WA Poisoned First Nations With Agent Orange: An Interview With Ngikalikarra’s Dr Magali McDuffie

The US military perpetrated Operation Ranch Hand, which involved spraying toxic herbicides over vast tracts of land in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia between 1961 and 1971. This form of chemical warfare not only destroyed forest cover, but it killed numerous locals then and for generations.

The most notorious chemical weapon/herbicide used by the US is known as Agent Orange.

A lesser-known tale of a government purposefully using the two herbicides – 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D – that together constitute Agent Orange happened in the Kimberley region of northern Western Australia, roughly over a ten year period between 1975 and 1985.

The WA Agricultural Protection Board (APB) utilised the use of these chemicals, which by that time were well known to be heavily toxic, to eradicate introduced weeds in the region that were causing problems for farmers in terms of the effects these plants were having upon cattle and sheep.

In order to carry out the weed eradication program, the APB employed local First Nations people to spray the highly toxic herbicides across the region, using completely dodgy equipment, without explaining what the chemicals were or how extremely dangerous exposure to them could be.

Indeed, the program might be described as a subtle form of chemical warfare.

An eradication program

The APB was well aware that during the early 1970s, there was an excess of Aboriginal labour in the region, as new laws established in the late 1960s guaranteed equal wages for Indigenous pastoral workers in the Kimberley, and due to this, the white farmers sacked all their First Nations labourers.

But those same farmers were having trouble with weeds that were messing with their livestock, so the APB established a massive weed eradication program in the region. And to do this, it began importing barrels of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D, as these chemicals were known to be extremely effective.

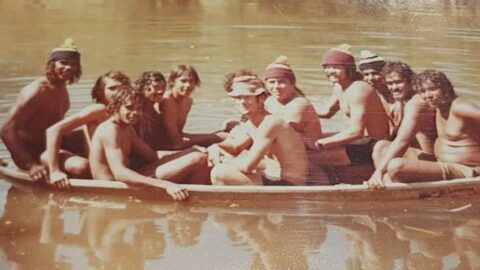

The Western Australian government agency then hired hundreds of unemployed First Nations men to form work groups who were sent out to spray these highly toxic chemicals. The APB though, neglected to warn them about the weed killer or supply them with any protective gear.

And as the soon-to-be released documentary On Australian Shores: Survivor Stories tells it, these men believed there was nothing to worry about to the point that they would mix the chemicals by hand, work with clothes drenched in them and weren’t concerned with washing away any residue.

From the mouths of survivors

Produced and directed by Ngikalikarra Media, On Australian Shores tells the story of the wanton neglect of the WA Agricultural Protection Board via a series of interviews with survivors, their family members that have outlived them, and current generations still affected by the poisoning.

Premiering from June onwards on both NITV and SBS online platforms, the documentary is a harrowing story of a large number of Aboriginal men and their families, who were knowingly and unwittingly poisoned by government in order to enhance the profits of the agricultural industry.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Ngikalikarra Media co-producer, director and editor Dr Magali McDuffie about how despite numerous inquiries and reports the overwhelming majority of victims remain uncompensated, while the WA government continues to deny any of it ever happened.

Cultural warning this interview contains names and images of people who have passed away.

During the 1970s and 1980s in the Kimberley region of WA, the state government’s Agricultural Protection Board ran a weed eradication project along the Fitzroy River with the aim of making it more hospitable to cattle and sheep farming projects in the area.

The APB imported two different forms of chemicals in barrels from overseas, which, when mixed together, form Agent Orange. And the teams of people employed to carry out this work were majority First Nations peoples.

Most of the Australian community is well aware that Agent Orange was used as a chemical weapon by US forces against the people of Vietnam during the prolonged war in that Southeast Asian nation. This use of the chemical weapon constituted multiple war crimes.

Dr McDuffie, how did it come to be that this chemical weapon was being distributed for an ongoing period in the Western Australian outback to kill off bothersome weeds?

