“Literally Black Sites”: Dr Julie Macken on a Royal Commission into Immigration Detention

With the High Court ruling last month that the indefinite detention of unlawful noncitizens in immigration centres is illegal, the resulting release of around 140-odd people from a form of detention without an end or a crime, the Albanese government has fallen into a fit of paroxysms.

The old and ugly fears middle Australia has harboured about asylum seekers arriving by boat and threatening its safety have risen to the surface yet again, with politicians, like Liberal leader Peter Dutton, purposefully whipping up a racist panic about them being amongst us.

The release of these people from the unjust grips of indefinite detention has led to the realisation that despite the official closure of the Manus Island facility in late 2017, and the evacuation of all the detainees from Nauru earlier this year, the nation still has an inability to deal with refugees.

Indeed, despite the apparent winding down of offshore detention, Albanese committed to keeping Nauru open on election. And now, there are around 20 new detainees on the island and as for those held on Papua New Guinea, 60-odd people have recently had their supports cut off after a decade.

Breaking the silence

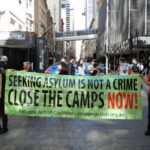

As the major parties were continuing to grapple with the release of those previously detained with no end in sight, Teal Independent for North Sydney Kylea Tink launched the Campaign for a Royal Commission into Immigration Detention on 28 November.

As campaign spokesperson Dr Julie Macken outlines mandatory immigration detention and offshore processing are still in place and despite the recent lull, if the policy underpinning this system is not subject to some form of official inquiry, then the horrors of the past will be revisited.

The system of offshore processing peaked around 2013-14. And in its wake, it has become apparent that those who’d arrived in Australian waters seeking the help of the nation were rather systematically punished and used as living scarecrows to warn off other would-be asylum seekers.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to campaign spokesperson Dr Julie Macken about the psychology underpinning the decision to punish foreigners seeking our assistance, the inability of the major parties to even contemplate reform and the stains on our nation’s reputation and psyche.

On 28 November, the Campaign for a Royal Commission into Immigration Detention was launched by Teal independent Kylea Tink and others at Parliament House in Canberra.

The others included author and former Manus detainee Behrouz Boochani, Amnesty International’s Zaki Hadari and Independent member for Clark Andrew Wilkie.

Dr Macken, as the member for North Sydney recalled during the campaign launch, you’re the instigator behind this campaign.

So, overall, why do we need a Royal Commission into the Australian government’s policy of detaining those who arrive in the country seeking asylum?

With the exception of the White Australia policy and the proclamation of terra nullius, no policy has so transformed the nation as has the immigration policy that we currently have.

I grew up at a time when we had a very different policy, from Whitlam through to 1992. We had a proud record of settling asylum seekers, of working with the international community and of resourcing those communities when they came seeking protection from Australia.

It was something we used to show off about on the international stage.

From 1992, and certainly it accelerated post-1996 with the election of the Howard government, the understanding of our relationship with asylum seekers as being one of a humanitarian relationship changed to being one of national security.

Most people would remember the image of the SAS boarding the Tampa to prevent 400 asylum seekers landing in Australia.

With that image, we understood our relationship with refugees and asylum seekers to be one that should be framed through a national security lens.

What followed from that was legislation that changed at warp speed. First, we had mandatory detention. Then we had offshore detention.

Then we privatised the offshore detention, making those sites almost black sites, in terms of accountability or even getting lawyers and journalists to look at what was going on there.

Then we had the spectacle of there being mandatory, arbitrary, and under Al-Kateb versus Goodwin, we had indefinite detention.

So, this is western democracy at a time of peace, suddenly, introducing the idea that an innocent person can be held for their entire lives in detention for something that is not illegal.

That is an extraordinary development. And since then, we have had endless allegations of the sexual assault of children, certainly of women, and we’ve seen up to $30 billion spent on these camps since 2002.

