“A Steady Deterioration in Rights” in Australia: An Interview With HRMI’s Thalia Kehoe Rowden

When the United Nations General Assembly announced that Australia would be serving on the UN Human Rights Council over the 2018-20 term, questions were raised about the nation’s fitness to hold a seat, especially in relation to its treatment of First Nations people and asylum seekers.

Australia ran on the basis of five pledges regarding how it planned to improve human rights. These included gender equality, good governance, freedom of expression, the rights of Indigenous peoples, and building capacity to improve rights institutions, especially in the Indo-Pacific.

Although the Morrison government seems to have missed the memo detailing the pledges when it took office in August the following year, as the Coalition has since excelled in gender inequality, stamped down on political expression, ignored First Nations peoples and picked a fight with China.

While at the UNHCR’s universal periodic review in January, Australia was condemned by other nations for its high rates of First Nations incarceration, the age of criminal responsibility being still set at 10 years old, as well as for its ongoing use of offshore detention centres.

Measurements to act on

Launched in 2017, the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) tracks how nations are doing in regard to upholding human rights, and provides a score in relation to thirteen different rights metrics, so that over time governments are able to gauge how they need to improve.

The rights that HRMI is monitoring are taken from the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Our nation has ratified both treaties, meaning it has agreed to adhere to their provisions.

The initiative further breaks down rights into three groups. There is quality of life, which consists of economic and social rights markers. While the measurements within the two other categories – safety from the state and empowerment – consist of civil and political rights.

The data is then collated in a database known as the Rights Tracker. It provides a snapshot of how a country is tracking in terms of upholding human rights, or it can also give you a rundown on how all countries are tracking in relation to a specific rights metric.

Torture and ill-treatment

The 2021 HRMI report on Australia outlines that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continue to suffer widespread human rights abuses, while it found that refugees and asylum seekers are “particularly vulnerable to abuses of every single right” the initiative measured.