During the Second World War, a lot of research was carried out on chemical herbicides, as a continuation of the “scorched earth” war practices that had been used since the dawn of times – depriving the enemy of food and cover.

At the same time, farmers in Britain and the United States were battling insects and weeds destroying their crops, and DDT had already proven to be a formidable weapon against insects since 1939.

2,4,5-T (2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid), and 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) were part of the first generation of “miracle” weed killers, introduced as early as 1945, against broad-leaved weeds.

These highly toxic herbicides were found to be particularly effective for weed control, even at low dosages.

In Australia, most of the weeds threatening agricultural and pastoral production had been introduced, and those new herbicides proved to be very effective against them.

As a consequence, they were used in many places across Australia from the late 1940s onwards. In Western Australia, they were used by the Forests Department, the Kings Park Board, and the Agriculture Protection Board.

The fact remains that 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D mixed together were principally used as a military weapon of mass destruction – WOMD, Agent Orange – during the Vietnam War, with the health impacts of the TCDD dioxin contained in 2,4,5-T being already apparent at the time.

The WA government’s APS understood what it was doing in terms of the chemicals it was using and the fact it was offering First Nations people paid work to go out and distribute them via spraying them in the region without warning these people of what they were using and the dangers of it.

How was the government able to get away with withholding this key information about the operation? And what does it say to you in terms of the attitude the authorities had towards the Aboriginal people involved?

With the use of herbicides by the APB in the Kimberley region, there are two things to remember:

The first is that no precautions were taken in spite of the department being aware of the toxicity of some of those herbicides.

Pesticide and herbicide storage and spraying protocols had been put in place at the start of the 1980s.

They were clear and detailed, listing a list of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) workers should wear and how the liquids should be stored and handled.

Why was this never communicated to the workers? They all say they never received any training, and barely any PPE. And when they did get overalls, those were thoroughly inadequate for the Kimberley climate, and would get soaked anyway.

Now without even mentioning Agent Orange, the negligent practice of the APB is what we are questioning in this documentary.

How were those young men allowed to go out for days and sometimes weeks into the bush, spraying herbicides in shorts and thongs, mixing them up themselves by hand, and being told that these were harmless?

The second important point is that an ABC Four Corners report in 2013 investigated the import of drums of 2,4,5-T, which had been damaged in a fire in Singapore.

They tracked the drums to a facility in Kwinana, Perth, but were unable to track them to the Kimberley.

Scientists at the time said that the analysis of the residues in those drums showed the dioxin toxicity contained in the product – TCDD – was up to 200 times higher than normal due to the drums having been heavily damaged in the fire.

The 1982 Harper inquiry reported that it was highly likely that it was those drums that made it to the Kimberley and that were used by the APB workers.

The other questions asked in the documentary pertain to the knowledge that government officials had about the toxicity of these herbicides.

Concerns regarding the effects of these herbicides on human health were raised in the press as early as the 1950s.

The United States banned the use of 2,4,5-T on all food crops except rice in 1970. The New Zealand press reported on the adverse effects of 2,4,5-T on unborn babies and farmers’ animals and crops in 1972.

Numerous reports about high rates of miscarriages after the spraying of 2,4,5-T over forests in Oregon were republished in Australian newspapers. The then health minister, Mr Hunt, was questioned at length about this in Parliament.

Several government enquiries about the dangers of 2,4,5-T took place from 1979 onwards.

A committee of inquiry set up in 1982 under the NSW Wran Government, by the then agriculture minister Jack Hallam was highly criticised in the press in 1982, when it decided to keep meetings confidential, and refused to allow access to scientific reports and submissions.

The European Commission itself called for a partial ban on 2,4,5-T in 1982.

Given the depth of information, which was freely available and circulated in the mainstream media at the time, why weren’t precautions taken to ensure the health and lives of the APB workers were not put at risk during that time?

We have to remember that Kimberley pastoral stations got rid of most of their Aboriginal workforce at the end of the 1960s, into the early 1970s, when equal wages legislation was passed.