None of us have a clear idea of where that money went, because it is all hidden behind commercial in confidence contracts.

We have seen the architect of Home Affairs, Michael Pezzullo, sacked for his behaviour.

We’ve seen the tendering process clearly corrupting the politics around PNG and certainly, around Nauru. Nauru is looking like a failed state now.

The impact of this policy has been extraordinary on our legal system, on the fundamentals of our law, and it has also been pretty devastating on us as a community of people in Australia.

In a lot of ways, we know things about ourselves and each other that we could never have known prior to 1996.

These are things like knowingly voting for a policy that we know abuses children and that drive families insane. We know it completely destroys what psychiatrists call the sacred core of a person.

And in election after election, we voted for that policy. It is pretty extraordinary, Paul. So, at some point, we need to review such a powerful and transformative policy.

We need to review it now with a Royal Commission because only a Royal Commission has the powers to coerce both government and corporations to produce the necessary documents, the contractual arrangements that were done and the amount of money that was spent.

Only a Royal Commission has the capacity to protect the evidence and the witnesses as former workers at these centres and as people detained under this regime – only a Royal Commission has that power.

And the final points about a Royal Commission are that Australians don’t trust anyone very much at all anymore, according to all the trust indexes. In fact, we have never been so distrusting and our social cohesion has never been more fragile.

But we do still trust Royal Commissions and that is why people keep asking for them.

With the intractability of both major parties blocking any reform in this space, a Royal Commission is something the broader Australian community trusts to find out the truth without the politics.

The final thing is it is often said that both major parties have this policy. However, I would argue that this policy has both major parties. Both majors are unable to change this policy at all except to tighten it and make it even more draconian.

They have actually lost the capacity to review and retool this policy into a humane proposition.

So, it is best taken out of their hands and put into the kind of cool courtrooms that a Royal Commission would create. It would take it out of the political process and put it under some scrutiny.

Tink outlined at the launch that between 2001 and the present day, with just a brief pause between 2008 and 2012, tens of thousands of people seeking Australia’s protection have been held at offshore locations in Nauru and in PNG.

And as this regime developed post-2013 it became notorious globally. So, how do you account for our nation having developed such an infamous system for dealing with people, who are fleeing persecution in their homelands, in terms of its cruelty?

It is a really important question that we have to ask ourselves: how did a nation like Australia, with a good track record of human rights defence and care of the Other, in a time of peace, how did we create these camps, turn them into black sites and give private prison companies free rein over them, fund them to an extraordinary level and feel good about it?

What was going on so that happened? It is cold comfort, I guess, but I have just written a PhD on exactly that question: why have we done that?

There is massive debate internationally about what Australia has done and why Australia has done it.

My thesis is looking at the nation psychoanalytically, which sees the nation denying its foundational violence in the colonisation of the continent and in denying the fear around our coming by boat.

White Australians came by boat. Australia today treats asylum seekers very differently if they come by boat.

If you are one of the 90,000 to 100,000 people who fly into Australia every year and, on arrival, apply for protection, you will probably be settled in the community, and they will eventually get around to checking your protection needs.

But if you arrive by boat, if you are one of the handful of people, relatively speaking, that arrive by boat, the nation goes completely hysterical.

You will be taken to an offsite camp, and you will be treated in an abusive, degrading and inhumane manner. And those aren’t my words, that is the opinion of the International Criminal Court, when it was asked to give an opinion on asylum seekers in Australia’s regime.

The ICC said these people are clearly treated in a cruel, degrading and an inhumane manner. On the question of torture though, they said because we don’t believe the abuse of these people is serving any political function, we can’t find that it is torture.

Now, they got this wrong. The detention of these people is providing a political function, which is sending a message to others not to come.

For me, this is tied up in White Australia’s denial of foundational violence in our colonisation when we came by boat.

Melanie Klein and Sigmund Freud all talk about what happens if we don’t deal with the reality of where we come from. Then we slip off into a state of melancholia.

