Albanese “Is Not a Prohibitionist at Heart”: PM’s Political Roots Include Drug Law Reform

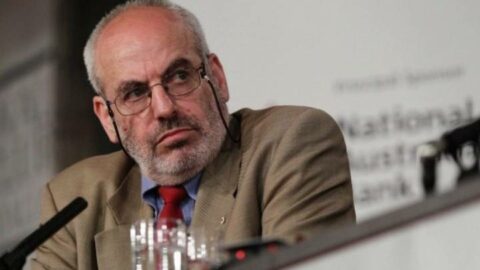

“The speech made by Anthony Albanese in parliament on 22 March 1999 makes it clear that Australia’s new prime minister is not a prohibitionist at heart,” said Harm Reduction Australia ambassador Dr Alex Wodak.

The doctor pointed Sydney Criminal Lawyers in the direction of the speech, which sees Albanese, then a federal Labor opposition MP, critiquing former PM John Howard’s decision to shut down plans to establish a heroin prescription trial in the ACT as “blinkered and short-sighted”.

Drug law reformists often lament Howard’s decision to “trash” the six years of “careful scientific work” that had gone into the trial – which, as Wodak outlined in 2007, had widespread bipartisan support nationally – as it served to stymie the nation’s then successful harm reduction agenda.

Albanese condemned Howard’s reactionary move, setting out in the lower house that “to say the reason” that some drugs are “legally sanctioned” while “others are outlawed” is “to do with public health and safety is a nonsense”.

“The drugs responsible for the most deaths and diseases… are not heroin, cannabis, ecstasy or cocaine. They are alcohol and tobacco,” the current PM said, adding that deaths weren’t caused by heroin itself, but due to its “uncertain purity” and adulterants, which are byproducts of being illegal.

A health issue, not a crime

Howard brought an end to the heroin trials in August 1997. Cabinet ministers broke ranks to condemn the move. The conservative prime minister told Channel 7’s Sunrise in April 2002 that his main concern about the prescription heroin trial was it would “send the wrong signals”.

“It is simplistic to say that decriminalising illicit drugs, sanctioning safe injecting rooms or undertaking heroin trials send youth the wrong message,” a younger Albanese said.

“To my mind, the sort of message it sends out is that drug dependence is a medical, not a criminal, problem.”

“But it is not the heroin per se that causes all these problems,” the new prime minister continued, “it is often the criminalisation of the supply and use of heroin.”

An act of civil disobedience led by Wodak in 1986 led to the rollout of needle and syringe exchanges nationwide, while he was key in seeing the Kings Cross safe injecting room established. And the move to trial prescription heroin was due to a suggestion he made to a 1989 parliamentary inquiry.

Albanese said in March 1997 that it was the government’s responsibility to give the trials a go. The ANU centre for epidemiology commenced its research into the proposal in 1991, which it ultimately found to be an effective way to treat a small group, who’d been failed by other treatments.

Words worthy of a leader

In his 1997 speech to the chamber, the current PM referred to a statement that Wodak had made about the trials, which maintained that “any doctor who is trying to… treat people with a very complex difficult condition like heroin dependence, really wants the maximum range of options”.

Albanese then condemned Howard’s zero tolerance approach, as it involved locking up both those using the drug and those supplying it, which ultimately leads to heroin dependent people spending longer terms in prison, and the drug itself rising in price, hence more crime.

“As long as drugs remain in the domain of law and order or the bottom priority of health budgets, thousands more people are going to die,” the Labor MP concluded in 1997.

“These deaths are needless. Please listen to the pleas of those who have lost loved ones and do something effective.”

So, as Canberra moves to decriminalise drugs and the legalise cannabis vote in last month’s federal election was substantial, it seems drug law reformists currently have a likeminded ally in the highest office this term.