“Moving Too Slow”: Bruce Shillingsworth on the COVID Response in First Nations Towns

Broken Hill-based Maari Ma Aboriginal Health Corporation wrote to the federal government in March 2020 to warn about the potential for COVID-19 to wreak havoc within First Nations communities in north western NSW and the need for emergency plans to be put in place.

But nothing was done.

Fast forward to mid-August this year, and the much-more virulent Delta strain of the COVID-19 virus had managed to spread its way out from the weeks-long lockdown in Greater Sydney to those vulnerable Indigenous communities out west.

Wilcannia is one of the towns where COVID has taken hold amongst the Aboriginal community, with infection rates now higher than “areas of concern” in Sydney. And by the end of last week, over 1,000 Indigenous people had contracted the virus in the west of the state.

Maari Ma has since written to the PM, warning that there’s now an “unfolding humanitarian crisis” occurring amongst First Nations communities in the region, and despite the NSW premier’s assurances that things are under control, it’s “chaotic” and “mistakes and problems are mounting”.

Settler colonial neglect

Since the pandemic commenced, it’s been understood that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are particularly vulnerable to the virus as the harms of the ongoing colonial project has left them with poor health outcomes and a lack of adequate medical services.

With this understanding, the federal health department categorised these communities as a priority group for the vaccine rollout. However, despite this, the vaccination rate amongst First Nations communities is at 20 percent below the national rate, and in some areas, it’s decidedly worse.

Now with the federal and NSW Liberal Nationals governments rushing to open at 70 and 80 percent adult vaccination rates, the grave fear is that this will occur when many of these vulnerable communities are nowhere near the inoculation targets supposed to provide adequate protection.

And just this week, the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW (AHMRC) told a parliamentary inquiry that they haven’t had a meeting with state health authorities at any point during the 18 months of the pandemic: not on vaccines, prevention measures or opening up.

Grassroots support

Food security resulting from a COVID-19 outbreak amongst north and north western NSW First Nations communities was an issue Maari Ma raised with the federal government in March last year.

Yet, these warnings weren’t heeded. So, the First Nations Emergency Management Committee (FNEMC) has been set up to raise funds and get food supplies out to these vulnerable communities who are locked down in their homes with dwindling provisions.

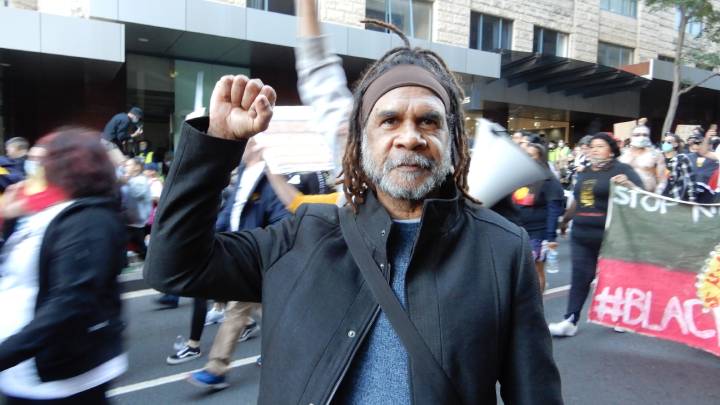

Muruwari and Budjiti man Bruce Shillingsworth is one of those organising the FNEMC. Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to the prominent water for rivers activist about what’s transpiring in western NSW, the slow drip vaccine rollout in these communities and why the FNEMC is needed.

Firstly, despite weeks of lockdown in Greater Sydney, the COVID-19 virus has spread to First Nations communities in north western NSW.

Wilcannia, Bourke, Enngonia and Brewarrina: that’s where they’ve got the cases.

Bruce, you’ve been in contact with these communities regularly throughout the crisis, as you have a son living in Bourke and a daughter in Brewarrina. So, what’s happening out west?

A lot of the communities are struggling, because they’re not getting support from the services, especially the service deliveries in those communities and government. They’re not assisting those communities very well.

I’ve been speaking to those communities, as I have family there. They’re crying out for food and a lot of them have been fined by police.

There is a heavy presence of police in those communities. The people are getting charged and fined with $1,000 or $5,000 fines, just for going to the shop to get groceries.

How prepared were these communities for the onset of the virus?

There is no education around the vaccine rollout. There is no education to tell them about the extra police powers.

They’ve got the army out there, especially in Bourke, Brewarrina and Wilcannia. Why are they there?

So, how is the vaccine situation?

It’s slow. Some of it’s because of hesitancy amongst First Nations communities. Some don’t want the jab, because they don’t know what it’s all about.

All this is new. There needs to be an education program to let them know what’s really going on, and what the need for the jab is.

The COVID pandemic commenced in March last year. It’s always been understood that these First Nations communities have a heightened vulnerability to an outbreak.

Why weren’t greater protections put in place, especially since the Delta variant commenced spreading rapidly around Greater Sydney over a month before it made its way out west?

If you look at March 2020, when COVID came about, these government organisations and councils were supposed to put in plans for this situation.

Apparently, there are no plans. I haven’t seen any. It’s a failure to our mob out there in the bush. There is no coordination at all between the services.

I know they’ve set up the LEMCs (local emergency management committees) in those communities. But they’re slow to react because of the lack of support from the government.

They’ve been sitting around the table now for 18 months, but there doesn’t seem to be any plans in place.

The government is now talking about opening up at 70 and 80 percent adult vaccination rates.

In your understanding, does that equate to those rates being met throughout the state? Are there concerns around how this plan will affect these communities?

If you look at the wider community outside of our First Nations communities, they can have 70 or 80 percent, but that does not mean that you’ll have 70 or 80 percent in our First Nations communities.

They are so far out there. Their numbers are not being counted properly. First Nations communities are behind the ball with getting the vaccine.

So, it will be a disaster if we are to open up for communities up there where 80 or 90 percent are First Nations people, and many haven’t got their vax yet. If you look at the percentages, it’s very low.

They need to get the vax out there and give people the jab who want it. They’re just moving too slow for me. It’s too slow for our community.

And lastly, Bruce, you’re involved in running the First Nations Emergency Management Committee. What’s that all about?

We set up the First Nations Emergency Management Committee to counteract the local LEMCs. We’ve been having a problem with the LEMCs in those communities, like Bourke and Brewarrina, because they’re not servicing our communities.

The First Nations Emergency Management Committee is organising food drops and support for our people. We believe that First Nations people have an obligation to support their neighbouring nations in those areas.

We have come up against obstacles like the police stopping us from working with our grassroots people in Bourke. We’ve been denied the ability to help as a committee. We set this up to counteract that.

As an example, we organised food to go to Enngonia. But the Bourke LEMC and the police stopped our food getting through. They took it back to Bourke. So, the mob out at Enngonia didn’t get any.

The same thing has been happening in Brewarrina. We had trucks going in there. The police are telling the drivers not to come to Brewarrina with the food.

So, we’ve been having those problems, and that is why we set up the FNEMC to put strategies in place to support our grassroots people and make sure that they’re being serviced.