High Court Rules Against Indefinite Detention, So the Majors Pass Laws to Reinstate It

Successive Australian governments have been undermining the rule of law when it comes to the practice of indefinitely detaining unlawful noncitizens that they won’t settle here and can’t return to their country origin due to international obligations set out in the 1951 Refugee Convention.

The Westminster democratic system that operates in Australia holds habeas corpus as one of its key principles, which requires that there must be a purpose for incarcerating an individual.

The full bench of the High Court ruled on 8 November that unlawful noncitizens can’t be detained in immigration detention indefinitely when there is no real prospect of them being deported to their country of origin in the near future. This was found to be the case with a detainee known as NZYQ.

This ruling brought an end to the indefinite detention regime that first took effect under the Keating government in 1994, it overturned the indefinite detention precedent set in 2004’s Al-Kateb, and the unanimous determination resulted in the release of 140-odd noncitizens into the community.

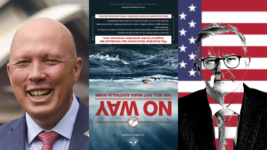

But the court didn’t release its findings on the 8th. And Liberal opposition leader Peter Dutton – the former minister who long ruled over immigration with an iron fist in tandem with the now defunct home affairs secretary Mike Pezzullo – took the opportunity to stir up a moral panic in the interim.

And what’s since transpired is that both major parties have progressed laws that ensure certain noncitizens can be reincarcerated without committing a new crime, and although such orders have a time limit, they can be reapplied repeatedly, ensuring that indefinite detention is alive and well.

Preventative detention

Initial kneejerk laws were passed on 16 November following the court decision. These were in the Migration Amendment (Bridging Visa Conditions) Bill 2023, which has established a strict parole-like regime for the released noncitizens, and it created new offences for noncompliance with it.

Then, one day prior to the court having publicly released its NZYQ full findings, Albanese introduced the Migration and Other Legislation Amendment (Bridging Visas, Serious Offenders and Other Measures) Bill 2023, which has since sailed through both houses, passing on 5 December.

This second piece of legislation creates a bridging visa framework for those affected by the NZYQ ruling, and it specifically “targets those with a serious history of offending in relation to the most vulnerable people in our society, including children”, the bill’s explanatory memorandum outlines.

This legislation also creates new offences, “with mandatory minimum sentences”, that criminalise those who partake in work that involves minors or vulnerable persons or go within 200 metres of schools, childcare or daycare centres or those violent or sexual offenders who contact their victims.

Community safety orders have also been created with the passing of these laws, which set up a regime of preventative detention for “serious offenders”, who comprise those released noncitizens that have been convicted of a serious violent or sexual crime in the past and cannot be deported.

Under this regime, the immigration minister may apply to a state Supreme Court to have a community safety order imposed upon a noncitizen, whom they consider to be a threat to the community.

If the court rules the order should be applied, the noncitizen can then be held in a prison for up to 3 years. Yet at the end of a community safety order period, the court can then decide to make ongoing successive orders, in a manner that begins to appear like indefinite detention, via the courts.

This regime, therefore, establishes a system whereby those who have served their time in prison for a serious crime can then be locked up once again, which is a form of double punishment. And this preventative detention only applies to foreigners, with local serious offenders not falling foul of it.

Getting around the ruling

The High Court ruling against indefinite detention was welcomed by legal experts and rights groups, as it had long been understood to fall outside the rule of law. But the extralegal nature of this practice did not prevent the Coalition from condemning Labor for not re-detaining all the released.

On questioning the attorney general Mark Dreyfus about the new laws on Wednesday, the ABC’s Laura Tingle described them as “getting around” the High Court’s determination that the executive cannot indefinitely detain noncitizens if they can’t be promptly deported.

“It is not a matter of getting around what the High Court has said,” the AG told the journalist. And he added that the High Court found that ministers can’t indefinitely detain noncitizens, but the full bench did state that a preventative detention regime could be used to continue their incarceration.

“So, that deals with the separation of powers by getting a judge to do it,” Tingle said, after Dreyfus set out how community safety orders work.

And the ABC journalist further questioned why these laws would standup to a legal challenge, and the AG confirmed that such preventative sentences are considered to be a form of punishment imposed by a judicial officer with the aim of keeping the community safe, which is all above board.

No solution at all

Greens Senator David Shoebridge criticised the initial post-release supervision regime that the Albanese government enacted to deal with these asylum seekers and stateless people who have been released from indefinite detention, especially as some have no criminal record whatsoever.

“It is astounding the way Labor has delivered government and political direction to Mr Peter Dutton and his mates over there,” Shoebridge said in the chamber this week.

“It is just an astounding national surrender, not only to surrender the direction of government to the Coalition, led by Mr Peter Dutton, but to attach onto this noxious legislation two of the most appalling provisions that offend pretty much every legal principle in the book.”

Shoebridge called out the system of future crime or preventative detention, which is the locking up of an individual on the off chance they may perpetrate an offence down the track, while mandatory sentencing also drew his ire, as Australian law prioritises other sentencing options besides prison.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to the Campaign for a Royal Commission into Immigration Detention spokesperson Julie Macken, who explained that the practice of mandatory detention, and at times never setting those who arrive by boat free, must be the subject of an official investigation.

“Australians don’t trust anyone very much at all anymore, according to all the trust indexes. In fact, we have never been so distrusting and our social cohesion has never been more fragile,” the long-term refugee advocate said. “But we do still trust Royal Commissions.”

“Without a Royal Commission this treatment is not going to change,” Macken added, which is a proposition that has been clearly evidenced since the High Court handed down its ruling in early November.

“We have seen 25 years that tell us it can’t change.”