Dunghutti Activist Paul Silva Calls on Albanese to “Step Up” on Deaths in Custody

“It’s appalling that it’s continuing, and no one is calling it out for what it is: the murder of First Nations people,” said rights activist Paul Silva. “Hopefully, Albanese can step up, take into account these events and recognise what’s going on in custody with First Nations people.”

“Many people are not even found guilty of a crime – they’re in there on remand – and they are still coming home in a body bag,” he underscored.

Silva’s uncle 26-year-old Dunghutti man David Dungay Junior was killed in late 2015 by specialist prison guards in the hospital ward at Long Bay Gaol, after five of them pressed down on his back as they held him face down on a bed, while he repeatedly called out that he couldn’t breathe.

A 2019 coronial inquiry resulted in no disciplinary action taken against the guards, let alone suggestions of a criminal investigation. Then Corrective Services NSW commissioner Peter Severin simply issued an apology to the Dungay family for “the organisational failures at the time”.

The Dungays have been uncompromising in their pursuit of justice, which has included repeated requests to the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions and SafeWork NSW to criminally investigate, with NSW barrister Phillip Boulten SC having provided advice on the potential for charges to be laid.

This all happened under a Coalition government. Silva is now calling on the new Labor government to follow through on its mood for change aspirations and translate them into deep structural reform that prevents deaths in the custody of authorities prior to their happening.

There is a war

Unlike its predecessor, the Albanese government has been quite vocal on proposals to transform the plight of the continent’s First Peoples, whether that be with calls for a referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament, the inclusion of flags at press conferences, or promises to end racist programs.

Right now, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are amongst the most incarcerated on the planet. They comprise 31 percent of the Australian adult prisoner population, whilst only accounting for less than 3 percent of the populace living on the continent.

First Nations custodial deaths have continued under both Coalition and Labor governments. The Hawke government established the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, which delivered 339 recommendations in 1991. These set out a comprehensive blueprint for change.

But most of the recommendations remain unacted upon, and around 500 Indigenous deaths in custody have transpired since. Last year marked the 30th anniversary of the inquiry’s final report, yet 17 First Nations people lost their lives in the custody of either police or corrections in 2021.

And not one police officer or prison guard has ever been convicted over an Aboriginal death in custody.

Indeed, the acquittal of NT police constable Zachary Rolfe over the close range shooting death of Kumanjayi Walker – two shoots to the side of his torso whilst the 19-year-old Warlpiri teen was held down by the officer’s partner – highlighted the state of Indigenous affairs in this country.

Taking it to the United Nations

“The Australian government fails families of Aboriginal deaths in custody in a number of ways,” Silva told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “They don’t investigate appropriately to get answers and hold those accountable for the brutalisation and the deaths of First Nations people.”

“Numerous inquests have changed a number of policies and procedures, but that hasn’t stopped the deaths,” he continued. “There needs to be criminal investigations, with disciplinary action taken and accountability towards the people involved. We won’t see change until that happens.”

Silva and the rest of the Dungay family have to come to terms with the fact that despite their efforts, and the show of support the wider community displayed towards their cause in 2020 with the upsurge in the Black Lives Matter movement, the Australian system may never serve justice.

So, in June last year, David’s mother Aunty Leetona Dungay announced at NSW parliament that she was taking the case to the United Nations Human Rights Commission, with a legal team that includes renowned Australian human rights barristers Geoffrey Robertson and Jennifer Robinson.

We’ve had to go to the UN to shame the Australian government and show how basic human rights are being denied when it comes to its actions towards First Nations people,” Silva explained, adding that it might not bring justice for David, but it has the potential to prevent further deaths in custody.

Ending the war

There’s no doubt that the Albanese government has prioritised Indigenous affairs in its first fortnight far further than the Coalition ever did over its near decade in office, including with the appointment of Linda Burney to cabinet, which marks the first Aboriginal woman in a ministerial role.

The new Wiradjuri minister for Aboriginal affairs has announced the government will be moving to scrap the racist CDP work-for-the-dole scheme, abolish the cashless debit card and provide funding to the families of victims of deaths in custody to participate in coronial inquests.

But according to Silva, “it’s one thing to say and another thing to do”, and he wants to “see those words put into action”.

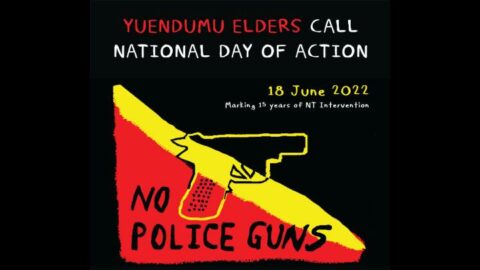

Following the acquittal of NT police officer Rolfe over the charge of murder for the killing of Kumanjayi Walker, the Elders from the town of Yuendumu, where the Warlpiri teen lived, have commenced a campaign to see police guns removed from remote Aboriginal communities.

A National Day of Action is being held on 18 June, which will serve to highlight that at present Australian police equipped with military-style weapons are patrolling these unarmed First Nations communities on their own land.

The Warlpiri Elders assert that these issues have escalated since the Howard government unleashed the 2007 NT Intervention, which also led to the cashless debit card. And they further point out that it was federal Labor that went on to reinforce these measures with its 2012 Stronger Futures Act.

Silva underlined the importance of the campaign to see guns out of remote communities and he outlined that he’s since reconciled the fact that his family may never obtain justice for his uncle under the Australian system, but the Dungays are now focused on the UN later this year.

“Unfortunately, I do not see this as getting any justice for David Dungay, but it may prevent these events from occurring going into the future,” the Dunghutti man said in conclusion. “And that’s what I really want to see.”