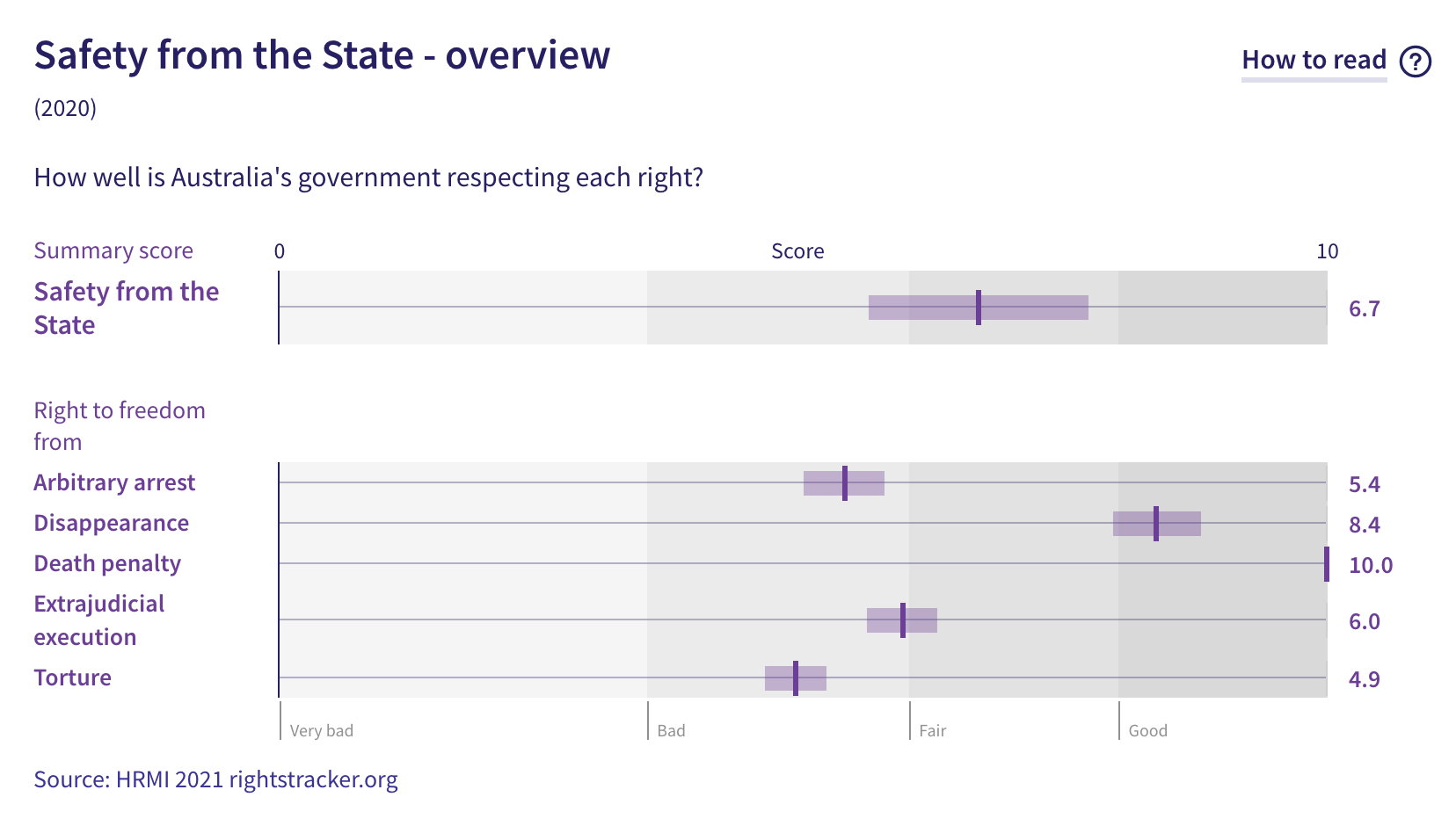

The report also draws attention to our nation’s very poor rating in terms of the right to freedom from torture and ill-treatment. Australia scored 4.9 out of 10 in this regard, as the experts consulted set out that there are a large range of people in this country at risk of having this right violated.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to HRMI strategy and communication lead Thalia Kehoe Rowden about how our nation compares with hers, the reason why Australia rates poorly in terms of torture and ill-treatment, and the difference between civil and political rights and social and economic ones.

Firstly, this year’s Human Rights Measurements Initiative figures have just been released. The initiative tracks how 203 countries are comparatively rating in terms of upholding human rights using a variety of metrics.

So, Thalia, as the initiative is partly based in New Zealand, where you reside, how does our country compare with yours?

We are a global research team, which is based all over the world. We have two main institutional bases: one in New Zealand and one in the United States.

As a New Zealander, it gives me no pleasure to say that our nation is performing better than Australia on all of the rights metrics we use.

But I want to clearly say that New Zealand has many of the same problems that Australia does with human rights. So, it’s not to say that New Zealand is a shining example that’s better than any other country.

We are always trying to do better with human rights, as every country should. That’s the obligation under international law – to keep doing better.

With our civil and political rights scores, anything less than a 10 can mean that most people in a country are fine, but there are groups who aren’t enjoying the human dignity that we all agree everyone should.

So, from the outside, it may look like countries such as Australia and New Zealand should be scoring brilliantly, because we’re wealthy western democracies.

But, certainly, both countries have large groups of people who are vulnerable to rights violations, and who aren’t living the good life that we expect all people should have.

Australia scored poorly in relation to torture and ill-treatment. Indeed, the HRMI site states that this country has a serious problem in this regard. This may come as a surprise to many living here.

So, from the data, what’s leading our nation to rate so poorly on this metric?

The data is pretty clear about that. There is a long list of around twenty different groups that human rights experts have said are at risk of torture and ill-treatment at the hands of the state.

While it’s true that a large percentage of Australians have never experienced torture or ill-treatment and may never, there are groups of people who do not feel safe and have experienced ill-treatment or know people who have and feel that they’re at risk too.

Right at the top of that list is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. There’s a near unanimous agreement amongst human rights experts that we consulted that Indigenous people in Australia are at particular risk of torture and ill-treatment when they come into contact with government agents.

That might be in situations of detention. It might be in interactions with police. It might be in situations of healthcare or social welfare.

There are definitely vulnerable groups in Australia who are not protected at the moment.

So, what are some of the other groups included on that list?

