Minister Rejects Justice Reinvestment

Federal Justice Minister Michael Keenan has rejected calls for an overhaul of the prison system, reiterating his view that imprisonment is an effective means of crime prevention. Mr Keenan was responding to a Red Cross-backed report which argues that Australia requires a re-think of the principles behind our broken criminal justice system.

Is there a problem?

The Australian Red Cross report emphasised that a focus on crime prevention and reducing the prison population could save taxpayers $3.5 billion over five years. Particular criticism was levelled at the common practice of locking up people for minor crimes such as traffic offences, fine default and low-level property damage.

It costs Australian taxpayers an average of $292 per day to keep an inmate behind bars, equivalent to just under double the average Australian’s daily earnings of $160. These costs are significantly higher than the cost of community-based supervision, which is just $52 per day. The total cost to the community of incarceration in Australia is $3.4 billion a year.

The Red Cross recommends that governments fund justice reinvestment trials in areas of high crime, and commit to a 10 per cent reduction in adult imprisonment rates over the next 10 years, with a 50 per cent reduction target for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders within five years.

What is Justice Reinvestment?

As outlined in previous blog, Justice Reinvestment is an initiative that aims to shift spending away from the prison system and towards addressing the underlying factors behind criminal conduct. This would involve a community-based approach which addresses the risk factors of crime such as poor education, low employment, substance abuse, and mental health issues.

As an evidence-based process, justice reinvestment focuses on creating the greatest change from the funds at its disposal. This is why community-based initiatives are targeted at the ‘million-dollar blocks’ of disadvantage, criminality and reoffending. In Australia, communities with large Aboriginal populations are particularly suffering from current corrections principles.

The demographics of NSW’s youth incarceration rate demonstrates this disadvantage. 56% of juveniles detained in NSW are Aboriginal while the Aboriginal population of NSW is 4.4%. The NSW average daily Indigenous juvenile detention rate (48.9) in 2013 was almost 29 times greater than the equivalent non-Indigenous juvenile detention rate (1.7).

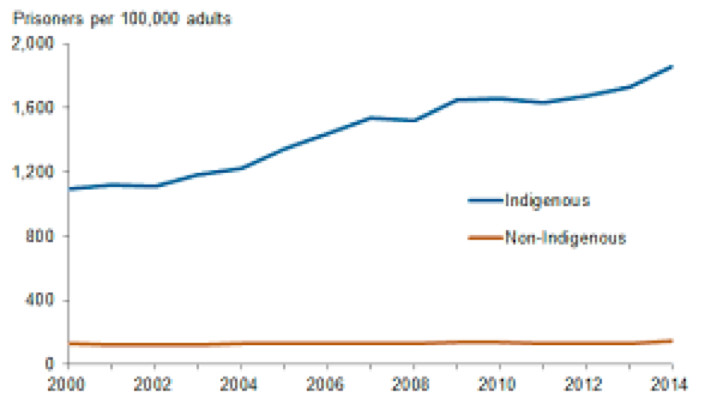

In terms of the overall disadvantage in the adult prison population, Indigenous imprisonment has risen as a percentage of total imprisonment consistently for the past 14 years.

Even before the popularisation of Justice Reinvestment principles in Australia, leading lawyers and criminal justice experts were decrying the ineffectiveness of current policies. In 1998, Tony Fitzgerald QC, a Judge of the Queensland Court of Appeal, commented that the justice system is “… a hopelessly blunt instrument of social policy and its implementation by the Courts is a totally inadequate substitute for improved education, health, housing and employment for Aboriginal communities.”

Does Imprisonment work?

“The idea that locking bad people doesn’t work is not true. It does, we know that for a fact,” Mr Keenan said in response to the Red Cross report. However, Keenan’s remarks are inconsistent with just about every study ever undertaken into the effectiveness of systems which focus on imprisonment.

If Mr Keenan were correct, the current system would be reduce reoffending. In fact, the opposite is true, with the current system resulting in horrendous recidivism rates. Of the 42,239 people released from Australian prisons in 2013/14, the Red Cross report found 60 per cent had previously been released from prison, with 38 per cent reimprisoned within two years of their release.

