Is Accountability Finally Coming for Aboriginal Deaths in Custody?

NSW state coroner Teresa O’Sullivan made a landmark decision last week, when she cut short the inquest into the death of 43-year-old Wiradjuri man Dwayne Johnstone and referred the matter to the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) to consider whether charges should be laid.

Handcuffed and shackled, Johnstone was in the custody of two Corrective Services NSW officers outside Lismore Base Hospital on 15 May last year, when he made a break for it. One officer then fired three shots at the 43-year-old, with the third fatally penetrating his back.

On 29 October, O’Sullivan told the court that she’d reviewed a five volume brief of evidence tendered on the first day of the inquest, which led her to conclude that a threshold had been reached which warranted DPP referral.

This decision is significant because First Nations custody deaths are rarely, if ever, sent to the prosecutions office for consideration. And if charges are laid and a prison officer is found guilty, it would be unprecedented.

A system built upon

The Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody tabled its final report in April 1991. It made 339 recommendations, with only a few ever having been implemented.

Since that time, there have been at least 441 further First Nations deaths in the custody of police and corrections, which is a rate of more than one death per month over the last 29 years.

The circumstances around Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander custody deaths, for the most part, amount to excessive force, violence and neglect.

However, with officials almost never being held responsible for their actions, adequate reforms and changes in behaviour aren’t taking place.

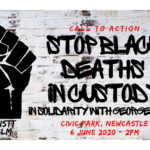

The recent rise in the Black Lives Matter movement has renewed focus upon the systemic racism within Australian policing and corrections systems, which were founded upon the prejudicial treatment and brutalisation of First Nations people – with accountability never an official concern.

Held to account

Another ground-breaking decision was made last week in the case of the death in custody of Warlpiri man Kumanjayi Walker, as the Alice Springs Local Court ruled that NT police officer Zachary Rolfe will stand trial for murder.

This marks the first time a police officer from the territory will be tried over an Aboriginal custody death since the handing down of the Royal Commission report.

Walker was shot three times by Rolfe on 9 November last year. The constable and another police officer entered the 19-year-old’s Yuendumu home in what’s been described as a late-night military-style raid, with the aim of arresting him over breach of bail.

The incident has led the Yuendumu community to call for an end to police violence, harassment and armed patrolling.

The Warlpiri elders want the right to patrol their own community re-established, as at present, the police are treating the Indigenous people like enemies on their own land.

A charge of murder in the west

The history making NT murder trial announcement follows on another significant sign that justice might finally be brought to bear in cases of First Nations deaths in custody, as a Western Australian police officer is also to be tried for murder.

On 17 September last year, a Yamatji woman known as JC was shot by a police officer out the front of her family home in Geraldton. The 29-year-old was holding a knife and surrounded by police officers at the time.

JC suffered from mental health issues. And her family had called the police to ask for their assistance in transferring her to a hospital as she was having difficulty at home following release from prison.

The WA Supreme Court confirmed in September that the murder trial will take place in Perth late next year.

It will be the first time a WA police officer has stood trial over an Aboriginal custody death, since the 1983 killing of John Pat saw five officers stand trial for manslaughter and acquitted by an all-white jury.

Justice dashed

But, while progress seems forthcoming in these cases, a decision made by the Victorian state coroner last April to refer the death in custody of Tanya Day to that state’s DPP for possible charges was ultimately denied, when Victoria police announced no charges would be laid in August.

Aunty Tanya died in hospital in December 2017, after sustaining head injuries in a police lockup and left lying on the floor of her cell for three hours. Coroner Caitlan English found that the behaviour of two police officers on duty at the time could amount to criminal negligence.

A 55-year-old Yorta Yorta woman, Ms Day was taken into custody for being drunk in public. And despite the Andrews government committing to revoke this highly prejudicially-applied law in August last year, the offence still appears on the books.

Deaths in NSW

The inquest into the death in custody of 36-year-old Gamilaraay man Nathan Reynolds was adjourned last week.

The NSW Coroners Court heard a raft of evidence pointing to negligent treatment of the inmate who suffered a severe asthma attack, yet received belated assistance.

The final day of the coronial inquiry is set to take place this December.

And last week also marked the commencement of the NSW parliamentary inquiry into the overincarceration of First Nations people, as well as why justice is not being served when it comes to Aboriginal deaths in custody in this state.

Initiated by Greens MLC David Shoebridge, the inquiry follows widespread grassroots outcry over ongoing deaths in custody this year, which had as its central focus the death of David Dungay Junior, who was held down in the prone position by five prison guards until he died in December 2015.

The Dungay family consulted Sydney criminal barrister Phillip Boulten SC in July, who advised them that there’s potential for charges to be laid in regard to David’s death in custody.

Yet, so far, the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions has not acted upon this advice.