Refugees and asylum seekers come up again and again in our data, especially people who have arrived by boat. This is due to indefinite detention and the conditions these people are contained in. Offshore detention centres are mentioned frequently.

We also had some new information on the situation with the pandemic. We have several comments around how people were not being treated well, particularly elderly people who were in residential health facilities.

There are further issues around the conditions in youth and adult detention facilities, including with the use of solitary confinement. And there were also problems with the treatment of people with disabilities.

As you’ve mentioned the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are being undermined in Australia. HRMI tracks Indigenous rights in all the nations it covers.

So, how does Australia rate comparatively in this regard?

In terms of Indigenous people, this is close to universal. Indigenous people feature very often at the top of our list in terms of those who are facing rights violations.

Certainly, in Australia, it shows up as a major problem, as it does in New Zealand and the United States, as well as many other countries.

What are some areas where Australia is tracking well in terms of human rights?

One clear example is that everyone in the world has the right to freedom from the death penalty. And Australia is one of the countries that has had that sorted for some time.

Australia gets a 10 out of 10 for freedom from the death penalty, which should not be taken for granted. It can seem like it’s not a real measure, because we assume that this is the case.

But there are certainly plenty of other countries, including the United States, that still practice the death penalty.

Freedom from enforced disappearance is another metric that falls into the good range.

But I’m afraid that’s the only two out of the thirteen scores that fall into the good band. So, there is significant room for improvement.

The first HRMI workshop was held in 2015 in the United States. This year is the fourth year that it’s published its findings.

Why is a project like HRMI needed? What does the initiative seek to achieve?

We work on the principle that what gets measured gets improved. We know that the people who can change the human rights situation in a country are primarily political leaders.

We know that leaders like numbers. If a person is running a country, they will be wanting to know what the GDP is, as well as what their long-term employment rates are, as those kinds of numbers help make decisions.

Before this initiative, there were no numbers on human rights. There were lots of organisations monitoring them, and reporting on particular cases, but there were no scores.

People often ask how what we’re doing differs from the United Nations. But the United Nations doesn’t measure human rights at all. It monitors them, but there are no objective measurements to show whether there’s any improvement or deterioration.

That is what we show, which means people can go to their government, say that the nation has this score that’s going down, and ask what is going to be done to lift it.

We hope that leaders will bring in their advisers to work out how they can improve their scores by looking at what laws and policies need to change in order to boost human rights so that people will be treated better in their countries.

HRMI measures a series of different rights metrics. However, it breaks down human rights into two broad categories: civil and political, as well as social and economic.

How would you describe the difference between these two sets of rights?

We have them in two different categories because within the United Nations treaties, which countries have signed on to, there are completely different obligations in relation to rights.

This is all about the wealth of a nation. Civil and political rights are things like being free from torture and the right to free speech. A country’s wealth doesn’t influence those.

No country is allowed to violate any civil and political rights. That’s whether they’re rich or poor. It shouldn’t make any difference.

Whereas with economic and social rights – such as health, housing and education – a very poor country isn’t expected to have a health system as good as a very wealthy country.

Yet, a person in a poor country still has the human right to adequate healthcare and a good education.

The way the obligations in the treaty works is that all countries need to do the best they can with what they have.

So, what we measure is whether the countries are doing as well as we think they could do given how much money they have. We calculate it using econometric techniques.

We can now say to a country of low or middle income that they are doing as well as they can, or they could be doing better, as they could achieve more with the money they have.

That is quite a powerful thing to be able to say to a government, that it is not limited by wealth. Especially when you can compare with a neighbour who might be doing a lot better with the same income in terms of more kids in school or better life expectancy.

And lastly, Thalia, looking back over the years of HRMI findings, how is Australia tracking over time? If we continue on the trajectory we’re already on, what should we expect?

I’m sorry the news isn’t great because almost all of Australia’s scores are tracking slightly downwards.

Freedom from disappearance is going up, so that’s great. But it was already a high score.

I would have some concerns about all of the other scores. We have been measuring Australia for four years now and we are seeing a steady deterioration in rights.

So, it would be great for the Australian government to take a good look at what’s driving those changes and see what needs to be improved.