Attempted Murder of Refugee on Nauru Highlights the Failure of Government Policy

At around 11 pm on 9 February 2021, a car driven by a local ran down a Tamil refugee as he was riding a motorcycle on Nauru. The vehicle hit the back of the bike, knocking the Australian-held detainee off, and then it ran over the 36-year-old man.

The was car subsequently reversed back over his body, as part of an incident that’s now being described as attempted murder. The group of Nauruan occupants then got out of the vehicle and attacked the injured man, before stealing the motorcycle and fleeing the scene.

Nauruan police have since identified at least some of the occupants of the car. Two were allegedly men who work at an Australian-run refugee camp and know their victim. However, it remains unclear if these suspected assailants are still in custody or whether they’ve been charged.

The long-term offshore detainee – who’s been processed as a legitimate refugee – is now in the intensive care unit at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, after the government initially considered sending him to Fiji in an effort to keep him off the Australian mainland.

The brutal incident raises long recurring questions around our government continuing to commit gross human rights violations against innocent asylum seekers upon some distant neocolonial outpost in direct contravention of international laws that it’s long been a party to.

Tamil refugee in hospital after hit and run

Outsourcing human rights abuse

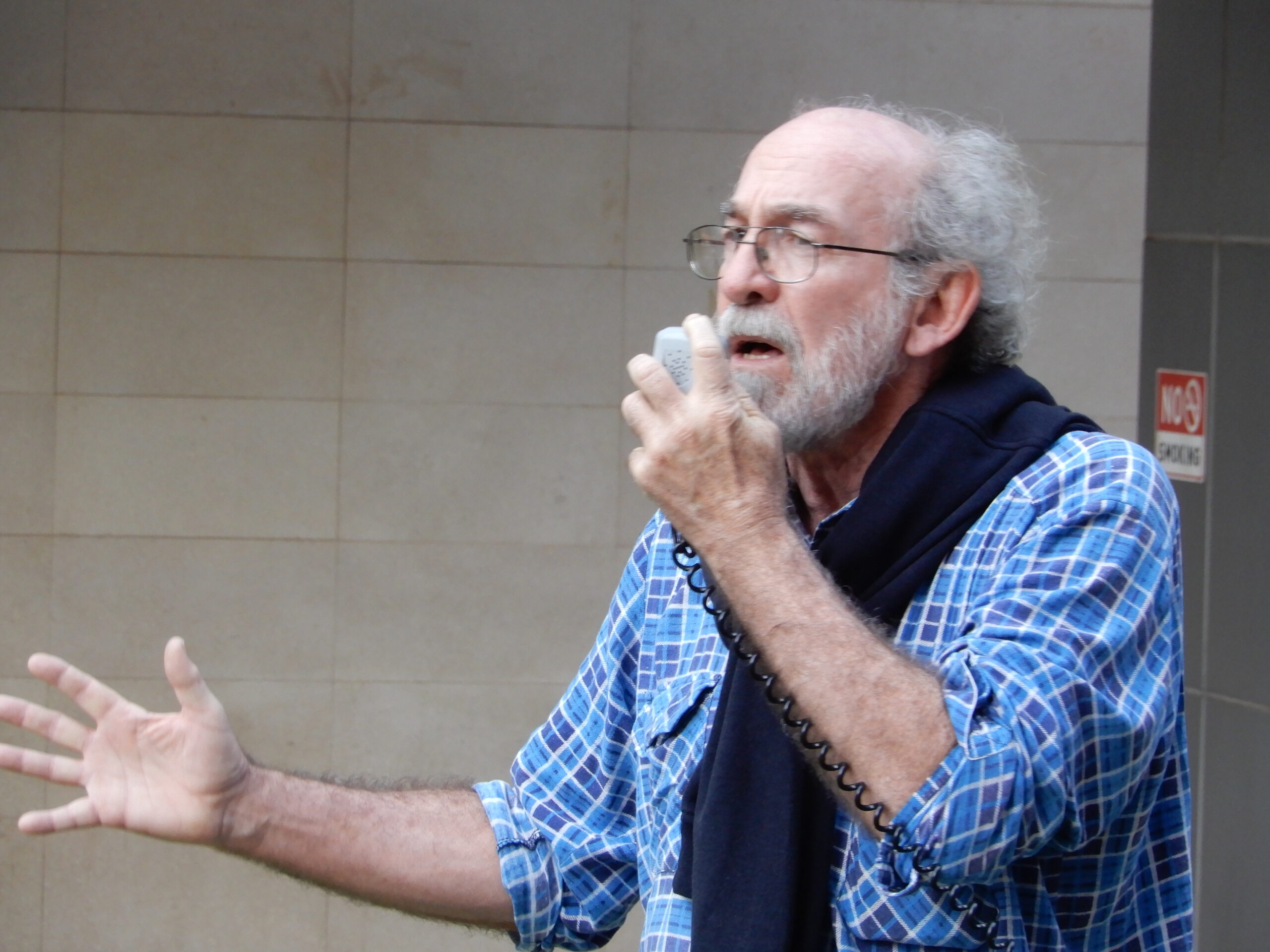

“It’s clear that it’s attempted murder. When they run someone over, back over him, then get out of the car and physically attack him. It’s hard to call it anything else,” said Refugee Action Coalition (RAC) spokesperson Ian Rintoul.

