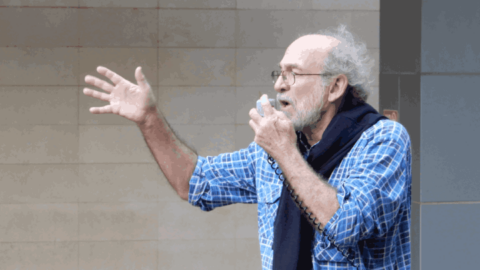

Labor Must Act on Permanent Protection for All, Says Refugee Action Coalition’s Ian Rintoul

The Albanese government announced via the Herald early last week, that it will be granting 19,000 refugees, currently living within the community under temporary protection, permanent visas sometime in the new year.

The 19,000 refugees in question are currently on temporary protection visas (TPVs) or safe haven enterprise visas (SHEVs). And they’re part of what’s known as the legacy caseload, which consists of 31,000 asylum seekers who arrived in Australian waters between August 2012 and January 2014.

So, refugee advocates are now asking the obvious question that develops out of these circumstances, which is what of the other 12,000 people living in the community without permanent protection? When will they be granted full asylum?

Punishing the helpless

Labor went into the May federal election promising to grant permanent protection to refugees who arrived by boat as a key pledge. And advocates are now crying out that the ongoing delay in making the change is causing more suffering to those affected.

“Labor will abolish temporary protection visas and safe haven enterprise visas and transition eligible refugees onto permanent visa arrangements,” states the 2021 Labor National Platform.

The problem for those stuck existing under temporary arrangements is that their lives are restricted in a number of paralysing ways, and, periodically, they have to reapply for new visas, which means existing in a state of insecurity and uncertainty.

The Abbott government reinstated the policy of temporary visas in 2014, which had previously been established by then prime minister John Howard in 1999 and were subsequently abolished by the Rudd government in 2008.

Yet, it was a reappointed Kevin Rudd who established mandatory offshore detention for all refugees arriving by boat in September 2013. And the Abbott government then built upon this with the rollout of Operation Sovereign Borders, which includes the practice of turning back the boats.

Reneging on convention

Going back decades, the policies of successive Australian governments have facilitated the punishing of asylum seekers arriving in local waters by boat. And this seems due to the fact that these people are some of the poorest and most desperate on the planet and that they’re nonwhite.

Indeed, the 1951 Refugee Convention requires signatory nations to provide safe asylum to refugees regardless of how they enter a country. And despite having signed the document in 1954, Australian authorities now prefer to slowly torture those legally arriving by boat via harsh policy provisions.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Refugee Action Coalition (RAC) spokesperson Ian Rintoul about his criticism of the recent press announcement, the issues that temporary visa arrangements pose and how the entire legacy caseload should be extended permanent protection.

Last week, the Herald reported that it had been in discussions with two senior government sources, who explained that Albanese will be ending temporary protection for 19,000 refugees living in the community next year.

You’ve come out saying that the way this election promise is being delivered isn’t good enough. Ian, why is that the case?

There are two fundamental reasons. One is that there is still no timeline. We’ve heard since Labor was elected in May, that it was about to make this decision – that this decision was imminent.

We are now in December and almost into 2023. We’re now told it’s going to be early next year. Is that January? Is it February or March? We still don’t know.

Every day-week-month delay is still an enormous impediment on the lives of people who should have been made permanent in 2013 and 2014.

It means that the refugee legal centres that the government is going to rely on to process these people are still not able to prepare. Being told it is early next year is simply not good enough.

The other aspect is that they’re only talking about 19,000 people.

If we’re talking about the legacy caseload, as all the representations to the government have at least been talking about the legacy caseload, it means 31,000 people in the community, not just the 19,000 who are on temporary protection visas or the equally temporary safe haven visas.

There are also people who have not received decisions yet. In formal terms, there are still people being processed for temporary visas without any decision and around 10,000-odd people who have been rejected under the fast-track system the government admits was flawed.

They’ve now abolished the AAT. But they’ve said nothing about the people who have been rejected on the false and flawed basis of an AAT appeal of the fast-track system.

As far as a lot of people on the campaign are concerned, last week’s announcement looked like a publicity announcement, not one of any substance which is going to change the lives of people who have been waiting too long already.