Melancholia is a state characterised by narcissism, by a shallow engagement with life and by a loss of capacity to love. I can’t think of three better ways than to describe the state of Australia better.

Until we come to grips with the reality of how modern Australia was formed, we will always be looking to the Other to carry all the psychological material we are unwilling to carry.

That kind of thinking will drive most lawyers insane. But in a former life, I was a journalist and a political consultant.

I am used to looking at the facts, absolutely. And I went to look at it psychoanalytically, because it defies the facts. It absolutely defies rational thinking that Australia would destroy people in this way and also destroy our trust in each other by doing that.

So, if it is not rational, then it must be unconscious.

The opening of the campaign involved former detainees. What sort of practices do they want to see exposed? And what overall impact are you hoping such an inquiry will have?

I won’t speak for them. But they wanted to be central to this campaign because they had to live in these camps, which were almost operating as psychotic pockets for the nation.

Those people had to live in these psychotic pockets and endure the kind of abuse that every time I hear any detail of, I am left in tears. I find it quite shattering as an Australian.

They want the reality of what they lived with known to Australia.

The former workers are also campaigning for this. A couple of them I spoke to were young social workers who went to Nauru to try and help because they cared.

One of them said to me that she saw our country abuse young women in such an horrific way that if I told you about it, I would potentially go to gaol for two years.

“Not even domestic violence survivors live with that hanging over their heads. They are allowed to speak. I am not even allowed to tell you what I saw,” she said. “I don’t want to live with my nation’s dirty secrets, anymore.”

If we want this policy to change. If as a nation, we want to have a legal, humane and sustainable immigration policy, frankly, the way we used to have in Australia, then the social licence for this policy has to be destroyed.

You destroy a social licence by revealing the operations of the corporation you are targeting or the country you are targeting.

The truth would destroy the social licence for this policy, and once that happens, people would be desperate to develop a new policy that we could all be proud of.

A lot of refugee advocates point to the neglect of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, as rather than follow those international laws that our nation is a party to, it patches togethering the rules in the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) at its own convenience.

Should the international convention be given more weight? And what do you think about the way both sides of politics have been legislating in regard to immigration?

Both sides of politics are, quite simply, neurotic about this. They are cowardly and their policy is enfeebling us as a nation. It is a very neurotic response.

Don’t take my word for it, Christine Nixon did a brief review of what she saw within our visa system, and three or four weeks ago, excerpts from that report were commented on by Clare O’Neil and what Nixon said was because governments of both persuasions are so obsessed with people arriving by boat, they completely missed the point that thousands of people are flying into Australia and some of them are very bad people.

Curiously, this obsession with asylum seekers means we are far more vulnerable to bad actors that fly in. The two parties are very neurotic about it.

But in terms of the convention, we just need to comply with the Refugee Convention we signed up to.

And it would also be good if we could comply with the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture. We are one of 15 countries that didn’t comply with it.

We are outliers in terms of our international treaty obligations in all sorts of ways. And the only people who think that doesn’t matter are Australians, because I can assure you the rest of the world knows that Australia has turned into this little aberrant outlier nation.

With the Albanese government coming there was hope that it might improve on our failing international standing regarding human rights. Would you say the new administration has made any improvements?

No. We have seen zero evidence that the Albanese government has been interested in saving any of our international reputation as a good human rights citizen of the world. There has been zero.

We have seen the promise of 19,000 refugees being put on permanent protection. For the record, nothing like that record has been made permanent yet, and aside from that, we have seen nothing change.

We’ve had Clare O’Neil, the home affairs minister like the Queen of Hearts, screaming, “Off with their heads. Off with their heads.” If she had her way, everyone would remain in detention forever.

Well, thanks, minister. But we still are, in whatever shape, a democracy where the rule of law still does matter somewhere.

