Canberra Abandons West Papua at Jakarta War Talks: An Interview With AWPA’s Joe Collins

Foreign affairs minister Marise Payne and defence minister Peter Dutton set off last week on a “let’s get ready for war with China” diplomatic tour, with the first stop being Jakarta, where they met with their local Indonesian counterparts.

The two nations renewed their defence pact, and the decision was taken to strengthen joint efforts on terrorism and cybersecurity.

But no official mention was made of Indonesia’s operations in West Papua, which have escalated since late 2018.

This is despite Jakarta having officially labelled West Papuan freedom fighters as terrorists and separatists in April. Indeed, since 1963, Indonesia has occupied the Melanesian country, brutally suppressing its Indigenous population and having killed an estimated half a million locals.

And with the ministers from each nation agreeing to increase the level of training Canberra provides Indonesian troops, it can be readily expected that, as in the past, this guidance from Australian war forces will be directly impacting upon the misery of the West Papuan people.

Fitting counterparts

Dutton gifted Indonesian defence minister Prabowo Subianto with 15 Bushmaster military vehicles on 9 September.

Defence company Thales Australia has been selling these tank-like vehicles, which it manufactures in this country, to Jakarta since late 2013.

Indonesian president Joko Widodo appointed Prabowo to the position of defence minister in October 2019.

The former chief of the nation’s notorious special forces group Kopassus, Prabowo used to be banned from entering the US due to his long list of documented human rights abuses.

Self-determination rising

The UN handed over the region of West Papua to Indonesia in the early 1960s. And despite a caveat that Jakarta must hold a referendum to allow West Papuans to decide on the question of self-government, what followed was a small group being coerced into voting to stay with Indonesia.

But the ever-present West Papuan independence movement has been gaining momentum over recent years.

The UN Human Rights Council was presented with the West Papuan People’s Petition in early 2019, which contains 1.8 million signatures calling for a real referendum. This accounted for 70 percent of the Indigenous population risking their lives to partake in the campaign.

A West Papuan provisional government was set up in exile in January this year, with long-term independence leader Benny Wenda announced as its interim president. While at the same time, the Netherlands became the 83rd nation to call on the UN to enter the region to evaluate the situation.

And in May, the West Papuan provisional government announced that it had established a presence on the ground within West Papua itself, with twelve government departments having been set up and ministers appointed to oversee each of the portfolios.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Australia West Papua Association (AWPA) secretary Joe Collins about the implications of the recent diplomatic visit to Jakarta, the situation with West Papuan political prisoners, and why people are now stating its likely West Papua will be free.

Australian foreign minister Marise Payne and defence minister Peter Dutton meet on 9 September with their counterparts in Indonesia to hold bilateral talks around joint training operations, terrorism and cybersecurity.

Joe, you’ve raised an issue over Canberra’s security partnership with Jakarta specifically because of what’s been taking place in West Papua. So, broadly speaking, what’s the issue?

You can look at the issue in West Papua from many angles. Some see it as a straight up human rights issue, where others see it as a self-determination struggle.

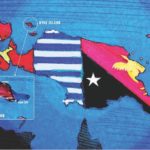

In 1963, Indonesian took over official administration of the territory of West Papua, which was the former Netherlands colony of Dutch New Guinea: the whole of the western side of the island of New Guinea.

This was after a short administration period under the UN, about seven months.

The Dutch were preparing West Papua for independence. But the first Indonesian president Sukarno claimed that West Papua should be part of the new Indonesia. And in the end, he basically received the backing of the UN.

The Dutch and the Indonesians signed the 1962 New York agreement, which said that the Netherlands had to leave, hand West Papua over to a short period under the UN, which would then hand it over to Indonesian administration.

When the Indonesians took over in 1963, the human rights abuses began. And they have been ongoing ever since.

This is one of Australia’s nearest neighbours. It’s 58 years since the takeover, and West Papuans are still marching in the streets risking arrest and torture.

If you look at the banners they carry, it says it all: We are not Indonesian. We are Melanesian. We want to be free. We want a real referendum.

The referendum they’re referring to is the so-called Act of Free Choice that took place in 1969. Only 1,026 West Papuans were chosen to vote on self-determination under the point of a gun. So, they were forced to integrate with Indonesia.

West Papuans call this the Act of No Choice.

Australia and Indonesia last week renewed their existing defence pact, which will now see Jakarta’s troops increasingly training at ADF facilities. Australia has already been involved in training Indonesia’s troops and police officers.

Can you talk on how Australia’s training has been and will likely impact?

Australia has been training the Indonesian military for a long time. If you go back to the occupation of East Timor by Jakarta, activists were calling on Canberra to break all ties with the Indonesian military because of the abuses there.

Even former foreign affairs minister Gareth Evans said at the time, he thought we were training the military, but we were actually training human rights abusers.

So, it’s not unusual for Australia to be training the Indonesian military. But what’s going to happen now is there will be an increase in military training. There will be more joint exercises, in particular naval exercises.

If you look at the bigger picture, this has got to do with what some people see as the expansion of China. Australia would like to see Indonesia as a partner in trying to contain China.

A key point at last week’s meeting was a commitment to tackling terrorism in the region. However, since April, Jakarta has been referring to West Papuan freedom fighters as terrorists.

