Court Justice Mordecai Bromberg set out that 198(6) of the Act required an unlawful non-citizen be deported “as soon as reasonably practicable” and that section 197C requires this be done regardless of the nation’s non-refoulement obligations.

Contained in the 1951 Refugee Convention, the principle of non-refoulement prohibits the return of asylum seekers to the country from which they fled if it entails a genuine risk of irreparable harm. And as Australia is a party to this agreement, it couldn’t send the Syrian man to his country of origin.

The Federal Court further found that under these circumstances the executive didn’t have the power under the Constitution to indefinitely detain an individual.

However, the High Court pointed to the precedent set in the 2003 Federal Court case NAES v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, which found that the requirement to detain unlawful non-citizens isn’t altered by the removal as soon as reasonably practicable clause.

Further section 51(xix) of the Australian Constitution permits a law for the detention of non-citizens. And even though chapter 3 of the Constitution makes involuntary detention the “province of the courts”, there is an exception when it comes to the administrative detention of non-citizens.

Clarifying ongoing detention

In response to the AJL20 ruling, the Morrison government last month passed the Migration Amendment (Clarifying International Obligations for Removal) Bill 2021. It effectively clarified in law that the government can continue holding unlawful non-citizens without any time limit.

National Justice Project director George Newhouse explained that not only did the government pass laws to ensure it isn’t required to deport an unlawful non-citizen to irreparable harm, but it also gave the minister the power to withdraw an earlier protection status finding.

“The minister is now creating a power to reverse a decision that a person needs protection from harm, discrimination or death,” the human rights lawyer said after the passing of the bill. “Essentially, the minister now has the power to revoke refugee status.”

A growing number of lifers

The ruling in AJL20 resulted in the Syrian man being released into the community without a visa. And as yet there has been no move to place the long-term Australian resident back in immigration detention following the High Court overturning the argument that led to his release.

The Morrison government is currently detaining around 100 unlawful noncitizens within its immigration detention facilities who’ve been there for over five years. And with these new developments, Rintoul asserts that their numbers are only set to grow.

“So, we’ve got the Migration Act – a special area of law – which is now able to impose life sentences on individuals because of character assessments that are unable to be challenged or they’re refugees not being released and held indefinitely,” Rintoul concluded.

“We will see an increasing number of people in detention who are simply condemned to indefinite detention with no avenues of legal review.”