So, not only have we seen no moves at all to repair our once really quite impressive credentials as a human rights defender, but we have also seen the minister in charge of this, trying to outdo Dutton.

I have no idea what she was up to, but her behaviour was completely shameful.

A major hole in the Australian government’s immigration detention regime was recently exposed and brought to an end when the High Court ruled that the executive cannot indefinitely detain stateless people or those it cannot return to their country of origin.

What are your thoughts about this ruling and the commentary that’s been apparent in its wake?

The High Court has reasserted the rule of law. The Al-Kateb ruling was pretty whack, frankly. So, it has really reestablished legal norms in Australia, which is very good, as we are all protected when legal norms are established and maintained.

The behaviour, as I keep saying, has been political and dehumanising for all those people detained through Australia’s policy.

I understand that 20 of the 142 asylum seekers that have just been released, were gaoled as a result of very serious violent crimes.

But, I’d just like to walk people through this very slowly, Paul, because we seem to have forgotten it.

In Australia, we have got this whole set up where if you do the crime, you do the time. And when you finish doing your time, perhaps if you are still on parole there are certain criteria and things you have to do, but, by and large, when you finish that sentence, you have finished that sentence. That is how we operate in Australia.

Labor minister O’Neil wants to change that. She wants to introduce the idea that when you do the crime, you do the time and then we hold you forever. You never ever get out.

You’re either literally in gaol or you are under curfew with a massive security bracelet on forever.

This is like taking a hammer to the head of this nation and saying, “We are going to radically change the law that much.”

Now, she would say this isn’t the case as the scheme is only for asylum seekers. And she could go further and say, “That’s only for particularly brown asylum seekers. It only applies to a certain type of people.”

But history has told us time and again that isn’t how the world works. When you apply such laws to a certain people that community only grows and grows and suddenly, in Australia, if the parliament doesn’t like you then you can be held forever: citizen or not.

This is a really dangerous development for all of us. It is shameful that the Albanese government is really enfeebling one of the essential pillars of our legal system like this. It is terrible and it is dangerous.

And lastly, Dr Macken, what sort of political will is there for such an inquiry or would you say that there is political resistance to such a move? Could the outcomes of such an inquiry trigger further investigation by a body like the NACC?

Starting at the end first, the Royal Commission would create a whole lot of referrals to the NACC.

The reason to start with the Royal Commission, rather than the NACC, is that the NACC needs a certain degree of information to get wood under the wheels of any kind of investigation.

These places are literally black sites. So, to get the sort of information that the NACC would need to begin to process these issues, you need to start with a Royal Commission.

The political will, certainly, within the Greens, the crossbenchers and the independents is very strong. People who have an interest in human rights, the reputation and basic matters of justice in Australia are extremely keen to see this commission get up.

The opposition from Labor and the Coalition is in lockstep because both of them have been involved in the appalling treatment of detainees through this policy.

So, of course, they are fairly interested in protecting their political hides and it is going to be extremely difficult to get a Royal Commission up for that reason.

That said, I would say it is in Labor’s interest to do it, because we are asking Labor to go back for a decade. We can’t go back to 2000. A Royal Commission can’t cover a quarter of a century, but it can cover a decade.

During that decade, it was the Coalition running the camps. So, I can’t see there is much damage for Labor in holding the commission at this point.

You will no doubt be aware there are already 20 people being detained on Nauru again. These camps are going to reopen again – no doubts about it – like they did under previous Labor governments and then Labor will really be implicated in this abusive behaviour.

Without a Royal Commission this treatment is not going to change. We have seen 25 years that tell us it can’t change.

I mean, the Coalition is utterly opposed to it. But that seems what the Coalition exists for: to oppose everything, and in particular an investigation like this.

Dutton’s participation in the immigration system was critical over this period. So, was that of Morrison and Turnbull, and certainly, so was that of Tony Abbott.

So, none of them would see reason as to have a forensic investigation into how these places were run and maintained under them.