UK Offers US Assange on a Platter, as PM Washes His Hands Sealing the Australian’s Fate

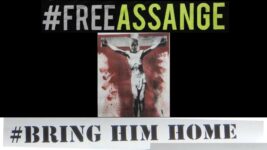

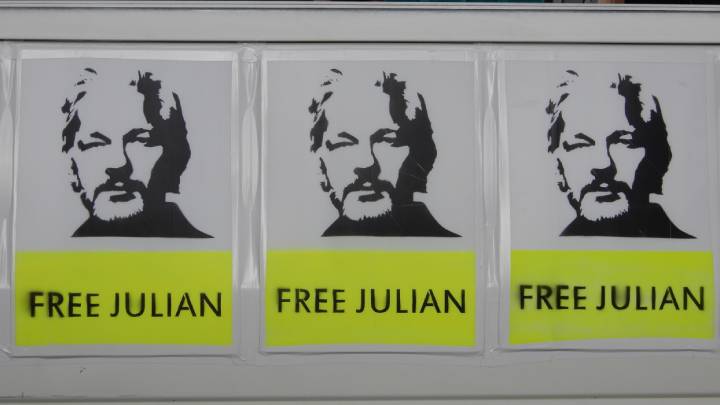

The UK High Court overturned the Westminster Magistrates’ Court decision not to extradite Julian Assange to the United States last Friday, as the Biden administration continues to seek to prosecute the Australian journalist in relation to a swag of charges laid under former president Donald Trump.

District Judge Vanessa Baraitser ruled against extraditing the Wikileaks founder on 4 January, based on his mental health and Washington’s inability to ensure his conditions of confinement wouldn’t lead to his suicide. But she also upheld the substantial US case for his release into its custody.

The bare bones of the White House’s pursuit of Assange is due to his having published hundreds of thousands of top secret US diplomatic and military files leaked by former US Army soldier Chelsea Manning. Although ongoing subsequent leaks seem to have strengthened Washington’s resolve.

In the 10 December findings, two High Court lord justices outlined they were satisfied with the assurances the US had given Britain in relation to the conditions and punishments the Australian would face in prison, despite Washington having reserved the right to change its mind in the future.

The case has now been remitted to the lower court with the direction for the original judge to send the case to UK home secretary Priti Patel to make the final decision on extradition.

However, Julian’s legal team has vowed to raise a final appeal of the recent decision to the UK Supreme Court.

“A travesty of justice”

Following the Baraitser decision, the US offered the UK four assurances last February in regard to the treatment Assange would receive under its custody, which the High Court has accepted as “solemn undertakings offered by one government to another”.

The first assurance is that the US would not impose “special administrative measures” or SAMS upon Assange “pretrial or post-conviction”. These measures involve prolonged solitary confinement, which the UN considers torture, as well as extremely limited contact with the outside world.

Washington has assured it will not imprison Assange in Colorado’s Florence ADX facility: a supermax prison for offenders who’ve committed the most heinous crimes.

And the US has guaranteed against these measures, as they’d usually be expected under such circumstances.

Further assurances included the Australian citizen would be given adequate mental health treatment and be able to serve any forthcoming prison sentence in this country.

Yet, Assange’s legal team raised two similar extradition cases where such promises have been broken in the past.

While Amnesty International’s Europe director Nils Muižnieks pointed out on Friday that these assurances are flawed, as the US has reserved the right to apply the extreme conditions at the ADX facility if Assange “commits any future act which renders him liable to such conditions of detention”.

Extra-legalities

The legalities around the attempt to extradite Assange to the US have been under question ever since UK authorities dragged the publisher out of London’s Ecuadorian embassy in April 2019, in connection with the Trump administration’s 2017 extradition request.

This move involved Washington reaching out across international borders to arrest Assange by proxy over charges laid under its own domestic spying laws for crimes he allegedly committed on foreign soil via a request based on a treaty that prevents extradition on political grounds.

A second superseding indictment was released by the US in June last year. And it sees the multi-awarding-winning journalist facing 17 counts of espionage and one of computer hacking, which together carry a maximum penalty of 175 years behind bars.

However, in June this year, a key witness for the case set out within the indictment, Icelandic national Sigurdur Thordarson, admitted in the press that he’d provided the FBI with false evidence that incriminated Assange as a part of a deal to avoid his having to serve time in a US gaol.

Whilst Yahoo News reported in September that US officials had revealed that under the guidance of then CIA director Mike Pompeo, the Trump administration had considered kidnapping Assange from the embassy, and that then president Trump had even flagged a potential assassination.

And it came to light in mid-2020, that US intelligence agencies had been spying on the Australian publisher in the Ecuadorian embassy since mid-2017, via cameras installed by Spanish security firm Undercover Global SL, which included listening in to conversations he’d had with his lawyers.

An attack on press freedoms

The broader implications of Assange’s case over publishing multiple caches of classified documents, including the Afghan and Iraqi war logs, are that it sets a precedent whereby the US and other nations may reach across borders to prosecute foreigners for publishing inconvenient truths.

Assange didn’t commit the crimes that Washington would rather he hadn’t exposed, but instead he received documents leaked by Manning and published them, which is exactly what journalists are expected to do explained veteran political reporter Laurie Oakes during the 2010 Walkley Awards.

Following the release of the decision on Friday, Reporters Without Borders secretary general Christophe Deloire condemned the High Court ruling, outlining that it has “dangerous implications for the future of journalism and press freedom around the world”.

Pontius prime minister

As Baraitser’s decision reflected, Assange’s mental health has dramatically deteriorated due to his initial seven-year confinement in the embassy, followed by the last two and half years spent – mainly on remand – in London’s Belmarsh Prison, often in a state of prolonged solitary confinement.

Assange’s fiancé and mother of his two young children, Stella Moris revealed on Sunday that Julian suffered a mini-stroke whilst the High Court appeal hearings were being held in October.

Independent MP Andrew Wilkie and Greens leader Adam Bandt, along with a number of other Australian MPs, have called on PM Scott Morrison to intervene on behalf of the journalist to ask our nation’s closest allies to bring the “politically motivated” extradition and prosecution to an end.

The Department of Foreign Affairs responded to the Guardian over the weekend, outlining that our government’s position is it “will continue to respect the UK legal process”, adding that it’s up to the Wikileaks founder to challenge the decision, as “Australia is not a party to the case”.

And as for his part, Morrison continues to make no formal response to Assange’s case, not following the High Court decision, nor at any other time since Julian was taken into UK custody, except for an initial pledge not to provide his country’s own citizen with “any special treatment”.

The PM’s ongoing silence over such a vital matter – at a time when his Coalition government is pursuing a number of politically motivated prosecutions designed to punish those who have exposed its own secrets – might be considered as tacit approval of the persecution of an Australian son.