Dutton Is Turfing Vulnerable Refugees Out Onto the Street Mid-Pandemic

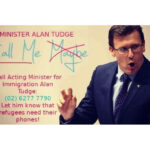

Dutton and his new acting henchman Alan Tudge have come to the decision that the current pandemic and downturn in the economic climate is a good time to start evicting asylum seekers and refugees out of their long-term accommodation, and cutting off their financial support.

As the @HomeSafeWithUs coalition outlines last week a number of refugees and asylum seekers were notified of this coming change in circumstance, which could ultimately affect up to 845 individuals, including 284 children.

Brought into play in August 2017, this policy involves notifying refugees and asylum seekers held in onshore community detention – with no right to work – that they will be turfed out of their housing in two weeks’ time, with their income support being cut off in three weeks.

These refugees and asylum seekers were either brought to Australia from offshore immigration detention to undergo medical treatment prior to the commencement of Medevac in February 2019, or they’re part of the legacy caseload, which are people who arrived by boat in either 2012 or 2013.

Indeed, right now, many refugees and asylum seekers already in the community on temporary visas have lost their employment due to the COVID crisis, and they’re not eligible for pandemic income support.

So, Dutton’s seen fit to throw these other community detainees into this current economic wasteland, with no real rental or employment record.

Final departure visas

“This is creating fear and insecurity. The hope is that some people will agree to go home,” explained @HomeSafeWithUs spokesperson Pamela Curr. “The trouble is that they can’t go home. Many people come from countries that wouldn’t accept them back.”

“These people’s cases go back seven years and sometimes more,” she told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “They’re required to go and find somewhere to live, when they’ve got no record of renting anything in Australia, no income and no rights to Centrelink.”

As Curr tells it, community detention has been an ongoing legal limbo for these people, with the federal government not having decided what should happen to them. So, the state’s current solution is to push them out onto the street and see what happens.

In a practical sense, this involves placing these “illegal maritime arrivals” on a bridging visa E (BVE), which grants working rights and can be valid for three to six months.

Back in mid-2017, these visas were termed “final departure bridging E visas”, which clearly expressed government intentions.

“Many of these refugees on bridging visas rely on community groups for housing and food to save them from total destitution,” Curr advised. And she added that the latest group transferred out of community detention “have little prospect of gaining employment in the COVID recession”.

The true con artist

Dutton announced the BVE policy on 28 August 2017, when he told the Daily Telegraph that an initial 70 asylum seekers would have their income cut off within a fortnight and they’d also lose their long-term accommodation after three weeks.

The home affairs minister spruiked the heartless policy using his usual technique: demonise the victim.

According to Dutton, offshore detainees were running a medical scam to make their way to the mainland to live in rent-free accommodation and obtaining a better deal than pensioners.

These people were permitted to come to Australia to seek treatment but were then using “tricky legal moves” to prevent being sent back to indefinite detention, Dutton claimed. “This con has been going on for years,” he added.

Initially, the government only saw fit to throw single refugees out onto the streets, however by May the following year, the department confirmed that a further 100 individuals were being served notices, which included families with children under 18 years of age.

Cruel policy

Ms Curr recalled that she’d been in contact with a couple of young single Somali women living in Brisbane, who were served with BVE documents. This gave them no choice but to sleep in a car that a friend was kind enough to park in the driveway of the house they were evicted from.

The women were able to camp in the car for five nights, and when they needed to use a bathroom, a fellow asylum seeker still living in community detention allowed them to use hers. That was until the friend’s flatmate notified the authorities as to what was going on.

“So, the immigration department told this woman that if she let her friends use the toilet or the shower, they would re-detain her,” the long-term refugee rights advocate continued. “That was the way it was being dealt with.”

Release them into the community

The @HomeSafeWithUs coalition is comprised of 20 refugee advocacy groups that have been organising accommodation to house another cohort of offshore detainees that were brought to Australia last year under the now revoked Medevac laws.

The 180-odd men are being detained in Melbourne’s Mantra Hotel and Brisbane’s Kangaroo Point Central Hotel. However, with the onset of the pandemic the government has simply left them in this accommodation, without any means to properly protect themselves or room to socially distance.

These detainees have compromised health, making them extra vulnerable to COVID-19. Whilst they’ve been languishing in the hotels, a staff member at each location has tested positive for the virus. And the department carried out thorough security checks on all of them before they came out.

“What we propose doing is to offer the government an option other than the continued detention of those people who’ve been brought over from Nauru and Manus under Medevac,” Ms Curr made clear.

People have offered beds to accommodate the refugees held in hotels and also those in centres.

Prolonged and indefinite

While much of the public is aware that the government has been detaining certain refugees and asylum seekers for over seven years now, Ms Curr explains that advocates have located some people in the onshore detention system that have been there for over a decade.

And then there are others who have been positively assessed as refugees but are still detained in immigration centres. Curr explains that the Migration Act now permits the minister to have the final word on anyone’s release, regardless of any ruling from the tribunal or the court.

“We want a fair process, not this business of shoving applications in the bottom draw and not processing them,” Ms Curr concluded. “People arrived here in 2013 to seek asylum, they’ve lodged an application and they haven’t even had an interview from the department.”