“It’s a shocking incident, but the greater tragedy is this is only the latest of a long history of very similar attacks,” he continued. “It has become routine for refugees on the road to be assaulted, bashed and robbed.”

The Australian immigration detention centre on Nauru was closed in 2019. These days, the 127 offshore refugee detainees remaining on the island live in refugee camps. AFR just revealed that Queensland firm Canstruct receives $10,000 a day per detainee to administer these facilities.

According to Rintoul, the “social reality” that has been created by the Australian government placing vulnerable asylum seekers and refugees on the poor island nation means detainees are afraid to leave their units, as they “are too frightened of the circumstances outside”.

“This is just a fact of life with the government placing refugees on Nauru,” he told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. This incident is “a direct result of the poverty on Nauru and the divisions that have been created by the Australian government”.

Profiteering in misery

The current Australian offshore detention regime on Nauru is the second such outsourcing of vulnerable people into dismal conditions both nations have been involved in. The first regime began in 2001 and came to a close six years later, while today’s dwindling program commenced in 2012.

At its height, in August 2014, the current regime saw 1,233 asylum seekers who arrived in Australian waters by boat detained on Nauru.

As to an idea of why this has been so disruptive, the Nauruan population is just over 12,500 people, while the island is tiny at only 21 square kilometres in size.

In 1980, Nauru was the wealthiest nation per capita on the planet. This occurred following the late 19th century discovery of phosphate deposits that were then mined. But when the resource run out in the early 80s, the wealth quickly dwindled. And today, Nauru is the 71st poorest nation on Earth.

Nauru gained independence from colonial ruler Germany in 1968. It then sought reparations from nations, like Australia, over the destruction of its natural environment via phosphate mining. Our nation begrudgingly paid in 1993, only after Nauru took it to the International Court of Justice.

The government of the small island nation agreed to the Australian offer to host its illegal offshore detention regime in 2012, as a way of boosting its economy.

Offshore detention was big business with Australia funnelling $3.4 billion to private contractors operating both Nauru and Manus Island immigration detention facilities in 2016.

Blood on its hands

Following the attempted murder of the Tamil refugee on Nauru last week, the Australian government took a moment to consider sending him to Fiji for treatment instead of bringing him over here, with the obvious issue being the man making it to the Australian mainland.

Issues with using overseas medical facilities to treat injured detainees have arisen in the past, often with dire consequences.

Take the case of Iranian refugee Omid Masoumali. After years of detention on Nauru, he doused himself in petrol and set himself on fire in front of UNHCR representatives.

Suicide is an option that many offshore detainees have attempted whilst in indefinite Australian detention.

This incident occurred in April 2016. But, as Masoumali was no longer held in the detention centre, but rather was living in a refugee camp on Nauru after being processed as a refugee, the Australian clinic could no longer administer care for him as it was only permitted to deal with asylum seekers.

With burns to 57 percent of his body, Omid was sent to the underequipped Nauruan hospital. This local facility couldn’t treat his injuries, although an Australian hospital is likely to have saved his life.

But due to the conditions on Nauru, it left a limited window of time to assess whether Masoumali needed to be evacuated immediately. So, he was left in the local hospital for an extended period, to be subsequently flown to Brisbane 30 hours later, where he went on to die in hospital.

Boat arrivals effectively settled

Under then immigration minister Scott Morrison, Australia launched Operation Sovereign Borders in September 2013. The policy was designed to ensure that asylum seekers arriving by boat would be incarcerated on poor foreign shores indefinitely without charge.

Sovereign Borders has been about successive Coalition governments being able to maintain the party line, which stipulates that no one arriving by boat in Australian waters seeking asylum will ever be settled in Australia.

However, this is a broken refrain as over 1,000 former offshore asylum-seeking detainees are currently living within the Australian community. And the number of these boat arrivals having been effectively settled in Australia is only growing.

This leads to the question as to why continue to detain just 127 refugees on Nauru and 140-odd in Papua New Guinea.

“It’s a political stance that they’ve been left with. Keeping Nauru open is because they’re absolutely determined that offshore detention is a part of their suite of refugee policies,” Rintoul made clear. These offshore detainees “remain a symbol of the policies that the government has implemented”.

“So, they’re very reluctant to be seen to do the right thing as far as the people who have been left behind are concerned,” he concluded. “They’re the final scapegoats of a failed and brutal policy.”