Collaery Prosecution Dropped, But Politicians Remain Unaccountable for Bugging Timor Cabinet

In December 2013, ACT barrister Bernard Collaery was at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague set to represent Timor-Leste against Australia, when ASIO raided his Canberra home, along with that of former spy Witness K, who was about to testify as a key witness in the proceedings.

The case involved the Howard government having bugged the Timor-Leste cabinet offices in order to gain advantage in oil and gas treaty negotiations, which was an operation that Witness K, then an ASIS agent, had been charged with overseeing in 2004.

On the advice of the Inspector General of Intelligence and Security, K consulted ASIS-approved lawyer Collaery in 2008 in regard to a work dispute. And on his learning of the bugging, Collaery, a long-time supporter of East Timor, determined the surveillance operation had been illegal.

Then federal attorney general George Brandis authorised the 2013 raids, which were designed to shut down the ability of K and Collaery to pursue the matter in the international arena. And with the ASIO searches having achieved their aim, Brandis then dropped the matter.

Yet, for reasons never clearly established, Brandis’ successor AG Christian Porter greenlighted the prosecutions of Collaery and K in June 2018, and he further applied never before used national security orders to bury parts of the evidence, not only from the public, but also from the accused.

Prosecution dropped

The Collaery prosecution dragged on, costing taxpayers millions, while the case became increasingly Kafkaesque as the AG’s department attempted to slap mounting secrecy provisions upon proceedings to the point that the Canberra lawyer couldn’t view key trial evidence.

Fortunately, on 7 July, incoming Labor attorney general Mark Dreyfus announced his government was dropping the prosecution, four years after it had commenced, and a year after Witness K decided to end his ongoing saga by pleading guilty to conspiring to reveal classified information.

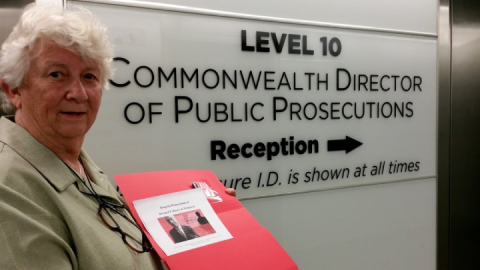

However, whilst welcoming the end of the prosecution, Sister Susan Connelly, one of Collaery’s most prominent supporters, asserts that Timor Sea matters are far from over, and she recommends, as do others, a Royal Commission into the Timor-Leste bugging and surrounding issues.

Yet to be resolved

A member of the Timor Sea Justice Forum, Sister Connelly has been intimately linked to the East Timor independence movement since the 1990s, as has Collaery. And she makes clear that to attempt to dupe one of the poorest nations on Earth out of treaty profits is our country’s shame.

The sister recently authored East Timor, René Girard and Neocolonial Violence, in which she argues that Australia scapegoated the East Timorese nation, which had been a vital ally during the last world war, in an attempt to maintain its own regional security and shore up fossil fuel profits.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Sister Susan Connelly about the decision to pursue Collaery and Witness K years later, her experiences in Timor-Leste which make the charges against our nation graver, and the issues that now need to be resolved post political prosecutions.

A fortnight ago, attorney general Mark Dreyfus dropped the prosecution Bernard Collaery. As one of the ACT barrister’s most prominent supporters, you’ve welcomed the outcome.

But, Sister Connelly, how should we consider the decision the Australian government made in mid-2018 to pursue a case that had been left alone for years prior?

Honestly, that is one of the imponderables of the century. I’ve been thinking, why on Earth any government, or anybody with half a brain, would undertake this prosecution, when the whole thing could have been history?

In March 2018, when the border was signed, it was a new and genuinely fairer border for Timor. We had a fairly happy Timorese government and an Australian population that could be relied upon to put any talk of the spying down to another bad political decision.

But the prosecution that took so long, four years, and was so expensive to the Australian taxpayer, and is now discontinued, has been a huge own goal by the government. It’s a perfect example of government shooting themselves in the foot.

