As the Cry Against War With China Rises, the Uyghur Crisis Should Not Be Downplayed

The political rhetoric of conservative politicians in Washington and Canberra has been marching us towards war with China for a number of years.

Indeed, renowned Australian journalist John Pilger warned of this rising threat of American Empire in his 2017 film the Coming War With China.

But it was the blatant pro-war posturing by newly-minted defence minister Peter Dutton in early May that really brought the understanding that the Morrison government – along with new boss the Biden administration – has gleefully led us into what the minister refers to as “grey-zone” warfare.

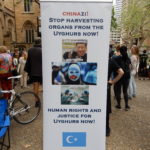

As US journalist Chris Hedges has pointed out, part of the justification for entering into a cold war with China has been the plight of the Uyghur people in the west of the country.

Beijing has been incarcerating around a million of this Muslim Turkic people without charge or trial in a system of newly-constructed internment camps in Xinjiang since 2017.

In March this year, the EU, the UK, the US and Canada passed Magnitsky legislation which placed joint sanctions on Chinese officials involved in violations against Uyghurs.

This saw western nations, which had initially ignored this human rights crisis for many years, acknowledge it and act upon it.

Progressive political commentators have pointed to this promoting of the Uyghur cause as being a tool of the warmongers, which it has been to a degree. However, some observers have gone as far as to downplay the bleak oppression the Uyghurs have been suffering to counter the push for war.

An oppressed people

“I don’t think the aggressive turn in Australian politics towards China is helping anyone inside China,” explained Sydney University senior lecturer in modern Chinese history Dr David Brophy. “But the first principle of political activism is to tell the truth.”

Brophy has travelled to the far western province of Xinjiang for the last two decades. His most recent visit was in 2017, following the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) having unleashed an ongoing crackdown on Uyghur civilians, but prior to the news breaking on the internment camp system.

World Uyghur Congress president Dolkun Isa explained in May 2018 that up to a million Uyghurs were being detained in and disappeared into “re-education camps”. This program began operating in April 2017. And Isa was campaigning to get foreign governments to pay attention.

“It’s an intense campaign of social engineering. People are being put through indoctrination programs,” Brophy continued. “There is pressure to assimilate to mainstream Chinese culture. The party is adopting measures to pull people out of traditional social environments.”

The academic further told Sydney Criminal Lawyers that on his last trip to Xinjiang a just implemented system of “grid-style” social management was in play. This involves numerous police stations, surveillance cameras, 24 hour patrols and checkpoints throughout urban areas.

Seven decades of Beijing rule

The CCP began its repressive rule in the homelands of the Uyghurs in 1949. And it established a “state within a state”, which is run by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps: a paramilitary organisation charged with development, securing the border and maintaining internal stability.

Beijing has been operating a transmigration program into the region, so the estimated 11 million Uyghurs now make up only 45 percent of the population. And despite China’s one-child policy having been lifted nationally, a two-child policy was placed on Uyghurs in 2017.

Laws restricting Uyghur culture have increasingly been passed for decades. Mosques have been closed. The growing of long beards and wearing of veils in public is prohibited. Uyghur language is being banned at schools. And the children of those detained are placed in state orphanages.

“The long-term survival of Uyghur culture is in doubt. The language is becoming increasingly marginalised,” Brophy said. “The CCP are comfortable with a very circumscribed version of Uyghur identity, one that the party will define the limits to the expression of at all times.”

One of the main issues commentators of the left have raised is that conservatives have classed this as genocide. The definition of genocide in article 2 of the Convention, includes killing, serious mental or bodily harm, calculated physical destruction, the preventing of births and child removals.

Sanctioning Beijing over Tibet

The crackdown Brophy witnessed the beginnings of was implemented by Chen Quanguo, who was appointed Xinjiang province CCP secretary in August 2016.

The party strongman is notorious for having first imposed the same surveillance and policing system in the region of Tibet over 2011 to 2016.

