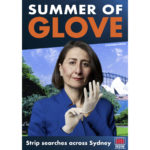

Berejiklian’s Drug Supply Regime Will Enhance Police Powers and Erode Individual Rights

Let’s face it, Gladys Berejiklian loves waging the war on drugs. When five young people died at NSW festivals over the summer of 2018/19, instead of implementing life-saving pill testing, she legislated for more ineffective prohibition laws, and attempted to close down the entire festival industry.

And this fondness the NSW premier has for the drug war is now leading her government to attempt to rush through the Drug Supply Prohibition Order Pilot Scheme Bill 2020 (the DSPO Bill), which currently has bipartisan support.

Introduced on 22 October, this legislation is especially dear to Gladys, it would seem, as it also allows her to partake in another one of her favourite pastimes, encroaching upon the civil liberties of those citizens living in the state she presides over.

The DSPO Bill would implement the two year trial of a program that involves placing an order upon people who’ve been convicted of drug supply or manufacture that allows them to be subjected to a form of enhanced police surveillance.

Sound a bit suspect? Well, NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge agrees. That’s why he’s been pulling out all the stops in an attempt to get Labor to withdraw its support, as not only does it constitute double punishment for those who’ve served their time, but it has implications for all NSW citizens.

Carte blanche powers

“At a time when the rest of the world is moving to curb excessive police powers, and the success of the Black Lives Matter movement, it’s just plain extraordinary that NSW Labor and the Coalition are moving to radically increase stop and search powers,” said Shoebridge.

“And they’re removing such things as reasonable suspicion from the test with this bill,” he added. “We are strongly opposed to this legislation.”

If passed, the two year DSPO pilot would be carried out in four NSW regions, with a view to rolling it out statewide in the future. These areas are Bankstown Police Area Command, Coffs-Clarence Police District, Hunter Valley Police District and Orana Mid-Western Police District.

Under the regime, an officer can apply for a DSPO if a target is over 18 and has been convicted of a “serious drug offence” within the last 10 years. The officer must also reasonably believe “the eligible person is likely to engage in the manufacture or supply of a prohibited drug”.

After an individual is placed on an order, NSW police officers are permitted to stop, detain and search a DSPO target without a warrant, along with entering and searching their premises or any vehicle they own. This can happen at any time under the order, which applies for at least 6 months.

“This is about the ongoing war on drugs,” Shoebridge told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “And the police seem to have persuaded the Coalition and Labor that if they just get more powers, and they just get more resources, that they will eventually be able to win this unwinnable war.”

A rush on enhanced powers

During his second reading speech on the bill, treasury secretary Scott Farlow told parliament that the “proposed DSPO model is based on the successful firearms prohibition order scheme”, which “prohibits a person from acquiring, possessing or using a firearm”.

Firearm prohibition orders (FPOs) have been around since 1973. They initially required police to obtain a warrant to search a target. However, since 2013, an enhanced FPO regime has been in play, which operates in a similar warrantless manner to the current drug supply prohibition proposal.

The NSW Ombudsman found that in the first 10 months of the warrantless FPO scheme, 642 searches were carried out, with no firearms being located. Over the initial 40 years of FPOs, 62 were issued, however after the powers were enhanced, more than 400 were issued within 12 months.

A hidden reach

“I don’t think there’s any doubt that the FPO legislation has had some success in disrupting some elements of organised crime,” Shoebridge continued. “But it is quite a different thing to move from legislation designed to deal with illegal firearms to legislation to deal with the war on drugs.”

“This is particularly as the definition used for a serious drug offence, includes deemed supply offences and therefore, has a very broad scope.”

DSPOs would relate to serious drug offences under the Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act 1985 (NSW) (the DMT). These include cultivation or supply of at least an indictable quantity of a prohibited plant, and manufacture or supply of at least an indictable amount of a prohibited drug.

So, ostensibly, this is about targeting manufacturers and suppliers. Mind you, the quantities involved capture both large-scale operations and small-time dealers. And as Shoebridge pointed out, the NSW deemed supply laws also mean the DSPO regime has implications for many more citizens.

Section 29 of the DMT provides that anyone found with more than a traffickable amount of an illegal drug is to be charged with supply, regardless of whether there’s proof of having provided it to anyone but themselves.

There are documented cases of individuals found with drugs for personal use being convicted via deemed supply and sent to prison.

Indeed, in practice, this law is more about penalising personal drug possession and small-time dealers, than any major crime figures.

So, at a time when ex-police commissioners, churches, law bodies and numerous civil society organisations are calling for drug decriminalisation, Berejiklian is implementing a rights-eroding surveillance regime that could impact people who aren’t even trying to turn a profit via drugs.

An incremental erosion

“The only effect this legislation will have is further increasing the march of police powers and their reach into people’s day-to-day lives,” Shoebridge maintained. “We’re seeing both the Coalition and Labor join together to remove some of our most fundamental and long-standing civil liberties.”

The Greens justice spokesperson had hoped to put the bill to an inquiry, but now that Labor has come on board, it looks as though it could be voted through both houses of parliament this week.

So, he’s calling on the public to contact Labor MPs and request they withdraw support.

The proposed DSPO and the FPO regimes aren’t the only programs that allow police to throw out the rulebook. The Suspect Targeting Management Plan (STMP) allows officers to subject targets to enhanced surveillance to prevent future crime, even upon individuals who’ve never been charged.

“The right to be free from arbitrary stop and search by police and the need for police either to satisfy a magistrate before they undertake a search or to have genuine and reasonable suspicion: all of these programs remove those fundamental rights,” Shoebridge concluded.

“The Greens will not – now or ever – support legislation that does that.”