Indigenous Deaths in Custody Continue Unabated

A New South Wales family is still waiting for meaningful answers about the final moments of Frank ‘Gud’ Coleman, and why he died alone last week in a Sydney prison cell.

Mr Coleman is the seventh Indigenous Australian to die in prison since March. His family is now desperately seeking answers from New South Wales Corrective Services. The only piece of information they have is that he was found ‘unresponsive’ in his cell.

Adding to their heartbreak is the fact they hadn’t seen him for more than a year because of Covid-19 restrictions.

Family members say that as far as they were aware ,‘Gud’ Coleman was in good health. They are demanding both an autopsy and coronial inquest as soon as possible.

Indigenous deaths in custody continue unabated

At least 478 Indigenous people have died in custody since the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Despite its final report which made more than 300 life-saving recommendations for reducing deaths, it remains gathering dust in a filing cabinet somewhere in the halls of power.

In May this year the Federal Government promised that it would speed up its reporting on Aboriginal deaths in custody following criticism that it was taking too long to produce information that could be critical for policy reform.

The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) will now report every six months, which is considered a big step forward. Until a few years ago the AIC was publishing reports based on a two-year timeframe which meant that there could be a period of as much as three and a half years between a death and it being reported.

Inadequate information and no accountability

A lack of reliable information and data was a distinct theme of the 1991 Royal Commission because without proper investigations and timely information there can be no accountability. Nor can authorities pinpoint shortcomings of the system and make much-needed improvements.

Earlier this year, New South Wales Correctional Services came under fire for not releasing details about Indigenous deaths in custody.

To its shame, an Aboriginal woman who took her own life in March at Long Bay Correctional Centre was able to do so because she was being held in a cell with ‘hanging points’ after an assessment identified her as ‘not at high risk’ of self-harm. In 1991.

One of the Royal Commission’s recommendations was to remove these hanging points. But thirty years on, some prison cells continue to have them.

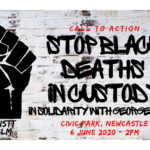

It is remarkable that in 2021, on the back of the global “Black Lives Matter” riots sparked by the death of George Floyd, which struck a deep chord with the Australian public, Indigenous Australians are still dying at unacceptably high rates in custody.

Figures reported recently point to the fact that since the Royal Commission, the entire situation has actually deteriorated. The number of Indigenous people imprisoned has increased 100 per cent in the past three decades.

Indigenous Australians are six times more likely to die in police custody and 10 times more likely to die in prison custody than non-Indigenous people, because of the disproportionate rates of incarceration, amongst other factors such systemic racism in the justice system, including police brutality.

Amongst youth it is even worse. Half of all children in detention nationally are Indigenous. In the Northern Territory, the figure is more than 90 per cent.

Will Australia ever reach true reconciliation?

In 2007, then Prime Minister Kevin Nudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations looked like a positive step towards reconciliation, which was the final recommendation of the Royal Commission report which stated that: “reconciliation between the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities in Australia must be achieved if community division, discord and injustice to Aboriginal people are to be avoided”.

But the apology has provided little more than false hope. And the most frustrating part of all of this is that the social appetite is ripe for change — for better outcomes for indigenous people across the board.

Over the past two years during the Covid epidemic our politicians have shown that they can make swift decisions and take action in a crisis, and yet they continue to drag their heels on issues that matter a great deal to the majority of Australians, such as the high rates of Aboriginal deaths in custody, soaring domestic violence, poverty and homelessness as well as political accountability and climate change.

In the meantime, despite getting a few runs on the board with its response to the global epidemic, Covid-19 continues to be the ultimate distraction for our Federal Politicians, and provides the ultimate excuse to allow these other issues to remain stagnant.