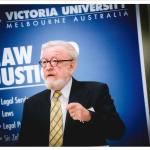

Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa’s Dr Julian Buchanan on Legalising All Illicit Drugs

Drug law reformists in the state of New South Wales are currently grappling with a government that has reneged on preelection promises regarding changes to the jurisdiction’s drug laws, with a slated NSW drug summit to deliberate upon drug decriminalisation, cannabis legalisation and pill testing.

Indeed, the days when the constituency was broadly in favour of the century-old system of drug prohibition are over, as it’s now readily understood that drug war outcomes are the opposite of those it seeks to achieve, with the Uniting Church NSW.ACT leading this call for change.

Meanwhile, across the ditch in New Zealand, pill testing or drug checking services have been operating legally and on a permanent basis since 2021, although Aotearoa’s cannabis legalisation referendum of 2020 resulted in a narrow majority of the nation voting against the change.

Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa, however, plans on dramatically changing the drug law reform agenda in our nation’s nearby neighbour, as it seeks to address the issue of illicit substances by simply legalising and regulating them all.

So, no longer will people who use drugs be outlaws.

Ending the drug war

Officially, launching on 7 May, Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa posits that as it’s now widely understood that the drug war has failed, and rather than take small steps to progressively achieve the end goal of legalised regulation, why not make it in one bound.

Whilst the system of drug decriminalisation has been successfully operating in Portugal, to the great benefit of the entire society since 2001, NZ’s Dr Julian Buchanan, a former UNDOC advisor, asserts that this system leaves unregulated black market psychoactive substances the only choice on offer.

A long-term drug law reform advocate, Buchanan further points out that the war on drugs has been a human rights travesty since inception, with governments infringing upon people’s bodily autonomy and in turn, imprisoning them over what they choose to ingest.

And the scope of what HRCA is calling for includes the abolition of its nation’s two major pieces of drug legislation, and for it to be replaced with one Act that would serve to govern the availability of quality controlled psychoactive substances that are today legal and illegal.

Support from on high

Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa is launching next Tuesday, when it will present the Luxon government with an open letter that calls upon it to rescind the nation’s failed drug laws, in line with recommendations from the New Zealand Law Commission Review in 2011.

The open letter includes a plethora of academics, nongovernment organisation workers and people who use drugs. Included on the list are representatives from Drug Injecting Services Canterbury (DISC) Trust, Students for Sensible Drug Policy, Law Enforcement Action Partnership and Unharm.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Dr Julian Buchanan from Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa about how the organisation considers that drugs would be available via a legal market, how NZ and Australia compare on drug law reform and how the coalition aims to progress its agenda.

Julian, on International Harm Reduction Day 2024, which is 7 May, Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa will be launching in New Zealand. And HRCA’s appearance is significant as it’s calling for the complete abolition of drug prohibition, and it has a lot of support behind it.

So, how did Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa come about?

About three years ago, Alex Hon Kuen Ho was taking cannabis for his autism, which he found to be effective.

But he became increasingly frustrated with the barriers and threats posed by drug prohibition that he was forced to stop self-medicating.

While his knowledge and experience of drug politics was limited, he had the tenacity and determination to tackle the issue.

Alex called together anybody who would listen. His disarming humility, openness to learning and persistence, combined with the fact that he had no allegiances or connections with any organisation, eventually resulted in growing support from a number of diverse people, including academics, NGO workers and people who use prohibited drugs and want to see drug reform.

After two years of discussions and ad hoc meetings, led by Alex, Wendy Allison, a pioneer who helped to establish drug checking in New Zealand, and myself, a core group emerged that eventually led to the creation of HRCA as an incorporated society chaired by Lachlan Akers.

People support HRCA because they see the need for an independent, free thinking, nonpartisan pressure group that would campaign for fair and just drug laws based upon human rights and harm reduction.

So, what sort of support are you talking about?

Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa launches on 7 May. And we already have over 50 individual members including: professors, doctors, people who work in the drug field and people who use prohibited drugs, along with support from six organisations, including New Zealand Needle Exchanges, the Drugs Health and Development Project, Auckland Drug Information Outreach, Know Your Stuff NZ, Students for Sensible Drug Policy and HIT UK.

