Six Years on, Still No Justice for David Dungay Jnr, Says Dunghutti Activist Paul Silva

The footage of five Long Bay prison guards holding David Dungay Jnr facedown in the prone position on a bed, as he screams out that he can’t breathe multiple times, is not only hard to watch, but it begs why it didn’t receive the same outrage as the killing of George Floyd did in the US.

Indeed, it took the murder of Floyd by Minneapolis police officers to spark widespread recognition around Dungay’s death in this country, which speaks volumes about how deeply the denial of the plight of First Nations people is buried in the broader middle Australian psyche.

The unbridled aggression that the initial six guards set upon Dungay with, just moments before they pushed the life out of him, was unleashed because the 26-year-old Dunghutti man refused to stop eating a packet of biscuits, which a nurse had raised concerns about because he was a diabetic.

Today, the 29th of December 2021, marks six years since David Dungay Junior’s life was taken from him. And an inquest, widespread campaigning, petitions, and calls for NSW authorities to reinvestigate the case have all resulted in no justice being served.

Yet, this is the norm in the Australian setting when it comes to the dispossessed and systematically oppressed First Peoples of this continent.

A nation’s shame

But the mass wave of Black Lives Matter that erupted across the globe following Floyd’s death did raise awareness to the ongoing injustices that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to be subjected to here, especially in regard to custodial deaths.

With this came 100,000 signatures calling on the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions and SafeWork NSW to reinvestigate Dungay’s killing. And NSW criminal barrister Phillip Boulten SC issued detailed advice outlining the potential for charges to be laid. But all this was to no avail.

In the broader context, this year has seen fifteen Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths take place in the custody of either corrections or law enforcement, while it also marked 30 years since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody handed down its final report.

No justice was served in the October trial of a WA police officer over the 2019 killing of Yamatji Woman JC in the town of Geraldton, despite the shooting clearly being uncalled for.

Whilst the NT officer who killed Warlpiri teen Kumanjayi Walker, Zachary Rolfe, has been trying to argue in the High Court that it was all in good faith.

Forging change

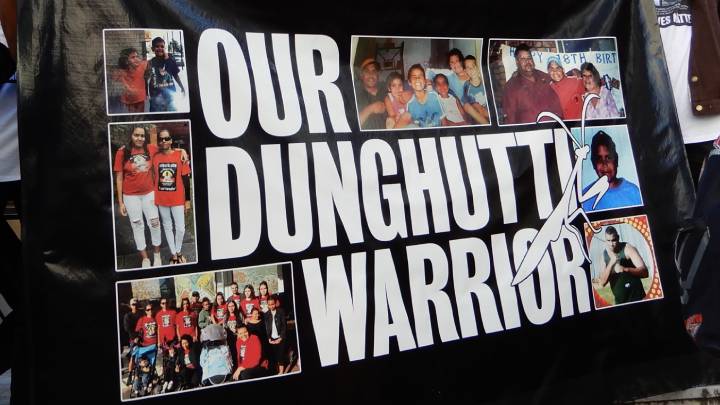

Paul Silva was still young when he lost his uncle, David Dungay Junior. Six years on, the Dunghutti man is now a seasoned rights activist, who has been one of the leading voices in the campaign for Justice for David Dungay Junior.

The path that Silva has walked has been one that was birthed in pain. And today, despite the many setbacks he, and indeed the rest of his family have faced, Paul continues to advocate for those who killed his uncle to be brought to account, and further, for an end to First Nations custodial deaths.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Paul Silva about how he’s marking the passing of his uncle today, the prejudice and brutality that First Nations people continue to face in the last days of 2021, and how the Dungays are taking the fight to the United Nations, backed by legal heavyweights.

Paul, your uncle David Dungay Junior was killed by five Long Bay prison guards on 29 December 2015, after he’d refused to follow an order to stop eating a packet of biscuits.

No one has ever been brought to justice. Although following the inquest, Corrective Services NSW did admit the organisation had failed in multiple ways.

Wednesday marks six years since your uncle lost his life. What will you be doing to remember David on the day?

I’ll be attending his grave, sitting there and spending time with him.