Recent research has shown that this is not merely a correlation, but that incarceration actually leads to reoffending because low-level offenders come out worse in a range of risk factors, including employment prospects and mental health issues. True longitudinal studies are now beginning to paint youth incarceration as an independent variable causing adult offending. A 2013 study of around 35,000 young people in Chicago showed that incarceration itself made reoffending more likely. Young offenders who were incarcerated were, all other things being equal, 22-26% more likely to be incarcerated as an adult.

The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics (BOCSAR) recently release a report comparing the effect of prison versus non-custodial penalties on re-offending rates. BOCSAR director Dr Don Weatherburn remarked that the results were consistent with a growing body of evidence suggesting prison either does nothing to deter offenders or increases the risk of re-offending. “The present study simply shows that sending people convicted of assault or burglary to prison is no more effective in changing their behaviour than putting them on some form of community-based order,” he said. “It might in fact be slightly worse.”

An argument for imprisonment is that is has a general deterrence effect, where prison sentences stop other people from committing crimes. This is not the view, however, of Chief Justice Tom Bathurst, who has commented that general deterrence should not be a factor in sentencing because there was no ”persuasive evidence that it works”. Assuming that most criminals conducted ”a rational assessment of their planned illegal behaviour”, weighing up potential gain with potential penalties, bore ”little resemblance to reality”, he said.

Skewed priorities

Despite the evidence, public spending continues to focus on imprisonment. In 2011–12, for every $1 spent on community corrections per offender per day, approximately $10 was spent on offenders in prisons. The historical response to growing incarceration has been to ‘double down’ on a punitive, corrections-based strategies by building more prisons, introducing harsher sentences and stricter bail laws. This approach treats the symptoms of crime – ignoring the broader drivers of criminal behaviour amongst disadvantaged communities, which, if left untreated, continue to manifest in high rates of offending..

Western Australia’s Shadow Corrective Services Minister Paul Papalia pointed out that justice reinvestment was about more than increased spending on health or education. “It’s about science, it’s about evidence-based response to crimes,” he said. “You monitor what you’re doing, and if it doesn’t work, you stop doing it.”

Does preventative spending work?

In the face of the research, Mr Keenan claimed there was correlation between increased services and reduced crime. “If there are things we can do to reduce crime before it happens, then certainly we would do that,” he said. “I would never suggest making an investment in some sort of amorphous set of social infrastructure would result in a decrease in crime.”

Most of the research into Justice reinvestment has taken place in the US, and while it is quite a new field of study, the interim outcomes from participating JRI states is already very promising. A 2014 report demonstrated that seventeen states are projected to save as much as $4.6 billion through policies designed to control corrections spending and prevent crime.

In terms of individual States, Texas, being the highest incarcerator, was the biggest winner out of the initiative. After a 300% increase in prisoner numbers between 1985 and 2005, the State turned to Justice Reinvestment principles. By 2008-09, the State had saved $210.5 million, while dropping prison numbers will result in a further saving of $233 million as it will likely be unnecessary that the state will need to fund the building of three new prisons on the basis of previous projections. Texas currently has its lowest crime rate since 1968.

Even individual cost-benefit analysis showed the potential of preventative spending. The Washington Institute for Public Policy has analysed many of the policies put forward by a justice reinvestment framework. In terms of every $1 spent on preventative programs, the following benefits were felt by decreasing offending and increasing pro-social behaviour:

- Education and Employment Training- $34.50,

- Family based therapy for young offenders- $22.96,

- Aggression replacement therapy- $11.69, and

- Cognitive behavioural therapy- $9.27.

Given these findings, it is hard to see where Mr Keenan gets his facts from. It could merely be that serious reform appears too difficult, or is politically unpopular.

Whatever his motives, the research makes it clear that the current approach is bleeding money from taxpayers while doing nothing to reduce offending, while the alternative has enormous proven benefits.