Enhanced COVID Policing Is Fast Becoming the New Norm

“What we have seen in the last six months, in particular, is a ramping up of police hostility towards peaceful assemblies that goes far beyond anything I’ve seen in the last ten years,” Brisbane City councillor for the Gabba Ward Jonathan Sri said on Tuesday.

The Greens councillor was referring to the actions taken over recent months by the Queensland Police Service in cracking down on demonstrations, especially those involving young people protesting for the release of former offshore asylum-seeking detainees being held in a city hotel.

Sri understands this escalation in policing firsthand. He told Sydney Criminal Lawyers that officers recently turned up at his house at 1 am, serving him with an order to attend court seven hours later over a protest he wasn’t involved in, while in June, he was arrested at a rally under false pretences.

The heavy-handed policing of the Brisbane refugee protesters hasn’t been confined to Sri. Six demonstrators were arrested at an action last Saturday, a woman was taken into custody for causing security guards anxiety, and officers haven’t been shy about wrestling activists into submission.

But while Sri states this escalation in policing is an anomaly looking back over the last decade in Brisbane, it’s no deviation from the way that police forces nationwide are currently turning up the volume since COVD-19 appeared. And this certainly isn’t confined to busting up protests.

Choked into resistance

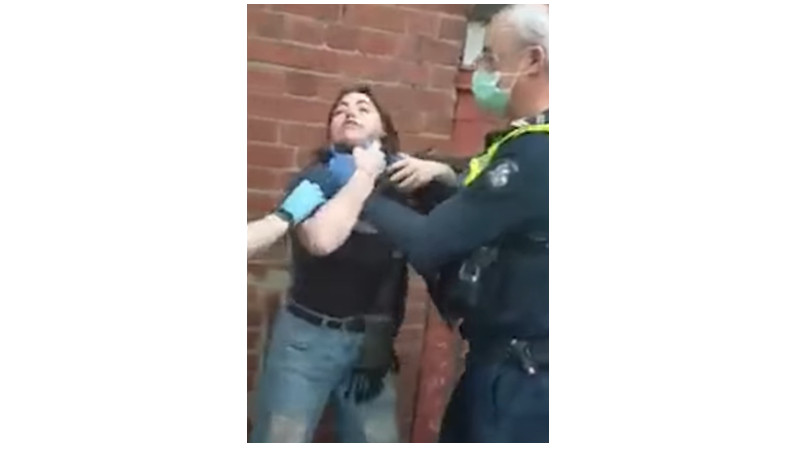

An image of a Victoria police officer choking a woman in Collingwood as she wasn’t wearing a mask appeared online last week. Although hard to believe at first, the footage shows the older man dragging the young woman along by the throat, before tripping her over and kneeling down on her.

The video reveals an officer emboldened by the recent broadening of police powers, as he enjoys the use of excessive force a little too much. Then the police had the gall to stick the woman in a van, drive her down to the station and charge her with resisting arrest and assaulting police.

The assault charge was in relation to her having kicked out at another officer whilst she was being choked by the first for breaking the mandatory mask rule. Mind you, her doctor had provided her with a certificate explaining that she couldn’t wear one for medical reasons.

The initial policing of enhanced pandemic laws in Victoria was so overbearing that a coalition of community legal centres established the COVID Policing website in April. It was monitoring the “inconsistent and sometimes arbitrary way” officers were enforcing extreme confinement laws.

But, the most disturbing instance of overpolicing in Victoria occurred in July when 500 officers were deployed to ensure 3,000 public housing tower residents remained in their flats in hard lockdown. Officers were stationed on every floor, while instructions were barked out over loudspeakers.

NSW: The Premier Police State

“The continuity of a legal regime requires the reiteration of the binding character of law, and to the extent that police or military powers assert the law,” writes American philosopher Judith Butler, “they not only recapitulate the founding gesture… but also preserve the law.”

Butler makes the comments in her 2020 book The Force of Non-Violence in reference to the work of early twentieth century German thinker Walter Benjamin. She adds that “the law thus depends on the police or the military to assert and preserve the law”.

The act of affirming and maintaining new laws has been played out by state police forces repeatedly across the country since the pandemic began, as officers went trigger happy issuing COVID-19 fines, which not only enforced the lockdown, but also a new prominence in the role of law enforcement.

This has now transpired into the application of chokeholds for the non-wearing of facemasks in public.

In NSW, premier Gladys Berejiklian took the escalation in policing one step further by placing NSW police commissioner Mick Fuller in charge of the state’s COVID response, which provided him with far-reaching control over not just his troops, but border force, defence force and health personnel.

“I don’t think anyone doubts that there will be an essential element for the police as we seek to enforce elements of a lockdown in response to a pandemic,” NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge recently remarked. “But that role should always be very much subservient to the role of NSW Health.”

And the gifting of this intensified control over the NSW citizenry to the leader of one of the largest police forces on the globe is quite concerning, especially when considering that prior to the onset of the pandemic, he was already making sniffer dogs and strip searches an everyday part of civilian life.

The ban on public assembly

The most obvious example of how these enhanced police powers are being reinforced to the point that they become the new norm is the NSW Police Force’s pursuit of the ban on public protest, which, while not having been pronounced in words, has definitely been imposed in actions.

Since the lifting of the complete lockdown in NSW, the police have been trying to prevent certain public demonstrations from taking place: whether that be via saturation policing or taking organisers to court, and it’s especially been the case with the recent surge in First Nations protest.

The Black Lives Matter-Stop Aboriginal Deaths in Custody demonstrations have been calling for an end to police brutality towards First Nations people, which, rather unsurprisingly, police have been trying to silence via court orders – one which succeeded, two which haven’t.

The other tactic that NSW police has relied heavily upon is saturation policing. At a planned 12 June BLM rally, officers built a blue barricade with their bodies in front of Sydney Town Hall, whilst at a prohibited July demonstration in the Domain officers outnumbered protesters to an absurd point.

It was at this last BLM demonstration that it came to light that pandemic laws are creeping into the post-lockdown setting, as an officer outlined to one demonstrator that gathering “for a common purpose” is currently outlawed.

Contained in the fourth iteration of the COVID-19 public health order, this is a ban on gatherings “for a common purpose” – read protests – greater than 20 people. This is regardless of any social distancing. And it morphed out of a lockdown prohibition on public gatherings of more than two.

So, it now remains to be seen how long the authorities can maintain this concealed outlawing of substantial public demonstrations, or whether it can be twisted into some more permanent application.