Emojis Inside the Courtroom

Think the small expressive image at the end of your text or Facebook post is just an adornment? Well the law may think otherwise. Courts have found emojis to be relevant as evidence in a wide range of cases. In fact, the improper use of the miniatures has landed a number of people on the wrong side of the law.

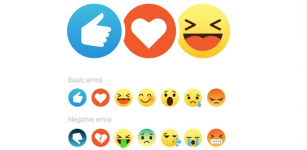

They started as a bit of a fad, but over time emojis have become a widely used in digital communications. Figures suggest that around nine million Australians use emojis regularly. You can download apps that provide access to hundreds of the small, sometimes-cute images.

Emojis have even been the subject of research papers, one of which concluded that using them can make others view you as less competent in the workplace.

They’ve been the topic of media headlines – you may recall coverage of Julie Bishop describing Vladimir Putin with an angry faced emoji. Or the tweets during last year’s leaders’ debate when many of Malcolm Turnbull’s responses attracted large numbers of the ‘poop’ emoji.

No longer just an adjunct, or a joke or ornament to add humour or make a point, emojis are increasingly recognised as a legitimate part of our online interactions. It’s fair to say they’ve even become a staple of our digital landscape. But more than this, the interpretation of their meaning has been debated in courts across the globe.

Court cases involving emojis

The challenge for lawyers is to persuasively convey the meaning of emojis to magistrates, judges and indeed juries, in accordance with the instructions of their clients.

In some instances, the meaning can be relatively straightforward. For example, a judge in New Zealand recently sent a man to prison for stalking his ex-partner after using an aeroplane emoji at the end of a Facebook message to her.

The message said “You’re going to fucking get it ✈”. The court found that the emoji amplified the man’s threat, and ultimately sentenced him to 8 months in prison.

This is certainly not the only case whereby emojis have contributed to the seriousness of a person’s conduct. In France, a man threatened his girlfriend via a text message ending with an emoji of a gun. The court found that the emoji was sufficient to establish the offence of “death threat in the form of an image” and the man was sentenced to six months’ in prison and given a €1,000 fine.

But sometimes, the meaning is not so clear or easy to establish. In the US, a high school student was charged with computer harassment and threatening school staff after posting several messages to her Instagram account, combining text with emojis of a gun, knife and a bomb. She claimed the emojis were a joke and were never intended as a threat.

Determining the meaning

Commentators say that most of those prosecuted over the use of messages containing emojis are under the age of 30, which suggests that younger age categories are communicating differently to older generations in the digital age.

While emails, text messages and social media posts have long been used in courts of law, evidence containing emojis is being relied upon more frequently – by prosecutors, plaintiffs, respondents and defendants alike.

Although emojis often express sentiment, courts may find it difficult to interpret their precise meaning in the absence of additional information such as descriptive words, body language, tone of voice and gestures. The overall context of communications between the parties can therefore become particularly relevant for determining whether messages are meant to be taken literally, ironically, sarcastically or otherwise.

In the outlined New Zealand stalking case, the man purchased air tickets the day after sending the message containing the aeroplane emoji – which provided further evidence of intent. But other cases may not be as easy to decipher.

As the law continues to grapple with changes in communicative technologies, there will almost certainly be new case law and perhaps even legislation to help courts deal with developments in digital interactions. Gifs too, while perhaps slightly easier to decipher than the simple emoji symbols, will no doubt also make their way into courts of law.