As Lockdowns Lift, the COVID Policing Hangover Is Coming

Soon the lockdowns will end. The disparities in the enforcement of public health measures will disappear. Most who have been forced to stay at home will return to work. The vaccination drive will end. And there will be no more anti-lockdown protests.

But, as life in the community begins to take on a semblance of what it was like before the pandemic, it will never be entirely the same again.

And one aspect to the COVID-19 period that will likely remain is the shift in policing methods that has occurred whilst the virus was lurking.

As NSW police commissioner Mick Fuller has made clear, this state’s law enforcement approach to COVID-19 has been to treat “the virus itself as a criminal”.

So, considering that the nature of pandemic policing is preemptive – and the impossibility of on-the-beat officers actually capturing COVID-19 and locking it up – this approach has meant that all potential carriers of the virus have been treated as crime suspects.

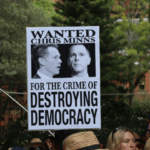

Meanwhile, down in Melbourne, Victoria police found the recent antivaccination mandate protests an opportune time to whip out its non-lethal weaponry and use it upon the citizenry, which was a first – but likely not a last.

Indeed, in the coming months, public health fines, and demonstrations aimed at lockdown restrictions and vaccine requirements will fade, but the police overreach that has occurred won’t.

Arresting your way out of a pandemic

The approach to the global public health crisis in NSW, as elsewhere, has been one that relied on measures to curb the virus, coupled with a heavy-handed policing approach to enforce them.

However, health measures don’t seem reasonable while they’re administered via point of gun.

Commissioner Fuller was placed in charge of the NSW COVID response right from its onset at the end of March last year. This, again, sent a confused message to citizens going through extreme shock after just having been locked down for the first time in their lives.

Isolating and mask wearing are designed to stop the transmission of an airborne virus, yet the lockdown and restrictions on behaviour were implemented when public distrust in government institutions was at an all-time high, so, therefore, the ground was fertile for conspiracies.

In the early days of COVID, there were absurd stories about a man being fined for eating a kebab on a bench, then came a Victoria police officer assaulting a woman over not wearing a mask, which was later followed by the recent seizure approach taken to southwest and western Sydney.

The Policing Biosecurity academic report found that police statistics relating to the three months ending on 15 June last year, reveal that once NSW police stopped a person over a suspected COVID breach, 45 percent of individuals were then searched. And this was not for having the virus on them.

Weapons that can maim

Melbourne has been the flashpoint of police brutality by cover of COVID. At the anti-lockdown protests in mid-August, Victoria police announced that it had used “a range of non-lethal options including pepper ball rounds and OC foam cannisters”. And it claimed it was forced to do so.

This marked the first time they’d ever been used. The weapons were bought as part of the Victorian government’s 2016 Public Safety Package, with the official reasoning for acquiring them being the so-called African gang crime wave, and heated protests that saw the alt-right and the left facing off.

Heavily clad Victoria police officers aimed and fired VKS 175 shot pepper ball semi-automatic rifles at unarmed protesters, as well as using Oleoresin capsicum spray, which is trigger released from a cannister. And while these types of weapons may be “non-lethal”, they can blind and maim.

“Using, drawing or threatening use of any weapon is considered a ‘use of force’ for which a police officer is both legally and organisationally accountable,” said Melbourne Activist Legal Support (MALS) in a statement issued on 22 August.

“Victorian police officers do not have unrestrained power to use weapons or any other force on members of the public.”

The use of these weapons on civilians is perhaps the most detrimental shift in policing tactics that’s occurred over the last 18 months. And while “freedom” protesters are likely to become a thing of the past, a precedent has been set whereby police can use such arsenal on public protests.

Ever-present brutality

But while there has been an increased police presence on the streets, and new heights of overreach have transpired, the fact that Australian law enforcement is willing to apply extreme force upon members of the public hardly comes as a surprise to communities on the margins.

One of the reasons the police brutality of late has caused such outrage amongst the wider public is that at times it has been targeting relatively affluent members of the community.

Co-author of the Policing Biosecurity paper, UNSW Faculty of Law senior lecturer Dr Vicki Sentas told Sydney Criminal Lawyers not so long ago, that COVID policing has for the most part reinforced the prejudicial police targeting of certain sectors of society.

In regard to those police search statistics contained in the paper, First Nations people accounted for 10 percent of those searched and 15 percent of those subsequently arrested following a COVID stop. And this is despite their making up just 3 percent of the state’s population.

Seventy four percent of Aboriginal people stopped for COVID reasons were then searched, compared with 63 percent of non-Indigenous people.

Similar disparities were seen during this year’s lockdown, as the less affluent multicultural communities of Sydney’s southwest were subjected to a heightened police presence, with stricter pandemic rules, and later, an accompanying presence of Australian Defence Force troops.

As Sentas put it, “We saw this playing out in the very different ways that a paramilitary style mounted police presence in southwest Sydney could be contrasted with far less of a heavy presence at the height of the pandemic in the northern beaches or eastern suburbs.”