This means that a lot of Aboriginal people went to live in the towns, and many were unemployed and trying to find work.

The APB weed spraying campaign came about at the right time for those young men desperately seeking work to support their families.

It would be easy to surmise that this was indeed a known fact, that people in charge knew most applicants to the job would be Aboriginal, and that the matter would be “out of sight, out of mind” in such a remote part of the world.

This was not just one case of catastrophic negligence, but protracted, repeated, and concerted non-actions on the part of a government department for more than ten years, and then a total disregard for the families impacted by this negligence up until today.

The main boss of the APB in Derby, Western Australia during that period was Carl Drysdale, who appears in the 2012 7:30 Report, “Pinjarra Man”, and previously campaigned for the compensation of ex-APB workers. He declined to be interviewed for this documentary.

The documentary On Australian Shores: Survivor Stories involves detailed accounts from people who took part in the weed eradication programs and their family members.

It explores how those involved treated the Agent Orange in a manner that showed they had absolutely no understanding that it could cause them harm, let alone how toxic it was.

It also touches upon the detrimental outcomes the chemicals had upon the people involved.

In your understanding, what were the harmful outcomes that the use of Agent Orange in such a careless manner resulted in? How widespread were these damaging results? And are they still taking their toll today?

The stories in this film speak for themselves, and we know there are many more out there: the APB workforce numbered about 300 men in total in the Kimberley.

The worst of them happened when a group of young men in their thirties all passed away suddenly, mostly from apparent heart attacks, in the 1980s.

All of them were part of the APB crew. Many of those who did not die in their thirties developed cancers later on in life, and untreatable, painful skin diseases. One man, Richard Greatorex, became blind.

Their wives and partners suffered countless miscarriages or had to abort their unborn babies due to catastrophic malformations. Many could not have any children at all.

Ex-APB employees also suffered from renal failure, headaches, chest pains, internal bleeding, and other unexplained ailments.

The toll has been immense intergenerationally as well. Those workers’ children and grandchildren were born with malformations and disabilities, and skin conditions.

When Cyril Hunter passed away from a heart attack in the 1980s, his son Nigel was only two. Nigel himself died at the age of 32 in 2013, after suffering from a rare cancer.

As his mum Suzanne explains in the film, she used to wash his dad’s clothes in the same washing machine, so he was exposed to the toxins as a young toddler.

Lena Buckle’s grandson passed away from an unexplained seizure in his 20s as well.

In the first government inquiry in 2002, Dr Harper recommended in his report that families should be compensated, as these men and their families had suffered many ailments stemming from their hazardous occupation.

Dr Harper was of the view that the workers had been exposed to high levels of dioxin, and that they had not benefited from the levels of hygiene that should have been put in place.

The government opened another inquiry a year later to try and establish scientific proof. The Armstrong report, published in 2003, concluded that only people with cancer would get compensation, as it was not conclusive that their other ailments had been caused through their involvement with the APB.

If this is the case, why did the government then hold on to the organs of the workers who had passed away?

The families of Cyril Hunter and Terry Hunter were told that their organs had been kept in a facility in Perth for further examination.

To this day, their remains have never been returned to the families. We were told they were buried minus their vital organs like their spleen, liver, kidneys, heart and brains.

Following the Armstrong report, a Kimberley nurse support service was established at the Derby Aboriginal Health service, and a clinical toxicologist was sent from Perth to provide education and advice to local doctors as to the sort of ailments they might see.

The question is, why was all this put in place if the government believed that people’s deaths had nothing to do with their work with the APB?

As Paddy Watson so rightly says in the film, “I am 69 years of age, and I look around and think, where are all my mates? Where does this happen anywhere, in any gang, that the immediate crew gets wiped dead?”

Ngikalikarra Media produced the documentary, which is a business partnership run by you and your partner Dr Alexander Hayes. What drew you both to the story? And what sort of toll would you say it had on you in telling it?

I have been privileged to work in the Kimberley since 2007. First as a filmmaker and later on as a PhD researcher.

