Can Obtaining Another’s Consent Be Used as a Murder Defence?

Just a few weeks short of Halloween in 1996, 35-year-old Sharon Lopatka left her home in Maryland USA, leaving her husband a note which simply read:

If my body is never retrieved, don’t worry: know that I’m at peace

Lopatka had found herself going to some dark corners of the internet, meeting a man named Robert “Bobby” Glass and requesting the unthinkable.

She had shared with Glass a sexual fantasy of meeting a man and being “tortured until death”.

Her body was found soon after she left her home, with Glass having strangled her to death (seemingly with her consent).

Glass ultimately pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and was sentenced to just over six years’imprisonment.

The case raises an intriguing question: is consent ever a defence to murder?

The offence of murder in New South Wales

Murder is an offence under section 18 of the Crimes Act 1900, which applies where a person causes the death of another person by way of voluntary act or omission with either:

- An intention to kill or inflict grievous bodily harm; or

- With recklessness indifferent to human life; or

- During or immediately after the commission of an offence (known as ‘constructive murder’).

The maximum penalty for intentional or reckless murder is life imprisonment.

The maximum penalty for constructive murder is 25 years imprisonment.

If the elements of murder are not present, a person may still be prosecuted for either voluntary or involuntary manslaughter.

Can obtaining consent amount to a defence to murder?

The short answer is: there is a general rule that obtaining another person’s consent to being killed cannot be used as a defence to murder.

There are, however, extremely limited exceptions to this rule in the context of voluntary assisted dying.

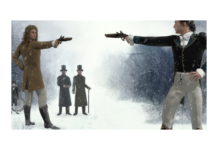

The earliest clarification of the the issue regarding whether a person can consent to being killed centred on various ‘duelling’ related killings which came to trial in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

A ‘duel’ is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched weapons. Duels with swords were common in the 17th and early 18th century in England, with pistols becoming the duelling weapon of choice in the late 18th century.

In R v Rice 1803 3 East 581, the Court of the King’s Bench clarified that a dueller who inflicts a fatal wound as part of a duel was guilty of murder, whether he was the challenger or not, and regardless of the fact that the deceased willingly took the risk.

This made it clear that consent is no defence to homicide related charges.

More recent decisions, such as R v Brown, have made it clear that consent is equally no defence to non-lethal forms of violence, such as the consensual assault of another resulting in actual bodily harm.

However, there are exceptions to this general rule, such as where this occurs during regulated sport as well as for medical or hygienic purposes.

Offences of aiding, abetting, inciting or counselling suicide

Assisting a person in ending the life may also give rise to offence related to assisting the suicide of another.

Section 31C of the Crimes Act 1900 outlines two offences relating to the aiding and abetting or inciting or counselling the suicide of another.

An offence exists under section 31C(1) if a person aids or abets the suicide or attempted suicide of another person. This offence carries a maximum penalty of 10 years imprisonment.

An offence also exists under section 31C(2) if a person incites or counsels another person to commit suicide, and that other person commits, or attempts to commit, suicide as a consequence of that incitement or counsel.

This offence carries a maximum penalty of 5 years imprisonment.

Assisted Dying Laws

On the 19th of May 2022, New South Wales passed the Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2022 which allows eligible people the choice to access voluntary assisted dying from the 28th of November this year.

Voluntary assisted dying means an eligible person can ask for medical help to end their life.

The person must be in the late stages of an advanced disease, illness or medical condition.

They must also be experiencing suffering they find unbearable.

If a person meets all the criteria and the steps set out in the law are followed, they can take or be given a voluntary assisted dying substance to bring about their death at a time they choose.

The substance must be prescribed by a doctor who is eligible to provide voluntary assisted dying services.

However, it’s important to note that this exception exists in a very narrow set of circumstances and the general principle that a person cannot consent to their own killing still largely applies.