Many years ago, we did organise protests at Long Bay correctional facility, where it took place. Although, it’s around Christmas, so we haven’t gotten around to organising one this year.

But we are calling on the wider community to wear something red, take a photo and to hashtag “Justice for David Dungay Junior”.

This is to keep his name out and about and to raise awareness to Aboriginal deaths in custody.

Since your uncle’s death, you’ve been campaigning for those who killed him to be brought to justice.

Over that time, you initially struggled to bring attention to the issue, and then you received statewide and international recognition.

But despite the growing wider community support, you’ve also been given multiple refusals to take matters further from different agencies.

What would you say you’ve learnt about how the system works in this country?

Throughout this movement, I’ve been exposed to how the system fails First Nations people.

I’ve been involved with Aboriginal deaths in custody for six years now, and I’ve seen how First Nations people aren’t treated with dignity or respect on their own lands that they walk on.

There is no justice or accountability when it comes to brutality and death against First Nations people.

Last April saw the 30th anniversary of the handing down of the report produced by the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. It made 339 recommendations, most of which have yet to be implemented.

By the time the anniversary came about, there had already been five First Nations custodial deaths this year. By the end of 2021, there have been 15 such deaths in the custody of authorities.

What are your thoughts on what’s transpired this year?

It’s appalling. That amount of deaths in the custody of Corrective Services or police while there was an inquiry being heard.

It shows that those in government are not recognising these events and making the drastic changes needed to prevent them.

They simply don’t care because it is First Nations people losing their lives, and not white people, or any other nationalities.

The next stage in the campaign to see justice for David Dungay, will see your aunt, Leetona Dungay, taking the case to the UN Human Rights Committee with barristers Geoffrey Robertson and Jennifer Robinson providing representation.

This was announced mid-year. How are the preparations for mounting the case going?

The preparations are going well. We’ve requested to have the case heard in the UN court. We are hoping for a good outcome in that regard.

We shouldn’t have to take it outside of the Australian government, because it has enough power to hold Corrective Services and police to account for these murders and these events.

For our family to have to take it outside of this government is a big step. And the main focus is to shame the Australian government over how it handles deaths in custody and brutality against First Nations people.

I now believe justice may never come for David. That’s the sad reality of Australia, and how the justice system was built against First Nations people.

The justice system was not built for us. It was simply built against us: to make us fail, end up in custody and have this lifestyle we have.

Aboriginal deaths in custody have occurred on this continent since the British invaded. Despite the detailed way forward set out by the Royal Commission, at least 485 First Nations custodial deaths have occurred since 1991.

How should things be developing from here?

There could be more community engagement from government and authorities. The bad cops should be held accountable. They should be reassuring the public that systematic racism will not continue.

Many families have reached out to Scott Morrison to talk about these issues, but he’s declined.

We are taking the routes to make changes within the community, as well as with the relationships with police and community members. But they’re not stepping up in regard to deaths in custody or police brutality.

As I see it, they simply condone it.

You mention Scott Morrison. How would you say the current prime minister has addressed the plight of First Nations people?

Over his time in office, he hasn’t really dealt with the issues of First Nations people. He has been requested to sit down with family members and talk about these issues, but he simply shrugs it off.

We are all for it. But he needs to come to the table, talk about it and make changes. By not doing this, it just shows what sort of human being he really is.

And lastly, you’ve had the position you hold today as a prominent First Nations activist thrust upon you by tragedy. You’ve continued to campaign for the past six years despite a number of setbacks along the way.

Paul, what are your plans from here in this regard?

My plans are to continue to raise awareness about Aboriginal deaths in custody, and to try to put a stop to them.

The more awareness that’s raised, the more police and Corrective Services know that the community understands what’s going on.

The main thing I’d like to see going into the future is for the Director of Public Prosecutions to investigate deaths in custody, and for SafeWork NSW to conduct independent investigations alongside the coronial process.

There are a lot of things our family and others have asked to be implemented. But nothing was implemented following the 1991 Royal Commission.

I don’t think they’re ever going to fix this issue. Like I said, First Nations people die, and the government, police and corrections don’t care.

It’s just that whole cycle going back to when it was first invaded.