At our launch on International Harm Reduction Day, we are presenting an open letter to the New Zealand government calling for the Misuse of Drug Act 1975 (NZ) and the Psychoactive Substances Act 2013 (NSW) to be rescinded.

We want the current legislation replaced with a new fit for purpose, evidence-based law that legally regulates the supply of all psychoactive drugs, including alcohol nicotine and caffeine.

Our open letter has over 125 signatures from a wide range of people including six professors and 29 doctors.

It is endorsed by 25 organisations and supported by experts from fourteen countries across North America, South America, South Africa, Europe and Australasia.

The vast majority of signatures are from folk in Aotearoa.

In New South Wales, the current drug law reform debate involves premier Chris Minns past year reneging on his party’s drug law reform agenda, once the Murdoch press pushed him on it.

So, this state continues to consider drug decriminalisation too radical a position, and it continues to refuse lifesaving pill testing.

At present, decriminalisation is the goal of harm reduction experts in NSW. However, Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa is calling for legalisation and regulation.

So, why does HRCA consider moving directly toward legalisation, as the solution to over a century of drug prohibition, rather than decriminalisation?

Governments across the world once thought abolishing slavery was too radical.

Governments thought it was too radical for woman to have equal rights, too radical to recognise the rights of Indigenous people and too radical to make homosexuality legal.

Thank goodness, campaigners didn’t lower their demands to appease government officials who thought them too radical.

HRCA fully supports decriminalisation. Decriminalisation is an easy first step towards the full legal regulation of all psychoactive substances, but decriminalisation cannot be the goal.

Decriminalisation is merely a transitory stepping stone.

The serious problem with decriminalisation is the supply of psychoactive drugs remains illegal and thus, stays underground in the hands of criminals, by definition, and gangsters.

When drugs are bought from underground sources the consumer has little or no idea of the content or purity of the drug, making the risk of overdose and death considerably higher.

This risk increases when their regular dealer is removed by the police, as consumers search for new suppliers.

When dealers are removed by law enforcement, community conflict, tension and violence increase due to turf wars between competing suppliers.

Any dispute between consumers or sellers can only be resolved by threats, guns, knives or baseball bats – there is no legal recourse.

Decriminalisation also fuels and feeds a massive lucrative criminal market and denies the country of taxes for much-needed public services.

In 2019, New Zealand adopted one model of decriminalisation giving police discretion not to arrest for drug possession if they consider a health approach to be more beneficial.

As a result, there has been a significant reduction in Pākehā, European descent, prosecutions for possession but no decrease in Māori prosecutions.

Decriminalisation can take on various forms but when enacted through the lens of prohibition it so often leads to ongoing harassment and punishment towards people of colour, Indigenous people, the poor and needy, who can still be arrested, stopped and searched due to legal exceptions given to police.

And why would you say HRCA is calling for the legalisation of all illicit substances?

In years to come, people will look back with incredulity at the arbitrary and brutal regime of drug prohibition that has had a devastating impact on individuals, families, communities and nations.

It should not be described as a ‘war on drugs’ because a highly selective range of psychoactive substances, which governments would rather we did not call drugs, are peddled, promoted and taxed.

The government has fiercely tried, and failed, to prevent people using unapproved psychoactive substances, many of which are significantly less harmful, than the psychoactive substances the government has approved.

This ‘war between drugs’ has failed dismally to reduce the supply or the demand for prohibited drugs, and has made the use of prohibited drugs considerably riskier and spawned additional harms.

The so-called global war on drugs was never based upon science or evidence, when it was announced by US president Richard Nixon in 1971. The policy was based upon political propaganda and vested interest.

The current legal framework for the management and control of psychoactive substances is clearly broken.

When campaigners in the past tried to tackle inhumane and ideologically driven laws, such as slavery or South African apartheid, they didn’t seek to tweak or reform slavery or South African apartheid – they sought abolition.

