China is Perpetrating Genocide Against the Uyghurs, Rules Tribunal

The Uyghur Tribunal released its final judgment on Thursday into whether the People’s Republic of China “has been and is attacking with the intent of destroying a part, or parts”, of the Uyghur and other Turkic minority populations living under its rule in the far western province of Xinjiang.

The independent tribunal was conceived when World Uyghur Congress president Dolkun Isa requested Sir Geoffrey Nice QC – who led the genocide prosecution against Slobodan Milosevic – create a body to investigate the “possible genocide” against the Uyghur people in June last year.

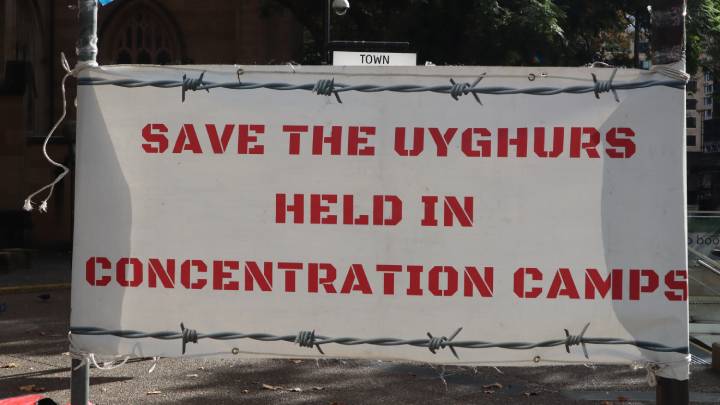

Isa told Sydney Criminal Lawyers in March 2018 that the Chinese Communist Party had commenced running internment camps in Xinjiang in April the year prior, and these were incarcerating up to a million Uyghurs without charge or trial for the purposes of political indoctrination.

The tribunal relied on the Genocide Convention, which defines the crime of genocide as any of five acts perpetrated against a national, ethnic, racial or religious group with intent to destroy it, in whole or in part.

The five prohibited acts are killing members of the group, subjecting them to serious bodily or mental harm, inflicting conditions calculated to cause physical destruction, the prevention of births, or forced child removals.

And the tribunal has found that genocide is occurring, and that documents reveal that Chinese president Xi Jinping and other top officials “bear primary responsibility” for acts that include building an “extensive network of detention and penal institutions” to incarcerate Uyghurs without cause.

The gravest of crimes

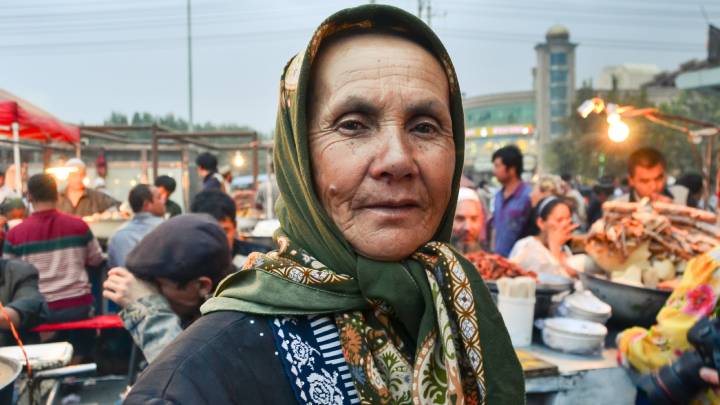

In its summing up, the Uyghur Tribunal found it “incontrovertible that the Uyghurs are a distinct ethnic, racial and religious group and as such can be defined positively and as a protected group for the purposes of the Genocide Convention,” of which China is a party to.

The court was satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that the PRC has committed torture, crimes against humanity and genocide against the Uyghurs.

In terms of crimes against humanity, these have consisted of transfer and deportation, imprisonment and other severe deprivations of liberty, torture, rape and other sexual violence, forced sterilisations, persecution and enforced disappearances.

On the finding of genocide, the tribunal considered killings, serious harms, deliberately inflicting conditions and the forcible removal of children. And while the members found that all of these have occurred, they couldn’t conclude that they were intended to cause the destruction of the group.

Some of the acts that comprised these crimes included the destruction of places of worship, all-pervasive surveillance of the Indigenous peoples, the razing of homes, forced labour, deprivation of medicine and nutrition whilst in detention, and the removal of thousands of children.

But in terms of “the imposition of measures to prevent births” – which included removal of wombs, forced abortions and insertions of contraceptive devices – the tribunal ruled that the PRC had “intended to destroy a significant part of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang”, and so “has committed genocide”.

A brief history of oppression

The Chinese Communist Party commenced its takeover of the Xinjiang region – known to Uyghurs as East Turkestan – in 1949, which was around the same time that Chairman Mao Zedong’s troops began their invasion of Tibet.

In 1954, the CCP established the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. Still operating today, this is a state-owned economic and paramilitary organisation, which is charged with administering and developing the province, as well as securing the border region internally and externally.

Since that time, Beijing has been running a transmigration program into Xinjiang, encouraging Han Chinese people to move to the remote western region with an aim of them becoming the majority population.

And the CCP’s rule has grown increasingly oppressive over its time in operation. This has been markedly so over the last decade, which has seen increasing prohibitions on cultural practices, incarceration, mass surveillance, as well as a spike in Uyghurs fleeing overseas to seek asylum.

As Isa explained prior to the onset of the camps in March 2017, CCP secretary Chen Quanguo was placed in control of Xinjiang in mid-2016, and he set about implementing a range of draconian measures he was notorious for having used upon the Tibetans whilst in charge of their homelands.

Today, both the Uyghur and Tibetan populations are some of the most surveilled and policed people on the planet.

Doves shouldn’t dismiss atrocities

The tribunal members made clear that in their deliberations they were aware that much of the evidence presented came from those “predisposed against the PRC”, and they further acknowledged that Beijing does a lot to meet the vast needs of “the world’s largest national population”.

Indeed, the tribunal’s findings come as nations, like the United States and Australia, are running a concerted political campaign, aimed at provoking China into war or at least staging a prolonged cold war with the East Asian giant.

And along with regional issues such as Taiwan and Hong Kong, the repression of the Uyghurs is being raised as a primary reason for warring on China.

This citing of the Xinjiang situation by those with China in their sights has led political commentators opposed to war to downplay the atrocities perpetrated against the Uyghurs as a means to combat the rising drums of war.

However, as leading US political commentator Noam Chomsky has pointed out, condemning Beijing’s human rights abuses does not lead to them posing a threat to foreign nations, in the same way that “US support for Israel’s terrorist war against… Gaza” poses no threat to Beijing.

As Isa outlined in 2018, at that point the international community was paying no attention to the atrocities in his homelands even though up to a million of his people had reportedly been imprisoned in the internment camps without due process.

And it might be thought with the tribunal’s finding of genocide, that the international community may seek to bring an end to these atrocities via diplomatic means, such as the imposition of sanctions and other means.

Collective pain validated

The Australian Uyghur Association released a statement soon after the Uyghur Tribunal delivered its finding of genocide on 9 December.

The local organisation asserts that given the outcome of the tribunal, the Australian government now holds a legal responsibility to act upon the serious risk of genocide. And it hopes that Canberra will acknowledge the tribunal’s finding and act to prevent further atrocities.

“For a community that has for so long been denied accountability – or even recognition – today, has made us feel seen, and has validated our collective pain,” said Australian Uyghur Association secretary Bahtiyar Bora.

“The world can no longer plead innocence – there can now only be bystanders, or those actively fighting for the survival of my people.”