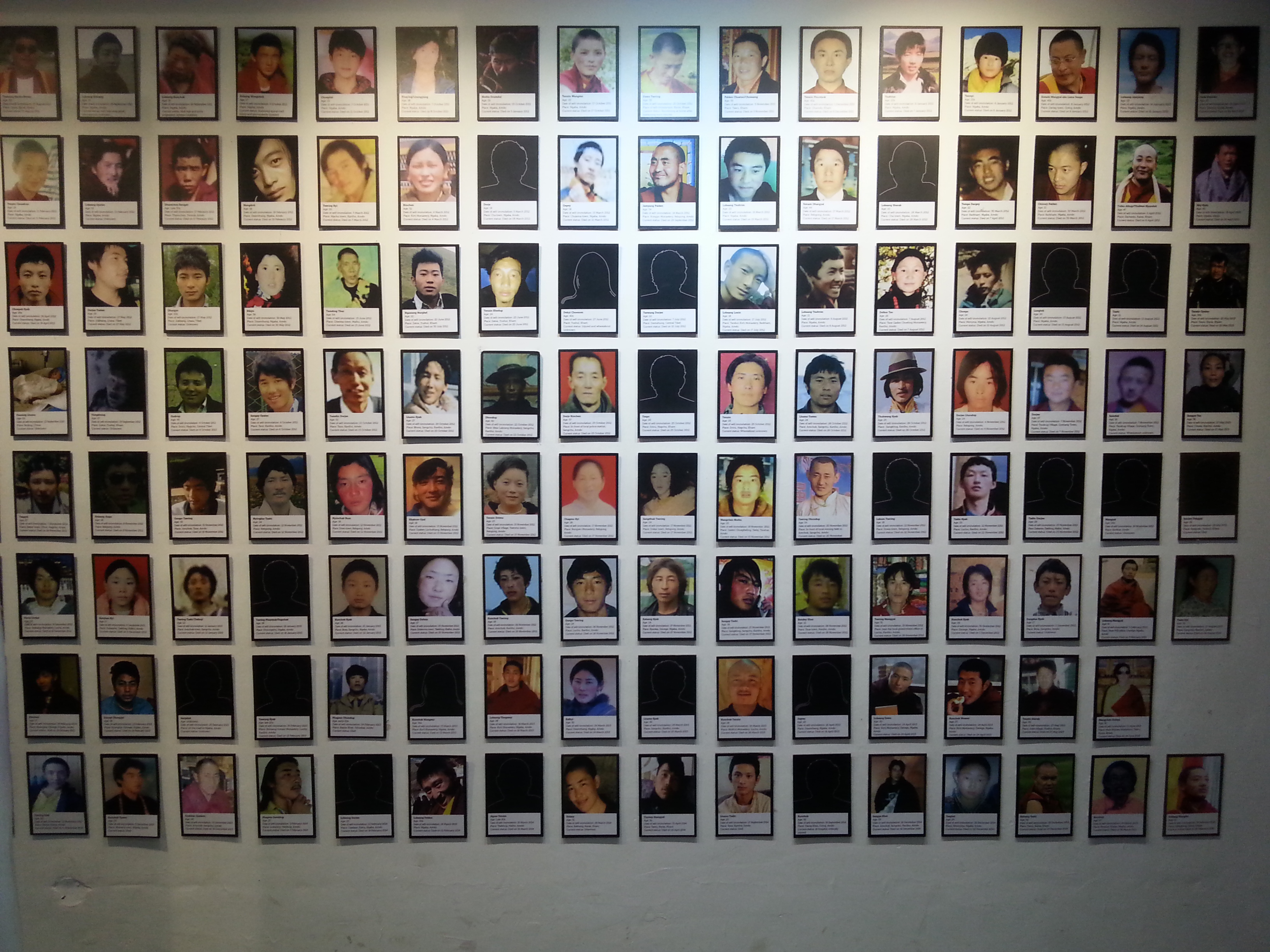

The CCP began its encroachment into the homeland of the Tibetan people in the late 1940s and by 1959, it had consolidated its takeover. Today, the region is one of the most heavily policed, militarised and surveilled places on the planet.

The last 70 years have seen Tibetan people and culture increasingly under attack. There has been an attempt to erase their system of religion and their language. A transmigration program has seen them relegated to second class citizens, while nomads have been forced off the land.

However, when the Trump administration passed Magnitsky style legislation last December to sanction China over its treatment of Tibetans, there were statements from progressive antiwar commentators attempting to understate the repression these people have long been subject to.

War is not the answer

The understanding of what is transpiring in Xinjiang in this article has been informed directly by the Uyghur people. It is evidenced in Beijing’s destruction of the centuries-old Uyghur section of the ancient city of Kashgar. It was not informed by western politicians like Bob Katter or Mike Pompeo.

“We can certainly fault conservative politicians in the way that they have approached this issue,” Brophy made clear. “We can also fault certain sections of the left to disregard or downplay the troubling aspects of domestic politics in China.”

The academic outlined that with the shift in global geopolitics and the decline of the “age of American unipolar dominance”, the “progressive wing of politics” needs to take an independent position to “combat unilateral western actions”, as well as “situations of injustice elsewhere”.

“What we need to be saying to people is not that there is nothing going on in domestic politics in China,” he concluded, “but there are better ways to provide solidarity with those people, rather than lend our support to Islamophobic western politicians.”