Free Them All: The Government Is Finally Releasing the Medevac Detainees

The former offshore asylum-seeking detainees that were brought to this country almost two years ago under the now revoked Medevac laws – and have since been locked up in hotels and immigration facilities – are slowly being released into the community.

As there has been no official announcements about what’s actually happening, the figures are fluctuating, but it seems that 46 Medevac detainees were released last week in Melbourne, following an initial seven released from their unwarranted detention in December.

Home affairs minister Peter Dutton said that the detainees were released because “it’s cheaper for people to be in the community” than it is to keep them in a hotel or a facility, which is a pretty ridiculous statement considering the billions that government has spent on offshore detention.

Refugee advocates who have long been campaigning for these men to be released are now celebrating. However, concerns are growing around those Medevac transferees left in detention, as they’ve been left hanging.

And as the minister quietly frees these refugees hoping nobody notices, the real tragedy is that Canberra enforced indefinite detention upon these people for close to a decade at great taxpayer expense, only to release them into the community they came here to join in the first place.

The toll on those remaining

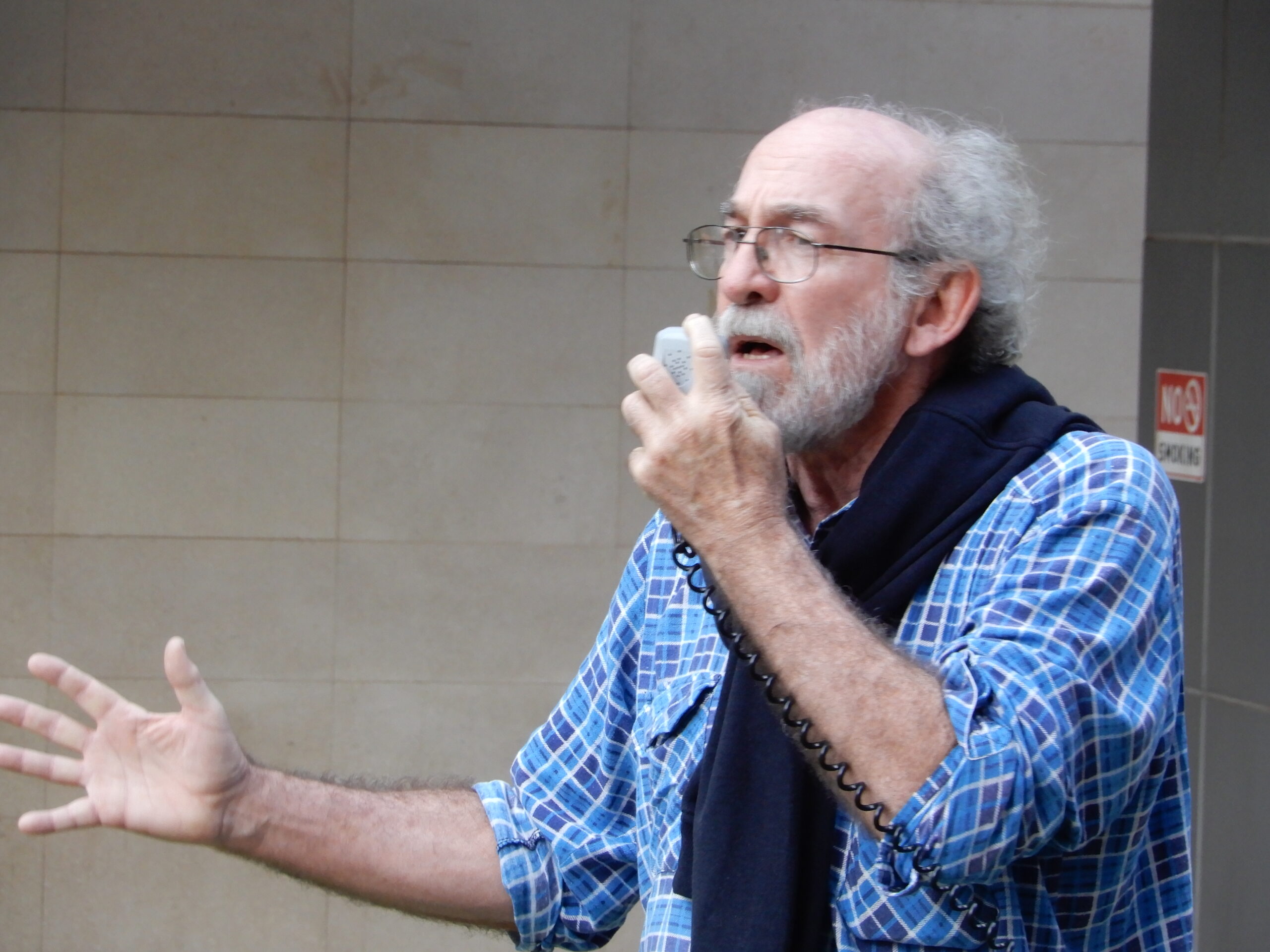

“It’s not before time,” said Refugee Action Coalition (RAC) spokesperson Ian Rintoul. “It’s two years that people have needlessly been kept in the hotels. And nothing has changed from when they were released to the day before, the month before to the last year.”

“So, it’s a very welcome development, but it has been such a long time coming and, of course, there are so many more people that still need to be released,” he continued.

The majority of the men set free last week were being detained in Melbourne’s Park Hotel, which is classed as an alternative place of detention (APOD).

However, the minister didn’t seem to consider how this would impact the 14 men left behind in the APOD, as a Bengali refugee attempted suicide a day later.

There continues to be 95 Medevac detainees held in Brisbane’s Kangaroo Point Central Hotel, where there’s been a sustained campaign for their release. And there are more refugees held in Sydney’s Villawood, as well as at the Melbourne and Brisbane transit facilities, known as MITA and BITA.

“This has created enormous anxiety amongst the people who’ve been left behind,” Rintoul told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “They have no idea whether they’re going to be in there for another week, another two weeks, or whether there’s any possibility of release.”

A legal loophole

“Ironically, the legal action that’s forcing the release is the request to be returned to Manus and Nauru,” Rintoul explained. “Although there has not been a legal finding as yet, because all the people involved have been released so far.”

Last July, Human Rights for All director principal Alison Battisson successfully argued in the Federal Court that her client should be released from long-term immigration detention, as the government couldn’t justify his prolonged and ongoing incarceration with there being no purpose behind it.