One of the first people I met then, senior Nyikina Elder Lucy Marshall AM became a very close friend and family member.

Over the years of working with her, and her sisters – Professor Anne Poelina of the Nulungu Research Institute of Notre Dame University, and Nykina Senior Elder Jeannie Warbie – I learned of the tragic stories of their family members.

Their son, brother, grandson and nephew, who had died too young because of the APB’s negligence.

Through working with other communities throughout the region, I understood how widespread this tragedy had been, affecting hundreds of families in the Kimberley.

I met Alexander Hayes who was a researcher and data administrator at the Australian National University (ANU) in 2014.

He’d been working prior with Aboriginal communities in Western Australia. He came to work with me in the Kimberley.

Jeannie Warbie gave us the name “Ngikalikarra” – it means “you’ve got to listen” in Nyikina.

This is the founding principle of all the work we do. We listen to people’s stories, on Country, and make sure that those stories are heard, and importantly, that they are also returned to the people themselves: they are our producers and are in control of their story.

This is part of a wider Kalara framework, which I developed throughout the course of my PhD research with Nyikina women. Those stories don’t belong to us. They belong to the people. We are just facilitators, in a sense.

When we moved to Perth, we found out that we lived only a few blocks away from Lucy’s son, Eugene McMahon. Eugene was very much wanting to see the APB story told, having lost his older brother Cyril, and his nephew Nigel.

He put us in touch with Colin McCumstie, who had grown up in Derby and witnessed so many of his former schoolmates pass away.

Colin, his family and the McCasker family generously agreed to fund us for two trips to the Kimberley to record those stories with Eugene.

Alex started working full-time on this project, and everything fell into place rather quickly. It seemed that the story was meant to be told then.

Film is a wonderful medium, you know, documentary in particular. I always see it as a process, not just an outcome or a final product.

For people to relate their stories, experiences, grief, and trauma, when they feel no one has listened to them before, is quite cathartic.

Alexander interviewed Trevor Lockyer a few months before he died of cancer. Trevor told him that he wanted to do the interview for his family, so his children and family would know about what happened to him, and why he died.

I saw Trevor in Derby, on his deathbed, the day before he died of cancer. I told him that we were editing the film, and that his story would be seen by many people. He almost could not speak, but he smiled, and I will never forget that.

It is all part of the power of documentary to be heard, to be listened to, to tell your own story in your own words for posterity.

For us, the whole endeavour had an historical dimension as well. These stories will not die, even after the people have died. They will forever be a reminder of the negligent practices of a government department, which caused so much heartache and trauma in a whole community.

Filming the families’ stories was very sad, as their grief and trauma is palpable. Most of these stories are still raw, like they happened yesterday. It is not something they can put behind them, it has affected their whole life.

Some stories were all the more heartbreaking that we knew the people we were interviewing were dying, like Trevor Lockyer, and Vincent Angus.

It took me a long time to edit the film. I wanted to do justice to all interviewees, and include them all in the film, as well as for them to come together to collectively tell the bigger story in most of its aspects.

The investigative part, which had been well-covered by the ABC reports, took a backseat to the people’s stories themselves. The project basically took three years from start to finish.

I was concentrating on my role as an editor and making sure I was telling the story in the right way throughout it all, but when I reached the final edit point, and Alex and I sat down together to watch the entire film, we both broke down crying.

We were quite overwhelmed by the magnitude of the project we had taken on and completed.

I still cry now whenever I see it. I think primarily of Lucy Marshall, who started it all, who received the Order of Australia Medal for her ongoing fight for the victims of Agent Orange in the Kimberley, and who sadly passed away last year without ever seeing any resolution to it all.

My only consolation is that she got to see the rough cut of the film before she passed away. She knew the film was coming out. And I hope it does her family’s story justice, and all the other families’ stories. That is all we wanted.

We know there are more people out there who were not interviewed and have similar stories. We did our best with the time and means that we had.

We sincerely hope that this documentary resolves finally in a class action, for all the victims to be compensated, regardless of the ailments they have suffered.