Nor should we tweak or reform a fundamentally flawed and corrupt system of drug law that is built upon the lies and propaganda from last century.

We need a new fresh paradigm to develop new drug laws fit for purpose, based upon science, evidence and experience – laws that respect human rights and promote harm reduction.

All drugs need to be legally regulated otherwise they simply remain in the hands of criminals and the dodgy underground market.

The greater the risk posed by a drug, the greater the need for that drug to be legalised to minimise harms and make it easier for people to access treatment without stigma or fear of arrest.

It is important to recognise adults currently have easy access to buy and use the most harmful and risky drug of all: alcohol.

Yet, despite the alcohol industry being poorly regulated and the drug having a near monopoly position as the drug of choice for almost every social occasion, society has not collapsed, and nor has the sky fallen down.

If we can live with and manage alcohol despite its privileged and promoted status as the ‘go to drug’, we can live with other less harmful drugs, especially if they are more responsibly regulated, under new legislation.

A vast range of harms we associate with illicit drugs are actually harms exacerbated or caused by prohibition: crime, addiction, overdose, violence and infectious diseases.

We know that prohibiting these substances is having little or no impact upon demand or supply, so we have to ask what is being achieved? The answer: vast cost and damage to society.

Prohibition thrives on drug exceptionalism, in which a few psychoactive drugs are legally approved and promoted, not because they are safer or more desirable, but because they are popular amongst those in power, and industries are able to financially exploit this privilege.

Extending this privilege to one or two more drugs is not the way forward, that would only perpetuate and reinforce the deeply flawed, damaging and corrupt system of prohibition.

Responsible legal regulation of the drug supply is the sensible and responsible way forward.

It’s not as if legalisation will introduce drugs to New Zealand. The drugs are already here. They are easily available and widely used.

So, we need to stop burying our heads in the sand and learn to live with people using psychoactive drugs, as people have throughout history.

We need to learn to manage drug use in a mature and well-informed manner.

The idea of legal cannabis doesn’t shock like it did a decade ago, as whole nations and half of the US now has legal recreational ganja.

But the idea of legalising drugs like heroin and meth continues to raise eyebrows.

How do you propose the legalisation and regulation of these substances would work?

The raising of eyebrows is largely a cultural construct. There was a time when people would have raised their eyebrows at seeing a woman judge, a woman surgeon and a woman airline pilot.

People would raise their eyebrows at seeing Indigenous people in government. People would raise their eyebrows at seeing same sex people holding hands.

Such ignorance, prejudice and misinformation cannot be allowed to get in the way of doing what is right.

The images you may have of people whose lives are in a total mess ‘because of drugs’ are for the most part images of desperate people with chronic unmet needs, such as physical or sexual abuse, serious mental illness, learning disabilities, damaged childhoods, homelessness or complex needs.

For this group with chronic unmet needs who feel they have no hope, drugs are a means of masking the unbearable reality of their everyday life.

For us to imagine their lives would be otherwise okay if it wasn’t for a particular drug is naive, over simplistic and fails to notice their real needs.

People can and do manage their lives while using drugs, even higher risk drugs such as alcohol, heroin and methamphetamine.

Indeed, there are lots of people who are prescribed opioids, such as methadone, and lots of people prescribed stimulants, such Adderall and Ritalin, which are almost identical to methamphetamine – not identical to street methamphetamine as that can be mixed with all sorts – and lots of people, who use these higher risk drugs function fine.

We need a new law to legally regulate the supply of psychoactive drugs. This would include a major review of the way we have regulated alcohol in respect of advertising, sponsorship, the display of consuming alcohol on most TV shows and movies, the sale of alcohol in supermarkets and airport duty free.

The supply of all psychoactive drugs needs to be responsibly and strictly regulated in terms of distribution, supply, promotion, advertising, labelling and selling.

Adults don’t need regulating, they need reliable evidence-based health promotion material, support and treatment services for the minority who develop issues.

