The Sun Has Quietly Set on the NT Intervention, or Has It?

Considering the Howard government deployed ADF troops to remote Aboriginal communities in June 2007 to implement the NT Intervention, the brief 17 June post on a federal agency website announcing the main legislation facilitating the policy has just expired seems almost an insult.

In its post, the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) outlines that the Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Act 2012 (Cth) came to an end that day. The legislation was passed by Labor five years after the Coalition launched the Intervention, extending the policy for a further decade.

“The approach to the sunsetting of the Stronger Futures Act is… consistent with the Australian government’s commitment to self-determination,” the post reads, which is rather ironic as this paternalistic policy was all about stripping First Nations peoples of the right to control their lives.

Media beat-ups involving false child abuse claims served to justify the rollout, as demonised First Nations people were hit with a series of punitive measures impacting 73 remote communities, which included welfare quarantining, compulsory land acquisition and beefed-up policing.

But to conclude that the sun setting on Stronger Futures marks the end of the Intervention is to ignore that much of the neocolonial project’s key mechanisms are now established on the ground, while others are sanctioned within the provisions of legislation that continues to be in force.

Sinking below the horizon

The National Indigenous Australians Agency confirmed that the Morrison government held discussions with the Northern Territory government and the decision was made to simply let the Stronger Futures Act expire in line with its section 118 sunset clause.

And whilst affected NT communities, as well as local Aboriginal organisations and land councils, had been notified that the principal laws enabling the 15-year-old policy were expiring, the wider announcement was left to the recent message inconspicuously posted on its website.

On the day following the posting, NIAA published its Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory: Sunset Review on its site. Having been submitted to the federal and territory governments at an earlier date, the agency’s report recommended all the laws within the Act be dropped.

The document covers the three tranches of the Stronger Futures Act, which provided alcohol bans in prescribed areas, land reform and food security measures, and it also entailed NT communities-specific pornography bans that were contained under part 10 of the Classification Act 1995 (Cth).

The review further outlines that other interventionist measures, which involve “Aboriginal customary law in criminal sentencing proceedings, income management, school attendance and welfare reform” continue to apply under other legislation.

Discriminatory in nature

Officially known as the Northern Territory National Emergency Response (NTER), the Intervention was established via a package of legislation, with the principal piece being the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 (Cth).

And as this range of laws targeted First Nations people in the NT, the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) had to be suspended, which prevented communities specifically affected by the policy from being able to challenge its discriminatory nature under legislative protections.

The NTER laws provided the federal government with compulsory acquisition of five year leases over Aboriginal land, and denied the people compensation in return. The lands of 65 Aboriginal communities, previously held under native title, were compulsorily acquired in this manner.

The measures further provided for the exclusion of any relevance customary law might have on bail and sentencing decisions, as well as welfare quarantining with no right to appeal, and child support payments were linked to school attendance.

The government also abolished the Community Development Employment Projects, which saw thousands of First Nations people employed via the scheme that included a low working wage. And instead, these people were forced onto a work-for-the-dole program.

Just months after the Intervention began, the Rudd government took office and continued the policy. Although Labor did make some tweaks, which included the roll out of the BasicsCard, which makes 50 percent of welfare payments unavailable in cash to be spent only in approved stores.

And as the NTER laws were set to expire in 2012, the Gillard government enacted Stronger Futures and its related legislation, which extended the invasive policy until this month, as well as increased penalties for banned items, while enhancing the school attendance proviso on welfare payments.

What’s come to pass

The NIAA review makes a number of recommendations that are now in effect. These include lifting the blanket ban on alcohol, with the NT government maintaining them if deemed necessary, while remote communities have the option to opt in and continue with the prohibition.

In terms of land reforms, Stronger Futures created measures allowing for the privatisation of lands reserved for Aboriginal communities via NT law reforms to facilitate this. NIAA suggested the federal laws be dropped, whilst the NT government retains the measures under its own laws.

The third aspect to Stronger Futures was a community store licensing scheme to promote food security. An early review of this system found that poor quality food was still being sold at high prices, as it continues to be to this day. This scheme is now maintained under local laws.

The provisions facilitating the pornography bans and police powers to seize such material were contained in the Classification Act. NIAA recommended these be dropped as there was insufficient evidence of their efficacy, and their focus on hard copy materials had been foiled by the internet.

The Intervention remains

So, despite the sunsetting of the Stronger Futures Act, much of what it had implemented remains in place, while many other key interventionist measures, which weren’t contained in that legislation, also continue to apply.

The Albanese government this week introduced a bill to revoke the cashless debit card, which the Coalition began rolling out nationally in 2016. It works in a similar manner to the BasicsCard, but 80 percent of payments are quarantined, while there’s no restrictions on stores where it can be used.

What the new government hasn’t loudly announced is that to date, the BasicsCard continues to operate in prescribed areas in the NT. And despite promises to make it a voluntary scheme, right now around 21,000 people living in the territory are involuntarily on the card.

Then there are the other Howard-implemented interventionist measures that continue to apply. This includes the work-for-the-dole program, which erased community-based employment, along with the enhanced policing of remote Aboriginal communities by officers carrying military style weapons.

In the wake of the acquittal of NT police constable Zachary Rolfe for the shooting death of Warlpiri teen Kumanjayi Walker, the Karrinjarla Muwajarri-Ceasefire campaign has been launched. It’s calling for the removal of police guns from remote Aboriginal communities.

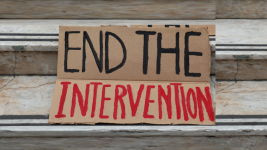

“The Intervention has torn us apart. It ripped us apart. We cannot allow that. We want the Intervention to be done away with,” Warlpiri Elder Ned Jampijinpa Hargraves told Sydney Criminal Lawyers last month.

“Intervention hasn’t given us an opportunity. Intervention hasn’t given us freedom of will or our rights to carry on the way we want to live.”

Those supporting the growing campaign to see heavily armed non-Indigenous police officers currently patrolling unarmed First Nations communities be done away with, are also calling for an end to the Northern Territory Intervention.

Yet, the control of these First Nations communities via law enforcement and the government withdraw of their agency is certainly not going to be withdrawn via the quiet passing of the set of laws in the Stronger Futures Act, which are no longer needed to continue the oppressive regime.