As Nyikina leader Robert Watson says, so rightly at the end of the film, “Ultimately, humans made decisions. They made the decision to bring these dangerous chemicals to our doorstep. And this needs to be investigated”.

Putting this Agent Orange weed eradication program into the context of the broader settler colonial project that has been taking place on this continent over the last 250 years, what would you say it tells us about this country currently known as Australia and its treatment of the sovereign peoples of the land?

This is something that I have researched a lot and much of this is written up in my PhD thesis. The history of the Kimberley region is one of terrible violence and oppression against Aboriginal people.

Numerous massacres occurred in the early years of frontier conflicts, massacres that are still depicted in today’s oral histories.

In the 1870s, Aboriginal people from all over the region were kidnapped to work on pearling luggers. From the 1880s, they were rounded up to work as slaves on the pastoral stations.

The use of free Aboriginal labour went on until the end of the 1960s, with people working for little more than tea, flour, sugar, and blankets rations, until the equal wages legislation was passed, and most of them were thrown out of the stations to congregate in the towns, with little or no work opportunities.

Those who did not live on the stations were rounded up on the missions to be “civilised”. The whole basis of “civilisation” was to conquer the land and make what was seen as unproductive territories productive.

Everything was seen through an economic lens. Development at all costs was the priority, and still is today, with little consultation as to what Aboriginal people want to see happen on their Country.

When invasive weeds started to derail the production of wool, and to poison the cattle, the reaction was swift: use the strongest herbicides possible to fix the situation so this would not impact the local economy.

This occurred at the cost of many people’s lives, health, and well-being, and the legacy of this inequity remains ongoing today.

And lastly, Dr McDuffie, On Australian Shores: Survivor Stories focuses on the accounts of the workers and their families, who fell victim to a government-sanctioned operation that displayed blatant disregard for their lives.

It’s not the first telling of the story. Indeed, researchers, politicians, and journalists have worked tirelessly upon what happened in the Kimberley with the weed eradication project in the past.

So, what do you hope your telling of the story achieves? And what sort of measures has the government taken in response to these atrocities, and further, what actions should it be taking?

For us, it was important that the story be told by the people themselves, the survivors, and the victims’ families.

We are not investigative journalists – although we carried out a lot of research for this documentary.

The ABC investigations on the 7:30 Report in 2012, and Four Corners in 2013, had done an excellent job of presenting the background issues, government enquiries, scientific reports and investigations into alleged 2,4,5-T dioxin contamination from a fire-damaged batch imported into Australia, as well as touching on Lucy’s family’s story, and the death of her son and grandson from their exposure to the chemicals.

The fact remains, despite these research investigations nothing has ever been resolved for the 42 families we interviewed and the countless number of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people right through Australia who have been unduly, and, as Professor Anne Poelina reiterates, affected in a “genocide” against them and their communities.

It is important to note that at the time we started the project, only eight people had ever received compensation, out of the hundreds of workers and countless thousands who were affected and ongoing in proximity to these poisoned workers.

It is a huge story in the Kimberley. Everyone knows about the APB. Everyone still talks about it, and the effects of the chemicals are still felt and seen today in the younger generations.

Most families felt that their voices had not been heard, that investigations had led nowhere, and that they were going to die without answers, without any recognition of their lifelong plight, and most of all, without an apology from the government.

Our effort is part of a long line of attempts by many people to bring this story to some sort of resolution.

Former WA Greens MLC member for mining and pastoral region Robin Chapple championed the rights of ex-APB workers for over twenty years in parliament, bringing about two formal enquiries into the matter.

Former agriculture minister Kim Chance also expressed his support for compensation for the workers and their families.

The ABC took up the story in a 7:30 Report and a Four Corners episode. Many news articles were written over the years.

I guess that with our film, we wanted to put faces to the tragedy: people talking to other people about something that should never have happened to them in their lifetime, so the fight can be resolved, so justice can be actioned, so human remains can be returned to Country and so the families and communities affected can get closure.