Black Lives Still Matter: Dunghutti Activist Paul Silva Puts Aboriginal Justice Back on the Agenda

At inception, NSW law enforcement had a focus on quelling First Nations resistance to British takeover of Indigenous land, and, over 230 years later, an excessive and overtly brutal focus on those who never ceded control to the Crown continues to be a key preoccupation of NSW police.

The Redfern Legal Centre released figures just last week that underscore the heightened focus the NSW Police Force takes towards First Nations, as, over the four years to June 2022, 45 percent of all state law enforcement use of force incidents involved Indigenous civilians.

That this figure is disproportionate in nature becomes all the more apparent, when taking into account that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living within the borders of NSW only make up 3.4 percent of the overall state populace.

And at a time when NSW police excessive use of force is being scrutinised, due to a string of lethal taserings and shootings since May, it must be remembered that the ease officers take to the application of physical force is much more laxed, when the recipient is an Indigenous individual.

The struggle for justice

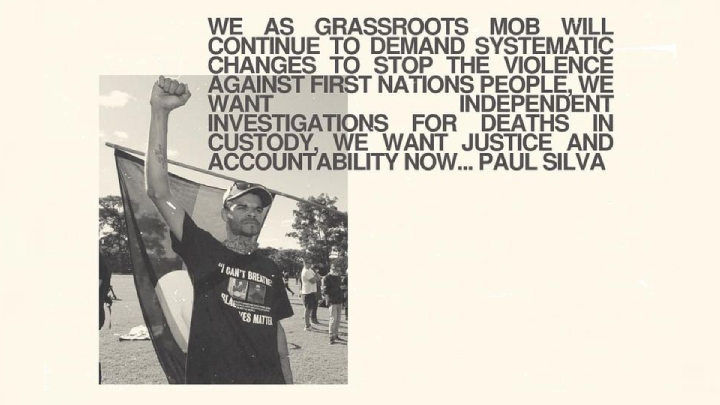

For almost a decade now, Dunghutti activist Paul Silva has been at the forefront of the struggle for First Nations people to have their rights upheld to the point that law enforcement and corrections can no longer brutally harm or even kill them with impunity.

Silva began campaigning for First Nations justice, after his uncle, 26-year-old Dunghutti man David Dungay Junior, had his life literally forced out of him by a group of specialist Long Bay prison guards, who were called upon to prevent the diabetic inmate from eating a packet of biscuits.

How this call led to the December 2015 death was captured on footage. After wrestling with Dungay and dragging him down a hallway, guards placed him on a bed face down in the prone position and five men then pressed upon his back, while he called out that he couldn’t breathe.

The resulting coronial inquest saw Corrective Services NSW apologise for “organisational failures” but no criminal charges were recommended by the state coroner.

Indeed, the Dungays have since protested, petitioned and campaigned the government, SafeWork NSW and the NSW Director of Prosecutions to reopen the case to investigate the correctional staff involved in Dungay’s death and prosecute them accordingly. Yet, all of this has come to no avail.

The movement continues

Over 2020-21, the BLM movement was at the fore in this state, as the community repeatedly rallied for an end to Black deaths in custody, as well as bringing a halt to the excessive use of force and surveillance NSW police has been subjecting the continent’s First Peoples to since the mid-1820s.

And with no actual progress having been made since 2020, but instead police use of force against First Nations having increased, Silva and other First Nations organisers are putting the BLM fight back on the agenda in this state with a series of rallies, commencing on 19 August in Sydney.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Black Lives Still Matter organiser Paul Silva about the ongoing need to rally against the violence of police, which is only escalating, and how this campaign is an extension of past efforts, with nothing to do with either side of the referendum debate.

The Black Lives Still Matter: Still Here, Still Fighting rally is being held at Sydney Town Hall on Saturday 19 August.

Paul, you’ve been at the forefront of the First Nations justice movement in this state for almost a decade now. You were involved in the prominent series of Black Lives Matter rallies held over 2020 and 2021.

So, what’s the significance of the “still” you’ve inserted into the renowned Black Lives Matter catchphrase? Why does the public need to be reminded that the BLM movement remains present and vital?

It’s important that First Nations mob and non-Indigenous people across Australia recognise that Black lives matter still. We had a massive turnout in 2020, where 50,000-plus people attended Town Hall in Sydney, despite police threats of arrest or fine.

We’re saying that Black lives still matter on a daily basis, because we’re under threat by NSW police and the government on a regular day.

The caption Black Lives Still Matter is to ensure that we, as grassroots mob, continue to take a stand on First Nations issues that continue to affect First Nations people across Australia.

The momentum of the BLM protests of a few years ago was overwhelming. The main target of the protests in this state was the NSW Police Force, which attempted to shut down a number of these demonstrations via the courts.

So, what’s happened since then? Is that momentum for change still there?

The momentum’s there. We’re always taking avenues to bring the government to the table on the issues surrounding Aboriginal deaths in custody, the forced removal of Indigenous kids throughout Australia, land rights and the destruction of sacred sites.

Just like the Black Lives Matter rallies of 2020, it is important that First Nations have a voice on these issues, and we need to be that voice for our people and for the families.

As a family member of a victim of a man who perished at the hands of correctional officers, it is very important for me and many other organisers to take a stand at this rally.

We’re calling out the wider community, non-Indigenous people across Australia – to take a stand with us, just like they did in 2020.

The 19 August rally will again be raising the issue of police brutality towards the First Peoples of this continent.

The Redfern Legal Centre last week released statistics, showing that over the four years to June 2020, 45 percent of all NSW police use of force incidents were directed towards Aboriginal people.