What does the policy of only granting temporary protection to refugees have upon those living within the community?

The most immediate thing is the question of family reunion, because, whilst on temporary protection visas, they’re not eligible for family reunion of any kind.

So, you have people who have been separated from family for 10 to 12 years because they’re still temporary.

And there are all sorts of implications to just getting on with life. They’re not allowed to study. So, they’re excluded from university and TAFE, which limits the possibility of establishing a career.

If they apply for a house or a job with a temporary visa and not a permanent visa that also has implications.

And people have been having to renew these temporary visas when they expire every 3 or 5 years for the last 12 years.

There are questions of travel. The one thing that they’ve made a policy announcement around is that people on temporary visas can now travel internationally, which holds the possibility of meeting with family that they’ve been excluded from. But that’s the one change.

Put bluntly, it just means that they’re stuck in limbo, and they can’t get on with their lives.

They’ve got no security or the possibility of knowing that they have a secure future in Australia, with the possibility of living with their family and educating their children.

In a letter to the Herald last week, Grandmothers for Refugees co-chair Jean Ker Walsh posed the question whether the change to permanent protection will mean that some of those sent offshore will now be considered for residency for the first time.

And the advocate further pointed out that former offshore detainees now living in the community are being hassled to leave the country, even though they came on the same boats as other people being considered for permanent protection.

Can you talk on these points?

It’s a point that we’ve made as part of our representations since 2013: not only was there offshore detention but there was always a fundamentally discriminatory aspect to that as only half the people who arrived after the announcement in September 2013 were sent offshore.

So, you do have people now who arrived on the same boat from the same country and the same city – so effectively, the same case – being treated differently.

When Labor finally makes the decision to grant permanent visas, the people who were offshore in Manus and Nauru under existing policies will never be made permanent.

There is a fundamental problem with that, and that’s why you can’t just talk about the 19,000 people.

The government can make an announcement about the 19,000, but there are so many more people who have been affected by the same decisions, but those cases aren’t being addressed.

Under existing policy, people who were offshore and might now be married to Australian citizens and be the parent of Australian citizens are not eligible for permanent residency.

So, there are some fundamental anomalies, which the refugee movement sees as unfinished business in regard to the Labor government.

Is Labor going to address these anomalies and injustices that are associated with the policies of the Coalition?

In your opinion, how should our government be treating the 31,000 refugees living in the community long term under temporary protection?

The most sensible thing to do would be to simply grant them permanent visas. But we have not been told how they’re going to go about dealing with the 19,000 people.

Are these people going to have to make individual applications? Could we be waiting another two years while they’re processing all those applications to become permanent residents?

The best thing would be to do what they did to the Biloela family, which was a simple departmental decision that granted them permanent visas.

Why would we put thousands of people who have been through absolute hell – existing without permanent visas, without any income support and without the right to work for the last 10 to 12 years – through another procedure of having to prove their credentials?

These are people from Afghanistan, Iran or Sri Lanka. They should never be sent back. It would be a very easy departmental decision for all those 31,000 people and the others to be granted permanent visas.

They should have got permanent visas when they came in 2013. The fundamental injustice that has been inflicted on them is one of governmental policy, not of their claims or their making.

Both in terms of Australian justice and the humanitarian argument, they should be granted permanent visas.

And lastly, Ian, once the government stops dragging its feet on ending temporary protection as it promised last election and it makes the changes, where will the refugee issue have progressed to, and what will be next on the agenda for the campaign?

There is still the question of the people offshore. The fact is we still have 180 to 190 people still in PNG and Nauru, who shouldn’t be there but should be in Australia for all the reasons we have already been over.

That’s the immediate thing, the situation of those people. But it also needs to be said that we still need a fundamental change in law.

The fact is that if you’re a Rohingya who arrives in Australia by boat under existing Labor policy, you could end up in Nauru in the same offshore situation as we had in 2013.

There is a fundamental problem still with the discrimination against those arriving by boat seeking asylum in Australia. That has to change.

Regardless of how they arrived, people should be processed in Australia. They should be able to live in the community while their claims are being processed and if they are found to be refugees, they should get permanent residence in Australia.

So, we’ve still got quite a bit of unfinished business. And there are still people in detention that shouldn’t be there, and they’re not off our radar either.