In National Security State Australia, Press Freedom Is Just a Nice Idea

Hong Kong police raided the office of pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily on 17 June and arrested its five chief directors on national security grounds, while local authorities froze its assets, effectively shutting it down.

Beijing has been increasing its grip on the semi-autonomous city over recent years. The actions taken against Apple Daily were enabled by the Hong Kong National Security Law, which was imposed upon the region a year prior at the behest of the Chinese Communist Party.

China has never been known for its press freedom on the international stage. However, since the AFP conducted two raids on prominent journalists in mid-2019, neither is Australia.

Somewhat similar to the situation in HK, successive Australian governments have passed 90-odd pieces of national security-counterterrorism legislation, with bipartisan approval, since the September 11 attacks took place in New York in 2001.

And not only do these measures permit crackdowns on journalism, but it’s also leading to the political prosecutions of a number of whistleblowers for having exposed the crimes of government that an otherwise more transparent system might have prevented.

A national security law bonanza

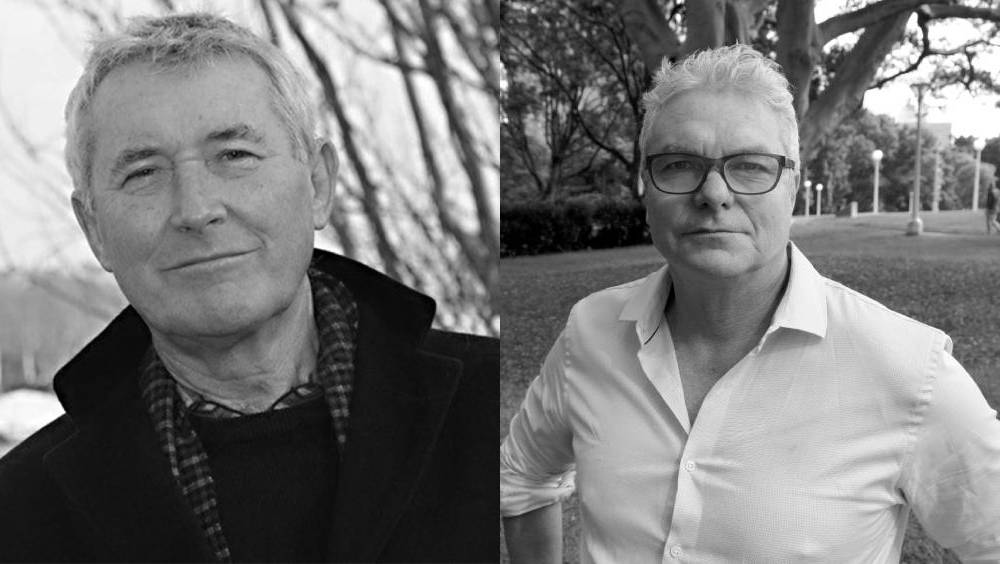

“There’s only one way to describe it and that’s very poor,” said Monash University Associate Professor of Journalism Johan Lidberg in reference to Australian press freedom. “This has been building up ever since September 11. We had issues before then, but that’s when it really took off.”

“You only need to go to the Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index and Australia dropped five places between 2019 and 2020,” the academic told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “We are placed 25th now.”

A major reason behind local press freedoms being in tatters, Lidberg posits, is the huge body of laws that have been passed since 9/11. He adds that while most nations tightened security following the terrorist attacks, Australia has outdone others in the number of laws it’s enacted in response.

And while defence minister Peter Dutton has indicated that Islamic terrorism is no longer the chief threat for our nation, prime minister Scott Morrison has suggested that further such laws awaiting the approval of parliament need to be passed in order to bolster our security agencies even further.

“Myself and other colleagues warned for years that it was inevitable that something like the 2019 AFP raids would happen,” Lidberg made clear. “There is no way if you give so much power to national agencies, it won’t be used.”

Criminalising journalism

The AFP raided the Canberra home of News Corp journalist Annika Smethurst on 4 June 2019, over having reported on leaked emails revealing Home Affairs and Defence discussing a proposal to turn international spying agency the ASD on domestic targets: a plan initially denied but since admitted.

On the following day, AFP agents raided the Sydney offices of the ABC, where they targeted journalists involved in The Afghan Files report, which uncovered war crimes committed by SAS troops in Afghanistan, via classified documents supplied by former military lawyer David McBride.

Following the raid, ABC executive editor John Lyons tweeted that he was “staggered” by the power of the warrant used by the AFP, which permitted it to “add, copy, delete or alter” files on ABC computers. This warrant was created by new national security laws passed under 2018’s TOLA Act.

Lidberg pointed to the 2015 data retention laws as an example of measures spruiked to deal with counterterrorism and cybersecurity being turned on journalists. These laws allow security agencies access to citizens’ metadata, which must be stored for the period of two years.

This access is warrantless, except in terms of perusing journalists’ metadata, where a warrant must be obtained, as a measure to protect confidential sources. And it came to light after the AFP raids that over 2017-18, the national police had accessed the metadata of journalists 58 times.

However, as Lidberg pointed out, in 2014, even before the metadata regime was established, the AFP accessed the data of Guardian journalist Paul Farrell on a number of occasions in an attempt to uncover his sources, without obtaining a warrant.

Political prosecutions

The persecution of whistleblowers has certainly picked up under the Morrison government. Witness K was just given a suspended sentence for exposing the 2004 Timor-Leste bugging scandal, while barrister Bernard Collaery has vowed to fight his charge over his part in the revelations.

There is a large body of whistleblower protection laws at the state and federal levels that apply to both the public and private sectors. Laws enacted to protect federal public service sector employees are contained in the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 (Cth).

“The problem is these provisions sit within government agencies, so they’re not independent enough and don’t offer the proper protection that a whistleblower needs,” Lidberg explained. “Most commonly, they go through the functions within departments and find it doesn’t work.”

After serving two tours as an official ADF lawyer in Afghanistan, David McBride attempted to raise his concerns about how special forces were operating in the Central Asian nation, but after exhausting all internal avenues nothing was achieved, so he went to the press.

“That’s why they still take the huge risk of going to the media and contacting journalists, because they’re so fed up with seeing the issues not being addressed,” Lidberg added.

The journalism academic further pointed out that Australia’s freedom of information system is lacking compared to those of other liberal democracies, which therefore necessitates a reliance on whistleblowers to expose such information, rather than relying on journalists sourcing it themselves.

Rolling back the incursions

In the wake of the AFP press raids, a Senate inquiry into press freedoms was established. Released in May, its report made 17 recommendations, which include agencies having to establish a genuine harm has been caused by leaked information prior to any criminal investigation being carried out.

Lidberg concedes that all governments need to operate under some secrecy, however the extent of the provisions enacted over the last two decades have not only impacted the capacity of journalists to do their jobs unimpeded, but they’ve also impinged upon the civil liberties of all.

“I’m not saying we shouldn’t have some level of secrecy,” he continued, “but we also need to make sure that we limit the reach of what’s classified as national security.”

In his joint press freedom inquiry submission with Dr Denis Muller, Lidberg recommends that an annual review of our national security and anti-terror laws should be undertaken, and those found to be unnecessary should be rolled back via amendments.

“Another aspect to this is the chilling of the media robs the public of an independent agent to hold the government to account as to how they use their power,” said Lidberg, adding that currently it’s almost impossible to meaningfully report on national security due to “the enormous web of laws”.

“There is a strong sentiment among journalists in Australia that it’s just too hard,” he concluded. “So, we have gone from a reasonable number of journalists having national security as their theme to hardly anyone.”