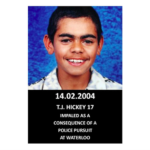

The Hickey Family Continue to Demand Justice for TJ, 20 Years On

Protesters gathered at TJ Hickey Park at Waterloo Green amongst the public housing towers on 14 February, to mark the 20th anniversary of the death of a 17-year-old Gomeroi boy, whose name the park now bears, as he lost his life being pursued on his bike by two NSW police paddy wagons.

Aunty Gail Hickey, TJ’s mother, the Hickey family and their supporters convened at the site on Gadigal to continue the call for justice over the death of TJ two decades on, as they assert that state authorities have attempted to conceal the truth about the Aboriginal death in custody.

The hunting down of the First Nations teen, who’d committed no crime, led to his death in a hospital the next day, which struck a chord across the continent and led to rioting in Redfern, as local Aboriginal people revolted against a racist law enforcement body that treats them like the enemy.

Then NSW state coroner John Abernethy found at the August 2004 inquest that although senior constable Michael Hollingsworth mounted a curb to follow TJ on his bike down a footpath, both police vans were not in pursuit of him, and therefore, weren’t in violation of police protocol.

Indeed, when the Hickey family and the Indigenous Social Justice Association (ISJA) presented then NSW attorney general Mark Speakman with a 2020 petition, containing over 12,000 signatures and calling for a parliamentary inquiry into TJ’s death, the state’s chief lawmaker refused the request.

Pursued for being Black

“A young boy was innocently riding his pushbike through his local neighbourhood, when he came to police attention, who thought there’s a little black fella on a bike, he has to be committing a crime or riding a stolen piece of property,” Lizzie Jarrett told the crowd in TJ Hickey Park.

“So, they took it upon themselves to pursue that young boy,” the Gumbaynggirr Dunghutti Bundjalung woman continued. “We now stand in front of the fence where young TJ ended up impaled and tragically lost his life, all due to the pursuit and chase of the Redfern police.”

The coroner determined that even though the paddy wagon Hollingsworth was driving mounted the footpath and followed TJ down it, this did not mean that he was being pursued, which would have breached police policy, and, as they weren’t chasing him, they didn’t cause the death.

Abernethy remarked that constable Maree Reynolds, who was the passenger in the van, was a bad witness because she couldn’t remember the details of the incident, whilst Hollingsworth had been difficult as he refused to testify, after providing three different versions of events before the inquest.

The coroner then chided members of the Redfern community in the courtroom as he completed his summing up, telling them that they could then stop spreading “rampant gossip and innuendo” about the police being responsible for the death of the teenager.

“All because of why?” Jarrett asked of the reason behind TJ’s death. “He was a young Black boy riding a bike – that’s the reality of how he lost his life.”

State of siege

Standing at TJ Hickey Park 20 years on, it’s hard to see how two police paddy wagons following a teenager on a pushbike, with one van continuing onto a footpath behind him, whilst the other took another road route to hopefully head him off, was then not considered police pursuit.

But as Wiradjuri Yuin woman Angeline Penrith tells it, people, including children, from First Nations communities are being killed constantly in Redfern and elsewhere, without accountability. She said she rarely lets her kids go outside because it’s dangerous, and that’s the way it’s been all her life.

“Every Black youth in this neighbourhood, and I dare say every Black neighbourhood, every mission, every area you go, is highly overpoliced by grown men with guns – organised gangs,” the Redfern resident told those gathered in support of the Hickey family.

“They don’t respect us. They don’t respect our women. They do not respect our men. They do not respect our kids,” she continued. “We are losing our kids. We are losing our men. Our women are being targeted and our kids are being taken.”

Penrith made clear that there is “not one part of Aboriginal life that isn’t attacked by colonisation, by white people”. And she underscored that the fate that became TJ could have happened to her when she was growing up, or it could happen to any of the First Nations kids today.

The colonial project

Another suspicious aspect regarding the incident is that police officers pulled TJ off the fence he was impaled on before the ambulance arrived, which is not in line with training for such emergencies, and eyewitnesses say the teenager was screaming out that he was going to die.

“Our people have been running from this government and police since colonisation. It was no accident what happened to TJ,” said Gwenda Stanley, a representative of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. “The biggest crime in this country is being an Aboriginal man.

“I remember TJ as a young boy. I recall being on the Block, back in the ’80s, when TJ was only a baby. His sisters are here today, and my cousins, they were there with him,” the Gomeroi woman continued.

“When you look at the Aboriginal deaths in custody, especially in NSW, you will see that they are Gomeroi men.”

Stanley went on to explain that being a Gomeroi man was TJ’s crime as well. She further recalled police bashing Aboriginal people in the local Redfern pubs in the 1970s.

Prior to the NSW Police Force, there was the Native Police, she added, and before any organised “law enforcement” it was an “open killing field” as the British sent the military on to Gomeroi Country.

“What you see here today, 20 years later, is the continuation of genocide in this country. We demand justice,” the Gomeroi woman made clear. “We demand restitution, reparations, justice and freedom for our people.”