Drugs which pose greater risk and may be more difficult to manage can be restricted to being legally available, via prescription, other less risky substances could be purchased over the counter at pharmacies, while the least risky drugs could be gradually introduced at pubs, bars, restaurants and cafes, which already serve as supervised drug consumption rooms for people to use alcohol, caffeine and in some instances, nicotine.

Legal regulation arrangements will need to be flexible, adaptable and responsive to cultural patterns of use, risk and unregulated supplies.

Regulation should ensure it is never more attractive, affordable or far easier to acquire drugs underground.

A key goal of legal regulation is to keep people away from illicit markets and the associated problems they spawn.

To reduce risk, practical, accessible and supportive harm reduction information and service provision should be more readily available to help people who use psychoactive drugs do so safely and in a much better-informed manner.

Treatment services should be based on evidence and aim at helping people to quit particular drugs or helping them to use in a more controlled manner.

Once drugs are legal and culturally accommodated, a more adult and sensible conversation about them can begin, which is away from the demonisation, hysteria and misinformation that dominates stories about prohibited drugs, which are narratives illustrated by nonsense about instantly addictive drugs, crack babies, flesh eating drugs and overdose from touching fentanyl.

Legalisation will open the door for medical research into the benefits of prohibited drugs to treat a vast array of conditions.

Bear in mind that these drugs are already available illegally without restrictions or regulations, and they’re widely used and can be acquired as quickly as you can order a pizza.

There is no age limit, no quality control, no labelling and no information, whatsoever.

Legalisation is not introducing drugs, it is removing the need for the consumer to engage in a criminal underworld, removing the uncertainty of not knowing what is being taken, removing the fear of being given a criminal record, the stigma from seeking help and it is providing people with safe spaces and support networks.

Legalisation removes a wide range of harms wrongly attributed to the drugs themselves.

Aotearoa-New Zealand is generally considered more progressive than Australia on most social issues.

This was recently evidenced when it rolled out pill testing nationwide. However, the nation did vote down a referendum on legal cannabis.

How is the general social climate for drug law reform in New Zealand at present? And how do you consider it compares with Australia?

Globally, drug prohibition has largely been managed to fly under the radar of social reform compared to laws that have been rescinded in respect to woman, homosexuality, Indigenous people, suicide, abortion, learning disabilities and ethnic minorities.

It is only recently that some people are beginning to acknowledge that imprisoning people for what they choose to ingest is a human rights abuse.

Like suicide and homosexuality, people should never be arrested, punished or imprisoned for what they choose to do with their body.

In extreme cases, it could be considered a health and social care matter but not a matter for the police. Everyone should have the right to bodily autonomy.

In respect of drug policy, I see little differences between Australia and New Zealand.

Sadly, the discourse surrounding drugs is dominated by institutionalised fear, ignorance, prejudice, propaganda and misinformation, which is embedded in our legislation.

The endless evidence-based discussions about drugs have too often been confined to inquiries, committees, working groups, reviews, academic conferences, journals and annual meetings at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in Vienna.

Drug policy has wrongly been thought to be too controversial for the public, so the public have been sidelined from proper debate and instead, left to be spoon-fed by propaganda, fear and hate by the media, politicians and those with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

Over the past decade or so, social media has enabled a much wider dissemination of evidence and points of view, not always for the best.

But if drug law reform is to occur, the public need to see and understand the lies they’ve been told about drugs, addiction and the damage caused by prohibition.

As Dr Sanjay Gupta, the USA Advisor to the White House, admitted:

“I mistakenly believed the Drug Enforcement Agency listed marijuana as a Schedule I substance [that is, no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse] because of sound scientific proof.

They didn’t have the science to support that claim. It doesn’t have a high potential for abuse, and there are very legitimate medical applications.

In fact, sometimes marijuana is the only thing that works.”

The century of drug prohibition continues. Although, the last 15 years have seen a dramatic shift globally, as the war on drugs is readily accepted as a failure, while the general edifice remains.

How do you foresee the drug issue playing out over the coming decades? Will this opening up continue?

We are struggling with institutionalised discrimination towards the use of certain psychoactive drugs that the state and the UN seek to outlaw.

