Calls for Police Guns Out of First Nations Communities and an End to the Intervention

Karrinjarla Muwajarri-Ceasefire protesters gathered out front of Sydney Town Hall on 18 June, as part of a National Day of Action calling for guns out of remote First Nations communities and an end to the imposed settler colonial police state currently operating within them.

Launched by Warlpiri Elders from the remote Northern Territory community of Yuendumu, the Ceasefire campaign was sparked by the acquittal of police constable Zachary Rolfe over the 2019 murder of 19-year-old Warlpiri teen Kumanjayi Walker.

Standing before the Sydney rally, Gumbaynggirr Dunghutti Bundjalung woman Elizabeth Jarrett questioned how it can be that in 2022 armed police continue to patrol remote First Nations communities on their own land with military style weapons.

“Number four,” said Jarrett, reading from a list of demands, “an end to all discriminatory powers and laws introduced with the NT Intervention, including special police powers, compulsory income management, prohibition of consideration of customary law and others.”

Jarrett then explained that since the Howard government unleased the 2007 Intervention, the “special police powers” include “paperless arrests”, meaning NT police can take people into custody without accountability or any need to inform others that this has happened.

Yapakurlangu Warnkaru Matters

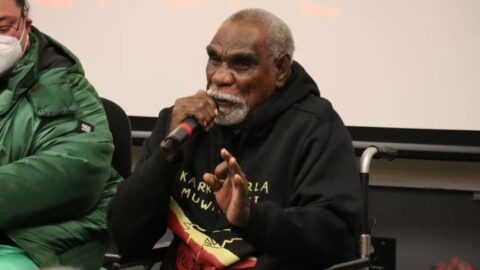

“We do not want guns in our remote community because it terrifies us. Our kids… walk around in fear,” said Yuendumu Warlpiri Elder Ned Jampijinpa Hargraves, who established the campaign in March. “We walk around in fear in our own community.”

“One of the things that we want is for police to put down their weapons and come clean, because it’s not their territory. It is not their place,” he told a Karrinjarla Muwajarri-Ceasefire forum at Sydney’s UTS on 10 June. “If you want to walk around with guns, you do it in your own community.”

With the support of civil society organisations across the country, the National Day of Action saw protests held in centres nationwide, including Mparntwe-Alice Springs and at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. These called for an end to guns in remote communities and the NT Intervention.

The shooting death of Kumanjayi Walker is a direct outcome of the federal intervention that today continues to see heavily armed police – some of whom have served in the army overseas – patrolling communities in a manner that sees locals treated like a foreign enemy.

“We are sick and tired. Our loves ones are gone. Why the shooting started and where? It was the Coniston Massacre,” Hargraves added, referring to the NT police sanctioned and perpetrated mass killing of First Nations peoples, including the Warlpiri, in the region where he’s from in 1928.

A racially discriminatory policy

The Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) had to be suspended so the government could launch the NT Intervention in June 2007, which saw the deployment of the army to remote Aboriginal communities. The operation was justified by claims that were later proven fraudulent.

The Liberal Nationals Intervention policy was presided over by the Rudd Labor government once it took office in late 2007. And the Gillard government then replaced the initial laws with the Stronger Futures for the Northern Territory Act 2012 (Cth), which secured a further decade of intervention.

However, that Act has a sunset clause, with some of its measures set to expire on 29 June this year, while the majority of the laws come to an end on 16 July. This means that the Albanese government will have to deliberate upon whether to simply let this discriminatory policy pass or to continue it.

UTS Jumbunna Institute senior researcher Paddy Gibson told Saturday’s rally that the government “seized control of community lands… sacked town councils and put white managers in charge”. It further “built compounds with barbed wire fences around them” and “took the assets away”.

“There were 7,500 jobs at the time within the communities with the Community Development Employment Projects. It didn’t pay good wages. But it was a job,” Gibson continued. “All those people were sacked, and they put them on Centrelink to control their income with a BasicsCard.”

The non-Indigenous academic also outlined during the UTS forum that the Intervention has meant police were gifted with “the extraordinary power to enter anyone’s house without a warrant” in remote Aboriginal communities, along with being provided “huge amounts of funding”.

Settler colonial justice

In March, an all-non-Indigenous jury acquitted Zachary Rolfe of the November 2019 murder of Kumanjayi Walker. The NT police constable had served time as an Australian military officer in Afghanistan before moving on to law enforcement.

Nineteen-year-old Walker was shot whilst being held down by Rolfe’s partner in a family home the officers had entered without a warrant. NT police were looking for the teenager as he’d breached the conditions of a suspended sentence so he could attend a funeral in Yuendumu.

“They were in sorry business when the police stormed their house and took this young man’s life,” Jarrett made clear on Saturday. “Now we get to see Zachary Rolfe published and platformed as a glorified police officer.”

The Rolfe murder trial was a chance for the nation to correct its stance on Aboriginal deaths in custody by making a law enforcement agent accountable for such a death.

Yet, instead, he was set free and the NT government then allocated more funding for the policing of remote communities in May.

Ceasefire now

Paul Silva addressed the rally just before it marched through the Sydney CBD to the NSW Supreme Court.

The Dunghutti man lost his uncle, David Dungay Junior, to a death in custody in December 2015, when a group of Long Bay Gaol guards held him facedown whilst he couldn’t breathe.

The ardent activist called upon the Albanese government to bring the Intervention to an end, which includes the system of heavily armed police patrolling unarmed Aboriginal communities and led to the death of Kumanjayi.

“How hard is it to have a ceasefire order on remote communities?” Silva asked. “Our elders on those communities still live like they did when the First Fleet arrived. But you’ve got cops walking around with AR-15s and Glocks threatening and intimidating the First Nations people.”

“That is unacceptable.”