Jesus the Agitator and the Perrottet Anti-Protest Regime: An Interview With Historian Diane Fieldes

The right to protest is under attack in the state of NSW, elsewhere around the country and, indeed, across the western world. And the reason for this is well understood: disruptive protests are drawing attention to the escalating climate crisis and the authorities want this message shut down.

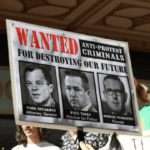

The Roads and Crimes Legislation Amendment Bill 2022 (NSW) was rammed through both houses of parliament, with bipartisan approval, over a 48 hour period early last year. And the legislation, effectively, stamped out a spike in unapproved climate protests that were sweeping Sydney.

Coupled with some tweaks to the regulations that were made earlier by NSW roads minister Natalie Ward, the anti-protest legislation established a new regime that sees the unauthorised blocking of roads, bridges, tunnels and major facilities carrying two years prison time.

However, much of the NSW constituency weren’t aware of to the full implications of these measures until climate defender Violet Coco was sentenced to 15 months gaol on 2 December, over having briefly blocked one lane of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in an act of nonviolent direct climate action.

Jesus the protester

In her 2013 Red Flag article The Contradictions of Christianity, Sydney historian and activist Diane Fieldes gives an account of Jesus of Nazareth, highlighting that in the Jewish tradition, he is no son of a deity, but rather he’s an all too human messiah or radical liberator.

And the author further points out that early Christians living under the Rome Empire were mainly from the lower classes and were agitating against its oppressive rule, following the lead of Jesus.

Perhaps the most prominent protest action taken by Jesus was when he entered the Temple in Jerusalem, which had a courtyard overrun by moneylenders, whom he drove from the complex, signalling a disdain for such practices.

As Fieldes explains, it wasn’t until the fourth century when the Roman Empire adopted the belief system of Christianity as its official religion, that what had once been a doctrine of dissent, became an “ideology of empire, war and power”.

Christians in their midst

Over recent years, there has been a rise in evangelic Christians, and especially Pentecostals, joining the Liberal Party, as well as within its ranks in parliament. Former PM Scott Morrison and his religious freedoms crusade was a prime example of this.

Whilst NSW premier Dominic Perrottet isn’t a follower of radical Protestantism, he is a devout adherent of the conservative Catholic sect of Opus Dei.

So, it seems somewhat pertinent to ask how Jesus and the early radical Christians might have fared under his government’s new anti-protest regime.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Socialist Alternative member Diane Fieldes about the radical roots of Christianity, whether early adherents would have fallen foul of Perrottet’s laws, and how she considers the focus on a politician’s religion should be secondary to that on their political beliefs.

In The Contradictions of Christianity, you give an account of the Christian faith originating “as a religion of the persecuted and oppressed”, which was appropriated by Rome for political purposes and while it maintained its central egalitarian message, it became “an ideology of empire”.

You further point out, that in the Jewish tradition Jesus is not a deity, but rather a messiah, or a radical leader, and he was agitating for the rights of the urban poor living under Rome.

Diane, can you elaborate on who this Jesus figure is in the historical reading?

You are quite right about Christianity’s origins as a religion of the persecuted and oppressed, but little of that survived. For most of its history, the church has sided with the rich and powerful.

Indeed, it has been a major institution of ruling classes from the feudal nobility to the modern capitalist class.

But it is true that in its origins, and at many points subsequently, Christian ideas have also given expression to rebellion.

The way that the Marxist writer Paul Siegel puts it in his book The Meek and the Militant is wonderfully clear: The yearnings of the impoverished Jewish masses under the decaying Roman Empire produced Jesus Christ.”

The Roman Empire, based on slavery, impoverished the vast mass of those who lived under it. The early Christians were mainly members of the non-slave lower classes.

They wanted liberation from that misery, and they weren’t interested in waiting for the afterlife to get it. They were not the first or only ones to rebel.

There were many popular revolts against Roman occupation and class oppression, all of them led by messiahs – saviours or liberators –armed with aspirations expressed in religious terms.

These historical figures provided the basis for Jesus. There is no historical evidence that the individual Jesus Christ actually existed.

Would you say that the figure of Jesus as an agitator, or those figures his story was based upon, took part in what might today be called nonviolent direct actions?

The figures on whom Jesus is based, and their followers, were routinely attacked, dispersed, imprisoned, enslaved or killed by the Roman forces.

The Jesus of the early Christians is the messiah of the Jewish tradition, rather than the deity that he later becomes. He’s an activist.

Despite later editing designed to remove these elements of early Christianity, the New Testament still contains bits of its early radicalism:

“He has brought down mighty kings from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly. He has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away with empty hands.” (Luke 1:52-53)

They did not confine themselves to nonviolence, having more of a “by any means necessary” approach.

Jesus appears as a radical leader, throwing the moneylenders out of the temple:

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the world. No, I did not come to bring peace, but a sword.” (Matthew 10:34)

“Whoever does not have a sword must sell his coat and buy one.” (Luke 22:36)

The actions of Jesus and the early Christians were disruptive to the business as usual of the Roman Empire.

The NSW government has recently rolled out new anti-protest laws designed to stamp out peaceful but disruptive climate defence actions.

If they were operating today, would the NSW laws impinge upon the agitating of Jesus or his early followers?

Today, the early Christians would no doubt already be in jail, given that Violet Coco got a 15 month sentence for blocking a single lane on the Harbour Bridge for 25 minutes.

They were animated not just by the desire to throw the moneylenders and tax collectors out, but by a desire to bring down the Roman Empire.

The NSW Liberal Nationals government has conservative Christians in its ranks, and this includes premier Dominic Perrottet.