The inertia of the past fifty years suggests we will not see change coming from the top-down, as they have too much to lose.

Change will need to be driven from the bottom up. Indeed, the global drug law changes that we have observed over the last 15 years have been largely due to greater public awareness of, and exposure to, the truth about drugs, which has only become possible via social media and the internet.

Government laws once protected male power and privilege to convince the population that the subordination of women was acceptable, laws once convinced the population that Indigenous people needed to be removed ‘to be helped’ and laws convinced the population that homosexuality should be outlawed.

These ideologically-based laws were eventually overturned because of activism within those communities to expose and challenge the harm and tyranny.

The challenge today is to help society understand our laws on psychoactive drugs are similarly a devastating form of institutionalised discrimination based on prejudice, misinformation, vested interest and ideology – not science or evidence.

The tide is finally turning, although ever so slowly at the top.

At its 67th annual meeting in Vienna this year, the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs finally recognised that harm reduction is an important part of an effective public health approach to drugs.

Globally more and more people, doctors, academics, researchers, elected officials and journalists are also realising that our drug control policies are at least as harmful as the impact of drugs themselves.

Governments across the world are having to rethink prohibitionist drug laws. A range of alternative models of legalisation, decriminalisation and regulation are emerging.

However, unless these reforms address the misplaced fears, moral dogma and fallacious evidence base embedded within the current system, such reforms are likely to flounder – some may result in Prohibition 2.0.

Rather than tweak these bad laws built upon an unsound foundation, HRCA seeks to rescind these laws and develop a new Psychoactive Drugs Act that would responsibly legally regulate all drugs.

The Act would be fit for purpose, based upon sound evidence, experience and science.

New Zealand has the opportunity to be on the right side of social reform once again: to be a pioneer and end the debacle of drug prohibition.

HRCA will engage in a sustained effort for an open, well-informed and mature dialogue with the public to expose the truth about our draconian drug policy and deliver world leading drug policy reform.

Julian, Harm Reduction Coalition Aotearoa is in its infancy. However, those behind it have long been working in the drug law reform and harm reduction space.

What sort of strategy does HRCA have in mind for progressing its position? What impact does it plan to make?

Our six objectives are:

One, establish cross party and nonpartisan support to end drug prohibition by rescinding the failed Psychoactive Substance Act 2013 and the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975, as recommended in the New Zealand Law Commission Review in 2011.

The second objective is to ensure all adult possession, cultivation and production of all drugs is legal for personal use.

Third is to dismantle all policies that reinforce drug prohibition. And the fourth focuses on securing the annulment of all criminal records and convictions related to adult personal possession, cultivation and production of drugs.

Fifthly, we want to ensure drug policies are rooted in science and evidence, in order to uphold the principles of harm reduction and human rights.

And lastly, we want to promote a new Psychoactive Drugs Act managed by Health, which would regulate all aspects of the supply of psychoactive substances.

This would include those psychoactive substances that are currently legal and those psychoactive substances that are currently prohibited.

We will remain fiercely independent, inclusive, nonpartisan and dedicated to promoting rational evidence-based approaches to drug policy that honour the Te Tiriti: the Treaty of Waitangi.

The breadth and depth of expertise across our membership will provide insight and wisdom to speak out with authority on issues but always in a carefully considered and well-informed manner.

Whenever opportunities arise, we will take the debate to the public to build a much-needed bottom-up demand for drug laws that do no harm.

HRCA will do all it can to disseminate the evidence and truth about drugs, addiction and drug prohibition harm to the wider public, as well as bring pressure to bear upon NGOs, government agencies and elected officials.

HRCA will be a pressure group that’s here for the long haul. We are still in our infancy, and everything achieved so far has been carried out by volunteers in their spare time.

If we are able to secure donations or funds to appoint an administrator and/or coordinator that would be a considerable help taking HRCA forward.

Anyone can donate to HRCA, or become a friend, which is free, or join and become a member, which involves a fee of NZ$10 for the waged and NZ$2 for the unwaged.