Indentured Labour in the British Empire: Slavery Reworked

In 1807, British parliament passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, which banned the practice of transporting enslaved African peoples to the Americas to be sold there. This brought to an end to Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, which began in 1562.

It’s estimated that British ships transported 3.4 million slaves across the Atlantic Ocean. Initially, British slave traders supplied Portuguese and Spanish colonies in the Americas. But later, with British colonial expansion, slave traders supplied British colonies in the Americas and the Caribbean.

The use of slave labour was abolished throughout the British Empire when the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833. At that time, there were 46,000 British slave owners, and the majority of their slaves were working on sugar plantations in British colonies in the Caribbean.

Under the provisions of the Act, the Slave Compensation Commission was established to oversee the distribution of £20 million in compensation to the slave owners for the loss of their “property.”

The liberated slaves were also required to provide 45 hours of unpaid labour a week to their former masters for the period of four years after the practice of slavery had been outlawed.

The abolition of slavery brought about a shortage of labour across the Empire. So, the British turned its eye towards another form of low cost labour: the indentured worker.

Bonded labour

On November 2 1834, three dozen Indian labourers arrived in the British colony of Mauritius. The workers were bound by five year contracts. They were paid 5 rupees a month, and their food and clothing were supplied by their employer: Hunter, Arbuthnot and Company.

The indentured workers set off from Kolkata about a month and a half after the Slavery Abolition Act came into effect. And it was six months’ pay in advance that enticed these labourers across the Indian Ocean to work on sugar plantations in a foreign land.

They were first of 2 million Indian indentured labourers that were sent to work in 19 British colonies, including Fiji, Ceylon, Trinidad, Guyana, Uganda, Kenya and Natal. And to a lesser extent, indentured labourers were also recruited from China, Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

Indentured labourers worked mainly on sugar plantations. But they also toiled in the tea and cotton industries. While some were employed in rail construction in southeast Africa.

Akin to slavery

Indentured workers were made to enter into five year contracts, which the majority were unable to read. Often the labourers made the journey by choice, as they were fleeing poverty and famine. Although, others were coerced or deceived.

Conditions on the ships were like those slave ships. Over the period 1856-57, 17 percent of Indian workers travelling to the Caribbean died at sea. While in 1870, the mortality rate for indentured labourers working in Jamaica was 12 percent, which was similar to the rate found in Mauritius.

Working conditions on the sugar plantations were harsh. The labourers were made to work long hours, corporal punishment was meted out and their pay was a fraction of what a British labourer could expect to receive at the time.

The nationalist campaign

In November 1860, the first Indian indentured labourers arrived in the British colony of Natal, which is now a part of modern day South Africa. These were the first of 150,000 workers sent over the next fifty years to work on the sugarcane plantations in and around Durban.

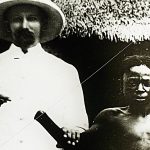

In 1893, Mahatma Gandhi arrived in the colony to work as a lawyer. He began campaigning for the rights of wealthy Indian traders the following year. But, it wasn’t until twenty years later that the future Indian independence leader turned his attention to the indentured system.

Gandhi led a passive resistance campaign in 1913, against a tax that had been imposed on former indentured labourers. The levy was eventually revoked. And at the same time, back in India, an anti-indentured emigration league began to gain the support of nationalists across the country.

This led to a resolution to abolish the indentured system being passed in the Indian Legislative Council in March 1916. The British government agreed to the motion, and formally banned the system in 1917. However, the migration of indentured labourers continued on into the 1930s.

The legacy today

Currently, the Indian community in Mauritius make up two thirds of the island’s population, where they dominate the public sector. Whereas, in Trinidad, the Indian community are excluded from political life and the public sector, which is run by Trinidadians of African descent.

While in Fiji, the descendants of the Indian indentured labourers have to a large extent been excluded from land ownership, or playing any part in the nation’s political life. Although, their situation has bettered since 2013, when they were given equal status in the constitution.

Blackbirding in the Antipodes

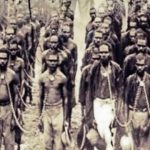

Australia has its own forgotten history of indentured labour. In August 1863, a ship carrying 67 men from Vanuatu entered Moreton Bay in Queensland. These were the first of an estimated 62,500 South Sea Islanders brought to this country to work under contract on the sugar plantations.

Some came by choice. But many were kidnapped, coerced and deceived in a practice that is referred to as blackbirding. These people faced slave-like conditions in the sugar plantations, much like the Indian workers did in the British colonies.

They were segregated from the rest of society and forbidden to speak their own language. The harrowing conditions, malnutrition and European diseases took their toll. An estimated 15,000 died within their first year of arrival. And this practice continued on for 40 years.

After federation, the government passed the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901, which was an order to deport the South Sea Islanders. Not all, but the majority were sent away, and this was funded with the labourers’ own wages, which had been misappropriated by the Queensland government.

Modern day slavery

In 2012, the International Labour Organisation estimated that there were 21 million people working in forced labour conditions globally. This is three out of every one thousand people, who are trapped in jobs that they were either coerced or deceived into.

The Asia-Pacific region accounted for the largest number of forced labourers at an estimated 11.7 million. In Africa there was 3.7 million victims, while Latin America had 1.8 million.

And last November, reports began emerging about West African immigrants being sold in slave markets in Libya. This followed on documented Libyan incidents being released by the International Organisation of Migration that revealed while slavery might be abolished, it still continues.