Dunghutti Activist Paul Silva Calls on Wider NSW to Protest Record Custody Deaths

The NSW criminal justice system is killing more First Nations people than ever before. A total of 16 Indigenous people of various ethnicities died in the custody of either NSW police or Corrective Services NSW in 2021, which is the most since such records began being kept in 1995.

This is horrific on multiple levels: not only that so many preventable deaths occurred in state custody from a fraction of the population or that it occurred in a nation that often asserts its human rights credentials, but it happened on the 30th anniversary of the release of the Royal Commission report.

NSW state coroner Teresa O’Sullivan broke the news two weeks back. She added that this marked a doubling of the previous highest death rate, which was eight in 1998. And she further made clear that these aren’t simply figures, they’re real people, who leave behind traumatised families.

First Nations people accounted for 37 percent of the deaths in the custody of this state’s police and corrections agencies last year. Yet, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people only make up around 3 percent of the overall NSW populace.

“They say accident. We say murder”

There are a number of factors fuelling First Nations deaths in custody, but the bottom line is the racist culture that’s permitted to pervade the NSW Police Force and Corrective Services NSW, which includes what appears to be a sanctioned brutality when dealing with Indigenous peoples.

Aboriginal teens get run down by police cars. Aboriginal men quietly get shot in living rooms. Aboriginal inmates get repeatedly ignored when crying out for help in prison cells during health emergencies that prove fatal. Some get chased into rivers to drown.

The fastest growing group of people in NSW correctional centres, and indeed, facilities nationwide, are First Nations women. BOCSAR reported that over the six years to 2017, the number of Aboriginal women inmates in this state rose by 74 percent. These steep increases continue.

And when Aboriginal people die in police custody there is never any accountability or justice.

The footage of David Dungay Junior’s death shows five prison guards pressing their body weight onto his back whilst holding him face down on a prison bed in December 2015, as he calls out repeatedly that he can’t breathe, until he never does again.

Despite the footage, the usual outcome was forthcoming, nothing happened to the killers.

A constant struggle against Australian oppression

In taking the top job, O’Sullivan has vowed to make First Nations deaths in custody a priority. She’s the coroner who brought a halt to the 2020 inquest into Wiradjuri man Dwayne Johnstone, who was shot in the back by a prison officer whilst cuffed and shackled.

The NSW Director of Public Prosecutions followed O’Sullivan’s lead and charged the prison officer with manslaughter and has since upgraded the charge to murder this year. All these acts are unprecedented in NSW.

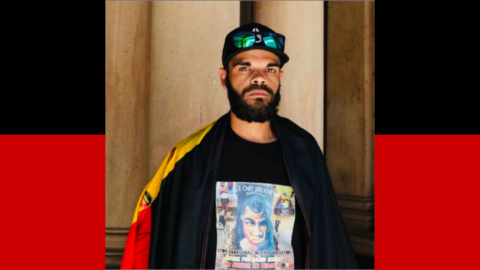

But Dunghutti rights activist Paul Silva wants to see the DPP involved in inquiring into all First Nations deaths in custody, so serious contemplation of criminal charges is the norm, after he had to endure having his uncle David Dungay killed in Long Bay.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Silva, who’s helping organise the Warrang-Sydney Record Number of Black Deaths in Custody rally on 22 October, to discuss why it’s important that the broader NSW community get out on the streets and join First Nations people in calling for an end to this crisis.

NSW State Coroner Teresa O’Sullivan recently announced that last year saw the largest number of First Nations deaths in custody occur in this state.

Paul, you’ve been at the forefront of the campaign against Aboriginal custodial deaths over recent years. So, how was it to hear this considering the attention that’s been drawn to the crisis?

It shows that the current government, and what was implemented from the NSW parliamentary inquiry and in the Royal Commission hasn’t worked.

Deaths have doubled last year. The statistics show that. The state coroner recognised ongoing deaths in custody, which is a massive step for her to take.

But it’s one thing to recognise, and another thing to take action, like sitting with the families, demanding systematic change, and justice and accountability for the deaths that have happened.

With the attention given to an American white cop murdering George Floyd in mid-2020, First Nations people here took the opportunity to shine a light on local deaths in custody. And there was a groundswell of support.

The focus on deaths in custody was maintained last year, as it was the 30th anniversary of the handing down of the Royal Commission recommendations.

So, given that deaths in custody have featured prominently in the public eye lately, how would you describe the response of the federal and state governments to the crisis?

Federal and state governments have been sitting there twiddling their thumbs and laughing at these events, in my view. They have been called out, and called on to take a stand, by the families to make those changes.

But they’ve decided to sit there and let it fall on deaf ears and blind eyes, because they’re part of the colonial system, which they continue to run.

The Albanese government has come to power making a concerted show of recognising First Nations people and prioritising the establishment of a voice to parliament.

What do you think about the new government’s approach to Indigenous affairs, especially in light of this recent figure?

The way the current government is interacting with First Nations people is going against Aboriginal protocol. They’re not reaching out to grassroots people, who are at the forefront and have gone through these traumatic events.

A voice to parliament really isn’t going to change anything. We’ve demanded this from government on numerous occasions. Not just my family, but many other families over the years.

They’ve sat down and demanded it. They’ve written to numerous governments, whether it’s been the Morrison government or the Albanese or Gladys Berejiklian.

We’ve called out to these people. We’ve cried out for their help. And it’s still falling on deaf ears. Basically, the voice to parliament is not going to be a voice unless action and accountability is taken.