The NSW anti-protest regime targets grassroots climate defenders trying to save the entire planet. So, in considering it alongside the activities of early Christians, how do you consider the actions of the Coalition at present?

A dozen more climate activists in NSW still face charges for “serious disruption” of pedestrians and vehicles under the Roads and Crimes Legislation Amendment Act 2022.

This means that protesting on roads, rail lines, bridges, or in tunnels and worksites, can land activists with fines of up to $22,000 and prison sentences of up to two years.

This is the most serious attack on the right to protest in Australia in decades.

And it is perfectly in accord with NSW Liberal premier Dominic Perrottet’s Christian beliefs for him to describe the jailing of Violet Coco as “pleasing to see”, saying that protest should be allowed only if it “doesn’t inconvenience people”.

The Catholic Church long ago stopped speaking of bringing down kings or creating justice on Earth.

The Christian message from around 312 CE, when the Roman emperor Constantine the Great became a Christian and gave the church official sanction, is that everyone must obey state authorities, because no authority exists without God’s permission, and the existing authorities have been put there by God. (Romans 13:1)

As class society changed from feudalism to capitalism, Christianity provided religious justification for the economic and social needs of the capitalist class.

So, what comes first is class interests, not the religious ideological justification for them. Religion of any kind is not an indicator of whether you are a better or worse person politically.

In terms of conservative Christians in parliament, over recent years, there seems to be an increasing number of evangelical and fundamentalist Christians in high Coalition ranks.

Indeed, in South Australia, Pentecostals were caught out in an attempt to infiltrate the SA Liberals with the aim of shifting its policies to line up with the church’s agenda.

How do you consider the rise of conservative Christians in the Australian political system?

As mentioned before, the religious beliefs of those who run capitalism are secondary to their political positions.

I noticed at the tail end of the Morrison government some widely-shared social media posts speculating about who in the cabinet was a member of Morrison’s Pentecostal church — as if this somehow was an explanation for anything.

Was former attorney general and alleged rapist Christian Porter any less objectionable than others in the cabinet because of his lack of religious beliefs?

The question hopefully is rhetorical.

In relation to the current attack on the right to protest in NSW, what separates Perrottet’s view from others involved in suppression of these rights who do not parade their religious beliefs?

The magistrate, Allison Hawkins, who handed out the gaol sentence, described Coco’s actions as a “childish stunt”, which had caused the “entire city [to] suffer” as a result of her “selfish emotional actions”.

Labor opposition leader Chris Minns was quick to join in, saying: “When you inconvenience literally hundreds of thousands of people … there will be legislative action in relation to that”, and that he has “no regrets” about supporting the authoritarian measures.

Will knowing their religious affiliations – or lack of them – help us to fight them? I say no.

Focusing on religious beliefs rather than the right-wing political positions of politicians is a big mistake.

Does Anthony Albanese get a free pass for his massive subsidies to the fossil fuel industries that are destroying the planet because he is less religious than Scott Morrison?

Are the transphobic and homophobic pieces of legislation put forward by the irreligious Mark Latham, One Nation MP in the NSW upper house, somehow less objectionable than those moved by Scott Morrison in the guise of his religious discrimination bill?

I could go on.

We should be concerned about any attempt to shift politics to the right, for example, the way the far right used the mass mobilisation of antivax conspiracy nuts last year to try to build their numbers. And we should resist it.

But locating religious belief as some kind of original sin won’t help us in that.

And lastly, Diane, as we’ve been dealing with the historical, if we take a look at the extreme laws the Perrottet government has rolled out in order to stamp out climate action, how does history tell us such circumstances will play out?

What we can learn from history is that oppressive class societies, whether the slavery-based Roman Empire or the capitalist system today, based on exploitation of the working class and all the other oppressions arising from that, will generate resistance.

That is the fine tradition in which Violet Coco stands, for instance.

The other thing we can learn from more recent attempts to suppress the right to protest in Australia is that such laws can be defeated – by building resistance that takes back the right by protesting regardless of the laws.

The mass protests that took place in Brisbane in the late 1970s and early 1980s defeated the Bjelke-Petersen government’s ban on protests.

Interestingly, in the current context, these focused on another environmental protest movement, that against the mining and export of uranium and the nuclear industry.

Around the same time, here in NSW, I was also involved in the Gay Solidarity Group campaign to drop the charges after the first Mardi Gras in 1978.

This became, in addition, a civil liberties campaign against any protest having to apply for police permission – the reason the cops had given for smashing up the Mardi Gras in the first place.

The hated Summary Offences Act 1970, which required that police permission be obtained to protest, was repealed as a result.

Much more recently, the Democracy is Essential campaign in 2020 refused to accept that while all other restrictions on mass gatherings of tens of thousands had been lifted, spurious “health reasons” were being used to ban protests of more than 20 people.

Despite arguments from some on the left that “clever” tactics of lots of small groups of 19 could defeat this attack, the campaign defied the ban on demonstrations, and supported Black Lives Matter, trans rights and student protests in defiance of it.

I remember you had a wonderful article interviewing one of my Socialist Alternative comrades Eleanor Morley about how this victory was won.

I feel that we need to learn from and replicate these successes of defiance and mass mobilisation.

One aspect from the 1970s, that is much harder to generate because of the weakened state of the union movement is organised worker involvement – by which I don’t mean a few union officials speaking at rallies, welcome though that is.

As any attack on the right to protest can be used against working class organisations, especially strikes and pickets, this is a workplace issue.

And we should not forget, as union involvement in the anti-uranium movement showed, that the workplace is also where real power to resist attacks exists.

So, rebuilding fighting unions is actually part of the fight to defend all our rights, including civil liberties.