Referred to as AJL20, Battisson’s client is a 29-year-old Syrian man, who’s been a resident of Australia since he was a child. He’d been classed as an “unlawful noncitizen” under the Coalition’s character grounds deportation regime, and had since been detained for six years.

AJL20 requested to be sent back to Syria. And as government policy follows the international principle of non-refoulement, it couldn’t return the man to the war-torn country. Therefore, he had to be released as he wasn’t being held for imminent deportation.

Following on from this, a couple of lawyers filed multiple cases that were informed by the AJL20 ruling, which will never be determined as the government has released their clients without the courts being able to deliberate upon the argument they were set to present.

Released without support

“The legal action is primarily responsible,” Rintoul said. “But, of course, there’s been a massive protest campaign for the release of people from offshore detention and then, for the last couple of years, from the hotels since they’ve been here.”

And as the veteran refugee rights activist tells it, it’s now time for this movement – that consists of “refugee groups, church groups and community groups” – to step up as the Medevac detainees are being released into the community on six month bridging visas with almost no government support.

After holding these people in offshore detention for over six years, and then in hotels for close to two years, the Morrison government has now released them into the community with two weeks’ accommodation in a hotel in the Melbourne suburb of Reservoir and $150 to their name.

“You’ve got people who are really sick. They are mentally unwell. They have no opportunity for training or for English classes,” Rintoul stressed. “And they’re going to get no opportunity, because they’ve been placed into the community on bridging visas without that kind of support.”

So, despite being a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, the Australian government refuses to be these people’s saving grace, and it’s up to the huge support base in the community to accommodate and help them financially.

“You will never be settled here”

In July 2013, then PM Kevin Rudd unleashed the policy of offshore mandatory detention. And since then, this regime has been devastating in all aspects.

It’s involved the slow torture and deprivation of 3,127 people: 86.7 percent of whom have been recognised as legitimate refugees. And it has led to Australia being recognised on the international stage as a cruel, human rights-violating state.

Successive Australian governments have spent more than $12 billion on mercilessly detaining desperate people without justification.

Indeed, to hold the less than 300 people still detained on Manus and in PNG is going to cost over $1 billion this financial year.

And in the end, all this misery was for nothing, as the government has failed to achieve its stated aims.

“The fact is that we now have two to two and a half thousand people who were placed on Manus and Nauru now in the Australian community in one form or another,” Rintoul pointed out, adding that those now being released are “effectively being resettled in Australia”.

“Besides all the claims that Dutton makes,” the activist concluded, “it’s very clear that the policies have failed.”