Biosecurity Policing: The Securitisation of Public Health in the Pandemic Era

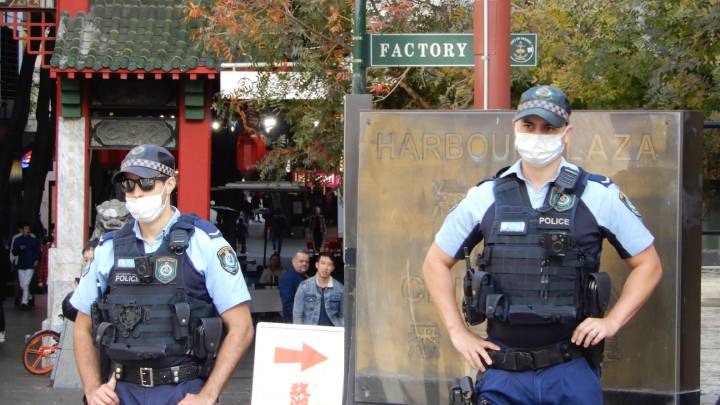

One of the most prominent aspects of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in this country has been an increased police presence on the streets, with officers enforcing an array of new biosecurity powers with gusto.

In the pandemic era, Australian police have been charged with a primary role in ensuring biosecurity, which involves measures being taken to minimise the risk of infectious disease.

Indeed, in NSW, police commissioner Mick Fuller was handed the reins to this state’s response early last year.

Biosecurity and public health legislation was enacted over the last decade at both the federal and state level, which bestows emergency powers upon the executive branch of government in the case of a health crisis that allows ministers to issue new laws without parliamentary oversight.

And rather than take a community-based approach to such crises, these legislative mechanisms facilitate a heavy-handed law enforcement tactic, which only serves to heighten pre-existing police bias.

This has been evidenced recently with the heavy deployment of NSW police to the less affluent multicultural areas of Sydney’s southwest once the COVID outbreak spread there, which followed a soft law enforcement presence when the virus initially broke in the city’s wealthy WASP east.

In a recent paper, a number of academics from Sydney and Melbourne argue that biosecurity policing “intensifies existing patterns of public order policing directed towards the ‘usual suspects’ and reinforces a criminalisation rather than a public health paradigm”.

COVID law enforcement

“Across Australia, the approach to policing COVID has been classic high visibility, public order policing based on enforcing breaches of new criminal offences largely through hefty fines, directions, searches but also arrest and charge,” said UNSW Faculty of Law senior lecturer Dr Vicki Sentas.

Along with four other academics, Sentas authored the Policing Biosecurity: Police Enforcement of Special Measures in New South Wales and Victoria During the COVID-19 Pandemic paper.

“The key question is whether policing is actually the best way to support public health objectives to stop the spread of the virus,” she told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “Our research indicates this form of policing creates its own social harms in taking a criminal justice approach to a complex health issue.”

The paper posits that COVID policing has involved “three interrelated sites of police power”: new criminal offences with high levels of discretionary application, enhanced powers of intervention or enforcement – think, compliance checks and go home orders – as well as regular police powers.

According to Sentas, COVID policing is a form of security policing, which is a preemptive military style of law enforcement that acts on threats “before they materialise”. And the ever-increasingly applied preemptive model heightens the prejudicial targeting of people based on race, class and gender.

“We saw this playing out in the very different ways that a paramilitary style mounted police presence in southwest Sydney could be contrasted with far less of a heavy presence at the height of the pandemic in the northern beaches or eastern suburbs,” the academic underscored.

The new norm?

The onset of biosecurity policing has dramatically altered the social landscape to the point that many ask whether it will ever be the same. A hangover effect was evident after Sydney’s 2020 lockdown ended, as police continued to enforce COVID measures long after in respect to public protests.

The offences that have been applied at the height of COVID outbreaks have been draconian. Currently, in Sydney, it is a criminal offence to be outside of one’s home without a reasonable excuse, as well as to be out in public without a mask on hand or in possession of proof of address.

“While the public health order offences are new, most of the police powers are not,” Sentas continued. “In many ways, policing under COVID has just amplified the old usual tendencies of overpolicing.”

Biosecurity policing has mainly involved officers issuing on-the-spot fines. Sentas notes this has disproportionately impacted First Nations peoples and lower socioeconomic communities. And she points out that fines have a heavier burden upon the less affluent.

As to the full implications of this new aspect to law enforcement, Sentas says there’s “a lot we don’t yet know” in terms of the proliferation of COVID-related searches and whether the pandemic has acted as a pretext to target the “usual suspects”.

Biosecurity search and seizure

Featured in the Current Issues in Criminal Justice journal, the Policing Biosecurity paper presents three key studies of the policing of COVID restrictions in NSW and Victoria in 2020, which include policing the streets, policing protests and the policing of public housing towers in Melbourne.

Sentas pointed to the policing the streets study, which involved NSW police data from the 3 months ending on 15 June last year, which showed that once an individual was stopped over a suspected COVID breach in this state, 45 percent were then searched.

And First Nations people are overrepresented in the statistics. While making up around 3 percent of the state population, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people accounted for 10 percent of those searched following a COVID stop, as well as 15 percent of those then arrested.

However, the data further revealed that almost 74 percent of First Nations people who were stopped for COVID reasons were subsequently searched, while, in comparison, only 63 percent of non-Indigenous people stopped were then searched.

“At an obvious level, surely searching people unnecessarily increases the risks of transmission,” Sentas reasoned. “This all raises a clash between public health objectives and the criminalisation model of policing.”

Militarising the response

The researchers concluded that the pandemic measures being enforced in Victoria and NSW last year were “exceptional”, and these measures were applied in a disproportionate way to communities that are already subjected to overpolicing.

But this didn’t have to be the way. “Stopping the spread of the virus needed a public health approach rather than the criminalisation path we went down with a heavy reliance on police powers,” Sentas advised. “There are genuinely other possibilities open to government.”

Assessments of the approach by authorities in the United Kingdom found that while the police in that country had played a part in its COVID response, that role was one confined to the margins and used as a last resort.

Yet, in NSW, rather than tone down the law enforcement approach, this week saw Australian Defence Force troops deployed to the communities in the city’s west and southwest that were already bearing the brunt of an enhanced police presence.

“With the call out of the military on the streets, some say that it’s just redeploying defence resources more effectively for a common good,” Sentas concluded.

“The problem with this argument is that it underplays the impacts of having the military on the streets doing governance work in a liberal democracy, especially for already overpoliced and marginalised people.