It’s one thing to put a voice in there, but is that voice going to be grassroots people, who are going to be passionate about fighting for justice and change for First Nations, and not just someone sitting back, being in the role to benefit themselves?

You need people who are really going to help community, people who are going to help people in remote communities and remote Country, because we definitely need it.

We need more Aboriginal politicians. We need more Aboriginal MPs. In my view, the voice to parliament is not the right way to take steps because they’re just saying and not doing.

We’ve suffered NSW parliamentary inquiries. We’ve suffered through inquests. We’ve demanded justice and accountability. We’ve taken to the streets. We have constantly taken to the streets. We are constantly putting out demands. We are constantly putting out petitions.

So, when is this system going to give justice and accountability to First Nations people? It’s going to be an ongoing battle long into the future, as far as I can see with the current government.

It wouldn’t take much for the Albanese government to bring it to parliament’s attention. It doesn’t take much for him to demand the Director of Public Prosecutions to investigate independently.

For Christ’s sake, SafeWork NSW doesn’t even investigate them, despite these deaths taking place in a workplace environment. These people are employed by the NSW government.

They would investigate a finger getting cut off at a worksite, but they won’t investigate someone screaming that they can’t breathe or an allegation of a suicide in custody.

The Albanese government is pushing for an Indigenous voice in parliament. But would you say the issue of Aboriginal deaths in custody itself is often ignored or not even approached?

Exactly. It’s been seen in parliamentary inquiries that when issues arise about these deaths, many people walk out and don’t want to listen.

These events fall on deaf ears and blind eyes because the normal person in society and the people in the government live a high life and they believe that these people are criminals and bad people.

Well, in reality, they’re really not.

Most people who have died in custody haven’t even been found criminally guilty of their crime. They are sitting in there on remand, not even having been found guilty in a NSW court, and they die in there.

This just shows the corruption and systematic racism throughout the government, the gaols and throughout the court system.

It shows how everything that the government has access to is built against First Nations people. There’s nothing that we benefit from that the government has implemented, other than ongoing trauma.

Everything they implement gives ongoing trauma.

They bought the Aboriginal flag. Now, they say everyone owns the Aboriginal flag, including the everyday Australian citizen. So, that means a non-Indigenous person can now say, “I own the Aboriginal flag.”

Well, in my view, and with Aboriginal protocols, that doesn’t make sense. That’s not okay.

The government is saying it’s going to implement a voice to parliament, well, when it comes to deaths in custody and any other issues that this voice speaks on, I can almost guarantee that PMs and politicians are going to walk out.

They won’t want to hear about it, because they believe that those people are bad.

The killing of your uncle, David Dungay Junior, at the hands of five specialist guards at Long Bay Goal in December 2015 led you to take a prominent role in the deaths in custody resistance movement.

But David’s death, with the accompanying graphic footage of it, didn’t really gain the attention it warranted until an African American man was killed on the other side of the world.

What does this tell us about the overall attitude of white Australia to the First Peoples of this continent?

It took something in the USA to cause wider Australia to attend rallies and protests in regard to deaths in custody.

It’s so sad that events outside of Australia have to happen before the people in our own backyard recognise what the First Nations people deal with here on a daily basis.

Our family and many other families have marched in the streets with ten to 40 people. So, to then attend a rally and have 50,000 people behind you screaming out justice for numerous amounts of family members was just amazing.

But we need that at every event. People need to show up, speak up and stand up, because, like I’ve said, deaths in custody have doubled and that’s a jump since the NSW parliamentary inquiry.

So, that shows that didn’t work. And we know the Royal Commission back in 91 didn’t work. And it’s just continuously happening on a monthly basis, with at least four deaths in custody.

It’s not in the mainstream media. It’s not even spoken about in the community. And family members are traumatised from these actions, and nothing really happens.

So, in your opinion, what needs to be done here?

We need an independent investigation from the Director of Public Prosecutions or an inquiry from SafeWork NSW. They’re the main two points.

Those demands are not just my personal demands. They’re also the demands of many other families: to implement that the DPP investigates, alongside the coroner, independently for any criminal action and that SafeWork does too.

And lastly, Paul, as you pointed out, the Black Deaths in Custody rally in June 2020 was massive.

Right now, you’re helping organise the Record Number of Black Deaths rally set to take place at Sydney Town Hall on 22 October.

So, what would you say to those people who made the effort in 2020, but perhaps haven’t done so since? Why should the broader community be out on the streets demonstrating?

They should be out there standing beside First Nations people helping them in their fight for systematic change not just within the governments but within the prison systems and police stations, and with how police interact with the everyday public.

This is an event that people need to attend like they did in 2020. They need to get up and speak out about this, because the everyday Australian experiences this in one way or another from the authorities.

So, now is the chance to get out and support First Nations people and come and take a stand on 22 October at midday.

It is a good opportunity to stand with the First Nations people if you haven’t before. You can get an insight and listen to those family members and the ongoing trauma that they suffer, and the ongoing battle that they are up against demanding accountability and justice from the government.

They’ll get an insight of how systematic racism works, and how people are thrown in gaol and not even found guilty by a NSW Court but they still come home in a body bag.

Now, that does not make sense to me in any way shape or form, and it shouldn’t make sense to any other human being.

It’s a good time to take a stand, and say, enough is enough, and recognise the ongoing trauma. And to really recognise what has happened since 2020, which is nothing.

So, now is the time to come back bigger and better, to make sure that the new government knows that we’re not going away. We are not standing down.

We are not stopping until there is an independent investigation implemented by the DPP or SafeWork.