It’s connected to revenge. It was a case of revenge. It was throwing the whole weight of the Australian administration behind the protection of previous occupants of high positions.

Namely, Alexander Downer, who became a lobbyist for Woodside, and possibly John Howard. But we don’t know to what extent the proper processes were followed in authorising the spying.

Apart from being revenge, it was also planned as an exercise in deterrence, lest any other intelligence officer or his or her lawyer would have an attack of conscience. And it’s probably a very powerful message to other people: don’t you dare.

There must have been some sort of calculation as to the risk of charging Collaery and K. George Brandis didn’t do it. It was only when Christian Porter came in.

Perhaps they assessed that the deterrence factor outweighed the damage that the inevitable focus on the government spying would bring.

But, in actual fact, it has made Australia appear like a total fool internationally. And it has also weakened public trust in the organs of government to provide the fairness that’s expected of legal processes.

I don’t trust it anymore. I no longer trust that decisions made at that level can be made without scrutiny.

So, the decision to pursue the prosecutions has served to shine a spotlight on the spying operation.

Absolutely. Who would have remembered it? We’re talking almost 20 years ago. But there has been so much focus, although not from the main organs of the media, except for Four Corners and a few ABC programs.

In terms of the lack of scrutiny from the Herald and also the Murdoch press, talk about a dereliction of journalistic duties. I’ve told the Herald that a few times.

There have been two editorials from the Herald over the last few years, so editorially, they’ve been on the side of Bernard Collaery, but it’s just been the minimal amount of inches in their paper really.

Over the decades, you’ve travelled to Timor-Leste to work with the local people on numerous occasions. And from your experiences, you state that our nation should be ashamed of itself for having sought to undercut the newly independent nation in oil and gas negotiations.

Can you expand on why this is the case?

I’ve been to Timor at least 40 times from 1996. I’ve been back and forth, raising money for our programs here, which were in health and education for Timor.

I was with a group that developed the very first literacy program in the Tetum language, which is what we were asked for. It’s a wonderful program and it formed the basis of the government’s curriculum up there.

I’ve seen firsthand the hovels that people lived in, with tiny little children with bellies and small arms: a perfect indication of malnutrition.

The other day I was looking at a new report from the World Bank this June, saying that while things have improved to a great extent, still 5 percent of children under the age of 5 do not reach their fifth birthday.

They die because there is not enough food, and the food is poor. And that has a huge effect on adult health and on education. We knew that. You just cannot teach hungry children.

This is 2022. Imagine what it was like 18 years ago, when we were spying on East Timor. They have improved. The numbers are there. Their life expectancy has gone up.

But at the time that Australia was spying, they’d just come out of this terrible oppression, where people had died of starvation. Right through Timor’s history, there is a whole history of starvation.

East Timor was invaded by Indonesia in 1975, right after it had gained independence from Portugal. This led to a decades-long conflict, with local group Fretilin fighting for self-determination.

In the 1990s, the campaign to free East Timor was prominent in this country, and Collaery and yourself were well-known members of the movement.

Can you remind us of what was happening at that time, and why it was such an important grassroots campaign?

It’s more correct to say the Portuguese walked out on the Timorese. They left an illiteracy rate of 98 percent in 1974. That was after 500 years of colonisation.

It’s absolutely appalling. They purposefully only educated 2 percent of the population, so they could keep the bureaucracy going.

One of the big things that changed and was the catalyst for me finding out about Timor, was that Indonesia opened Timor in 1989.

Before then, you couldn’t get in or out over the 14 years since the invasion. They just closed it. It’s a bit like West Papua now.

It’s interesting that in that same year 1989, in December that year, that Gareth Evans, then our foreign minister, signed a deal with Ali Alatas, the foreign minister of Indonesia, splitting a portion of the Timor Sea for resources 50-50. So, there’s links there already.

Therefore, people were able to get in. But one of the most significant things is that, as people were able to get in, the memories of World War Two were stirred. And I don’t believe they’ve been stirred enough.