Will this enhanced focus on terrorism impact West Papua?

First of all, the OPM (the Free Papua Movement) is not a terrorist organisation. Even a former Indonesian general said this was a counterproductive move as they’re not terrorists.

But what it really does is that every West Papuan who attends a rally or demonstration could – at the whim of an Indonesian security force person – be classed as a terrorist, arrested and charged with terrorism.

The West Papuan people’s civil society organisations have condemned this labelling. If Jakarta was trying to show that it had the West Papuan people’s benefit at heart, this is not the way you go about it.

It also means that security forces are able to have more of a heavy-handed approach to West Papuan rallies and demonstrations.

We trained Indonesia’s Detachment 88, which is a counterterrorism police force. It formed after the Bali Bombings. But any government that has such a special force will always use them in an area where they feel there is an insurgency going on.

The media keeps calling what is going on in West Papua a low-level insurgency. And now that they’re claiming the West Papuans are terrorists it’s more likely that they will start using special forces troops there.

Dutton said our nation will be providing Indonesian defence minister Prabowo Subianto with 15 Bushmaster military vehicles. What’s your take on this arrangement?

They say that they will be used by Indonesia in UN peacekeeping operations. But I see it more that Australia is hoping to sell military equipment to Indonesia going into the future, along with having Jakarta help Australia to counter China.

Last week, you raised a few cases regarding West Papuan political prisoners that are of particular concern. What do they involve?

There’s the arrest and imprisonment of Victor Yeimo, who is an international spokesperson for the KNPB (the West Papuan National Committee). He is a real high-profile activist.

The KNPB has had great success with getting large numbers of people out on the streets for rallies and demonstrations. So, security forces target in particular the KNPB. That is why Victor was arrested and charged with treason.

The arrest was over what they call the West Papua Uprising of 2019. He is supposed to have instigated it.

Victor has been gaoled. Both his mental and physical health were deteriorating. They have finally taken him to hospital after being reluctant to do so. It seems his health is getting better, but he will still be charged with treason.

This is a peaceful activist. They are trying to intimidate the KNPB to stop coming out in such large numbers and bringing the world’s attention to what is going on in West Papua.

There are a large number of West Papuan political prisoners. Most of them are gaoled for peaceful activism – nothing to do with armed conflict. But Indonesia tries to stop any attention being given to what is taking place in West Papua.

Of course, with our special relationship with Indonesia, Australia should be urging Jakarta to release all West Papuan political prisoners.

West Papuan provisional government interim president Benny Wenda warned last week that the displacement of villagers due to Indonesian military operations continues, with 2,400 villagers having recently fled their homes in Maybrat Regency.

What do you understand to be happening there?

This last week, the OPM attacked a security post. The military immediately said we will hunt down those responsible, which scares villagers in the region, as they know what happens during military operations: houses get burned, animals are killed, and food stores are destroyed.

These villagers will literally face starvation in order to avoid the Indonesian military. There is a total lack of trust between the military and the West Papuan people, so they naturally flee their operations.

This distrust spills over into other areas, such as COVID-19. By the end of July, there were just over 50,000 cases of COVID in West Papua, and 1,000 deaths had occurred.

West Papuans are reluctant to be vaccinated, not because they have hesitancy about the vaccine, but because medical teams are accompanied by the military or it’s the military doing the vaccinations.

They are so fearful of the Indonesian military that they prefer not to be vaccinated. And this distrust between the West Papuan people and the military is at all levels of society.

We put in a submission to DFAT, when the HIV/AIDS epidemic was going on up there, and we said we should be helping train the West Papuan people in health and nursing.

That’s a progressive way we could be helping the West Papuans. It’s understood that it’s a sensitive issue with Indonesia. But it is a way that we could actually be helping them, so they could become health workers and do their own vaccinations.

And lastly, Joe, recent years have seen a strengthening of the West Papuan freedom movement, with an interim government formed, which includes a presence both in exile and on the ground.

As well, parts of the West Papuan armed forces have unified, and the West Papuan People’s Petition was released.

How do you foresee this positive resurgence in the movement developing?

This is really terrific. The West Papuans have been accused in the past of not being united or vague in their plans.

But with the formation of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP), there is a real groundswell of support, particularly in the Pacific region.

West Papua is on the agenda of the two regional organisations: the Pacific Island Forum and the Melanesian Spearhead Group.

Just recently the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States has written to the UN asking that they send a fact-finding mission to West Papua. Pacific leaders are continuously raising West Papua at the UN.

So, there is a significant groundswell of support within these countries for West Papuan people. This is a worry for Jakarta.

In the joint Australian and Indonesian press release, Jakarta said it would work with Australia in the Pacific region. This is really to do with West Papua.

Jakarta is fearful about how much progress West Papua is having and the support it’s getting in the Pacific region. So, they’ve been establishing bilateral aid negotiations with Pacific Island countries, which is to try and stop the support for West Papua at the UN.

But it’s not going to happen. The West Papuans are making great progress all around the world. They’re better educated. They have more university students.

During the dark days of Suharto, people would ask whether West Papua will ever be independent, and you might be a bit hesitant to say so.

But now, there’s so much progress going on that people might say it’s a given that one day West Papua will achieve its right to self-determination.