Government Seeks to Protect Religious Freedom. Or Does it?

Throughout the same-sex marriage debate, there’s been a great deal of talk about religious freedoms.

To many, this seems highly ironic, as the point of the conversation was whether members of the community could have the same rights as others, which religion had forbidden in the first place.

But in a multicultural, secular society which nevertheless has many conservative Christians in powerful places such as government, issues to do with our nation’s most popular religion are bound to be afforded a sympathetic ear – and even trigger legislative change.

The same-sex marriage bill passed through the Senate on Wednesday. It’s the Dean Smith Bill, which was introduced just days before the postal survey was announced. An exorbitant amount of taxpayer money was then spent to find out what most of the community already knew.

The Senate made no amendments to the bill. The recommended changes were voted down, much to the credit of Labor. Right from the start, the bill already contained provisions to protect ministers of religion from acting contrary to their religious beliefs.

The public voted yes

After publicly declaring that the bill doesn’t “impose any restrictions on religious freedoms,” prime minister Turnbull has turned around and said he will support amendments that create greater protections, such as safeguarding charities, and allowing civil celebrants to refuse certain marriages.

This is despite the PM announcing that he’s setting up an expert panel to inquire into “whether Australian law adequately protects the human right to religious freedom.” And he was praised for this decision, as it allows for the passage of the marriage bill without this stumbling block.

Religious protections

Prior to Turnbull’s change of mind, he stated in a press release that the “proposals for legislative reform to protect freedom of religion… go beyond the immediate issue of marriage.” In his argument, it was self-evident that a review into religious freedoms should be undertaken as it’s a bigger issue.

The prime minister also suggested that any religious protection reforms “should be undertaken carefully,” which seemed to reiterate what his colleagues had been out there saying in the press the previous day.

Immigration minister Peter Dutton and defence personnel minister Dan Tehan had warned that any rush to legislate for religious freedom could leave the door open to the establishment of sharia law in this country.

In the current political climate, the mention of sharia law could lead one to think that it was just another veiled attack aimed at the wider Muslim population. But then again, no one would point the finger at minister Dutton for holding extreme prejudice.

Not so diverse

So, let’s take a look at the expert panel the prime minister’s putting together to inquire into whether religious freedoms are protected under Australian laws.

There’s Australian Human Rights Commission president Rosalind Croucher, Catholic priest and lawyer Frank Brennan, who was a yes voter, as well as former federal court judge and current Bond University chancellor Annabelle Bennett.

These experts seem more than qualified. However, it might be expected that in a multicultural society a review of religious freedoms would have some representation from some minority religions, who surely need protections most of all.

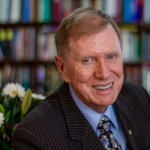

But if we turn to the head of the inquiry, the whole venture seems more suspect. Former Howard era attorney general and immigration minister Philip Ruddock is the man in charge. And he’s not known for being the most moderate voice in politics.

The Ruddock file

Mr Ruddock was attorney general at the time the Howard government amended the Marriage Act to add the definition of marriage as the “voluntarily entered into union of a man and a woman to exclusion of all others.” The change was to ensure that same-sex marriage couldn’t become a reality.

The former immigration minister was also the architect of the Pacific Solution: the policy of sending asylum seekers to offshore detention centres. He’s the man that set up the system that was the predecessor to the one that has led to the unfolding humanitarian crisis on Manus Island.

And Ruddock also called in the sham that was the Children Overboard affair. In 2001, he announced that asylum seekers on a boat that had been intercepted by the navy had thrown children into the ocean. Although, nothing of the sort had happened.

Once then-defence minister Peter Reith cottoned on that the story wasn’t true he kept it to himself, as a federal election was coming up. Reith eventually announced the reports weren’t true after the election, but by then the public’s perception of asylum seekers had been greatly tarnished.

Those anti-discrimination laws

The religious freedoms review is following the Human Rights Sub-Committee inquiry into the status of the human right to freedom of religion or belief, which the Australian reported on Thursday was reporting its findings.

It was expected that the inquiry would announce that there are little legal protections for freedom of religion in Australia, and these belief systems are further restricted by state anti-discrimination laws.

Liberal MP Kevin Andrews chaired the committee. In April, he wrote in the Australian Financial Review that the section of the Australian constitution that relates to religion, section 116, does not protect religious expression.

But the section does prevent the Commonwealth from making any law to establish a religion, or from prohibiting “the free exercise of any religion.”

Mr Andrews then points to article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which provides that “everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” He explains that this right has not been adopted into Australian law.

However, as contained in article 26 of the ICCPR, the right against discrimination has been.

Protections that are needed

So, the same-sex marriage debate has posed a threat to religious freedoms. But, it seems the real concern around these freedoms is the threat posed by anti-discrimination laws.

And we’re back to the same area of argument around section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act. Conservative forces want to amend that section so it’s no longer an offence to “offend” or “insult” someone on the basis of their “race, colour or national or ethnic origin.”

As George Brandis remarked back in 2014 the change is needed as people “have a right to be bigots.”

But, stepping back from that argument for a moment, we might ask why a country like Australia has found it necessary to legislate against discriminating against diversity, while it’s never been an imperative to legislate to ensure that majority religions are provided further protections.