At least 40,000 Timorese died violently in World War Two as a direct result of their assistance to 700 Australian soldiers. It makes my flesh creep.

Where is it in the school curriculum? The War Memorial is a right off. Many people don’t know about it. I believe it’s being kept from us, because why would governments support the Indonesia occupation and, at the same time, recognise the huge sacrifice those people made?

We hold our war memories strongly as Australians. You only have to look at Anzac Day. But for something like this to have happened, if the Americans had lost 40,000 or New Zealanders, there would be a monument in every town and a holiday every year. But the Timorese aren’t even mentioned.

They could have sided with the Japanese, like the people in West Timor did. But the East Timorese stuck to the Australians to the great sorrow and guilt of many Australian men that I knew, like Alan Luby, Gordon Hart and Paddy Kenneally.

Paddy said, “All we’ve brought to these people is misery.” And Gordon Hart said to me, “The only people I can’t look in the eyes are the Timorese”.

These are the people we turned on. When people found out about it that’s where the grassroots campaign came from: this sense of fairness. And hundreds of thousands have supported them, just unfortunately, not the government.

You’ve already touched upon this, but two decades after it gained independence, how would you say the Southeast Asian nation of Timor-Leste is progressing today?

Actually, they’re not doing too badly, as nations go. Twenty years is not a long time. They still remain the poorest nation in Southeast Asia. But they have coped with COVID fairly well.

Unfortunately, the prices of everything have gone up because of the war on Ukraine. It’s not just us that are paying more, they’re paying more.

They are having a go. But the big things are health and education. There is improvement. But had they not had to spend so much time, expertise and money in opposing Australia over this oil business, they would have probably been a lot better off.

Back to the Collaery and Witness K prosecutions, it’s repeatedly been remarked that those reporting a crime were being punished by the authorities, while those who perpetrated the crimes were being left off the hook.

Can you speak on this point?

Of course, spying is not a crime on our statute books, because it’s a tool of government. But, in effect, it is a criminal act because it flows from the disordered human actions like greed, stealing and deceit. It’s immoral, and that’s where criminality comes from.

The amount of planning is extraordinary. The execution of this spying just didn’t happen overnight. So, there are lots of people who should be held to account.

They had to plan it. They had to disguise it under a humanitarian program. They had to get the signal out to a ship in Dili, so they had to have all the equipment there. They involved the Australian Embassy in Dili. Somebody had to translate it all. So, there is a hell of a lot of work going on there.

A lot of people have a lot to answer for. But Alexander Downer is the main one because he was the foreign minister. So, he would have had to give the go-ahead for it.

And lastly, Sister Connelly, you’re a member of the Timor Sea Justice Forum. It stresses that with the dropping of the Collaery case, “the Timor Sea matters have not been resolved”. The members of the forum have been following this for decades.

So, what does the forum consider as the way forward on the Timor Sea matters?

There are a few things we want to do. We are having a meeting this Friday. So, we will be making decisions then about how we’re going into the future. But in general, there are certain areas that we’re going to be talking about.

The first one is there must be an investigation into the spying. It was a total overreach of government power.

So, an investigation not only into the spying, but into the whole association with Timor over the resources of the Timor Sea, because there are big questions about other areas, which we have gained billions from.

Laminaria-Corallina is one of them. Another one is the important matter of the helium that we have already benefited from. Helium is so valuable. But with the helium in the Laminaria-Corallina, nobody got to profit except the oil company.

And the definition of petroleum was changed to leave helium out.

Another thing we’re concerned about is Witness K. What is going to happen to him?

The other one that we are asking lawyers about is what’s going to happen to all the documents that have been used in the 73 hearings so far. Who has control of those? What legislation governs the protection of those types of documents?

That’s in looking forward to some judicial inquiry that might happen or, in my preference, a full-blown Royal Commission into the whole Timor Sea matter.

But of course, I want to be talking to my own people about that, and the areas here, of which we will support.