What are your thoughts on this still being the case in 2023, three years after the huge BLM protests of 2020?

Over the years since the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement, when we were highlighting police brutality against First Nations people, use of force statistics have dramatically risen.

This shows that the government and the NSW police organisation are not taking any drastic action toward these matters, which include brutalising Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people as well.

In my view, police brutality discriminates against First Nations people, but it also affects anyone officers come into contact with.

A prime example of this is the 95-year-old woman with dementia, Clare Nowland, who was recently tasered by a NSW police officer, which led to her death.

This shows that when NSW police officers wake up in the morning and put on a gun and a badge, they want to use that force and authority over people in the general public. And this is causing and inflicting dangerous injuries and death.

But the reality is releasing statistics is one thing and taking reform is another. And taking this reform is very important to myself and the other organisers of the upcoming event.

You’ve been campaigning against First Nations deaths in custody since your uncle, Dunghutti man David Dungay Junior, was killed by a group of specialist prison guards at Long Bay Gaol on 29 December 2015.

You’ve been fighting to see justice in the form of holding those involved in your uncle’s death criminally responsible.

But midway through 2023, and despite coronial inquiries, petitions and public campaigns, these individuals have not been held accountable.

So, what have these last year’s taught you about the Australian criminal justice system?

It’s a real eyeopener, going through all these processes and sitting through a coronial inquiry, as well as taking to the streets and demanding systematic changes and for criminal charges to be laid against the guards who killed David Dungay Junior.

There was an expectation from my family and all the organisers attending the rallies that justice would be brought. But this all landed on deaf ears. And the 2021 NSW parliamentary inquiry into these issues that developed out of the 2020 movement, also fell on deaf ears and blind eyes.

Back in 2021, I had to come to understand that we may never see justice for David Dungay Junior. No prison guard has currently been held accountable.

But I continue to be at the forefront of the movement, not just to make changes for my family, but for anyone else that’s going to be exposed to such treatment from the NSW police or Corrective Services NSW.

It’s important to me to work in my uncle’s legacy for those changes, as we haven’t received any justice or accountability over his death.

So, if I could assist another family or do something to prevent the next Aboriginal death in custody, that would be a bit of justice in my uncle’s legacy.

I’m passionate in moving forward that, despite my many years of action so far, one day, the government is going to listen – it will listen to the victims of these families that perish at the hands of officers.

Co-hosted by ACAR (USYD Autonomous Collective Against Racism), the Black Lives Still Matter rally is being held right in the middle of the Voice referendum campaign.

Why is this protest necessary when all this other organising is going on in regard to the Voice?

Prior to the Voice referendum coming around, we were here demanding change. We continue to make a stand. This rally is not about the Yes campaign or the No campaign.

This rally is purely about what we have been protesting to change for many years now, and that’s to change the systematic issues killing First Nations people right across Australia.

We were protesting back in 2020, prior to the referendum and the Voice to parliament being around. And we’ll be continuing to call for reform and justice, regardless of the outcome of the referendum.

Grassroots mob have an obligation to take a stand and to continue to call for change on systematic issues, especially changes to be made to police brutality and deaths in custody.

We were protesting and taking a stand prior to the Voice referendum ever being thought about.

And lastly, Paul, you’ll be marching through the streets of Sydney in a fortnight to raise the issue of the brutal and at times, lethal approach local law enforcement and corrections officers take towards First Nations peoples.

Why should people be joining the rally? And what are the broad changes you’re calling for?

People should be joining us in the fight to stop the brutality against people right across Australia. Tomorrow, it could be you or another 95-year-old woman.

This is a time for Australia to really take a stand and say, “Enough is enough. Stop the police brutality and implement independent investigations.”

Police should not be investigating police. It’s a conflict of interest on so many levels.

It is important that Indigenous people show up to make a stand. Their presence there is enough.

Non-Indigenous people and allies need to take a stand, whilst they’re aware that First Nations people are perishing at higher levels than any other nationalities in Australia.

In a fortnight, Saturday week, we’re going to be taking a stand on the streets, hopefully with the Sydney and western suburbs communities joining us, to fight for justice and accountability.

The demands for this protest are similar to those that we’ve been calling on for years: implement independent investigations, stop police brutality against people, which is causing grievous bodily harm or death. They’re pretty simple demands.

We want SafeWork NSW to conduct independent investigations for the coronial process to ensure that no workplace negligence has been involved in an incident.

As we know, a corrections centre or a police station is an employee’s workplace, so, therefore, these deaths should be inquired into via a workplace environment process.

We also call on the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) to conduct and conclude an independent investigation for criminal charges prior to the sitting of a coronial inquiry.

We know coronial inquiries are purely to find the cause of death and the circumstances surrounding it.

A coronial process is not there – in any way, shape or form – to hold anyone to account or punish them for their actions causing death.

So, we’re going to be out there protesting these deaths, and to stop the forced removal of Aboriginal kids from their families across Australia.

We see that on a daily basis: Aboriginal kids being removed from their homes, their parents and culture and put into a white family, where it’s not culturally appropriate or they’re then treated unfairly due to skin colour.

We also want to see the bulldozing and destruction of First Nations sacred sites across Australia brought to an end.

We want to be our own government and the authors of our own destiny. That is what we’re getting out there for on 19 August, and we’ll be back again after that.

We’re going to be continuously taking to the streets with our demands in order to put a stop to ongoing traumatising events that aren’t just affecting my family, but many families throughout Australia, both non-Indigenous and Indigenous.