“My Heart Lies in Seeking Justice”: An Interview With Wiradjuri Lawyer Taylah Gray

Taylah Gray made a splash across headlines last year when she fronted up to the NSW Supreme Court to represent a Newcastle Black Lives Matter protest, as the NSW Police Force attempted to silence the 5 July First Nations rights demonstration via a court order.

The 24-year-old Wiradjuri woman has recently caused a stir once more, and this time it’s over comments she made regarding racial bias in the Australian education system, on the same day that her name was added to the NSW roll of lawyers.

At a 24 February ceremony at Newcastle’s City Hall, NSW Chief Justice Tom Bathurst remarked that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people remain grossly underrepresented in the legal profession, and more diversity within its ranks will ensure greater justice for the broader community.

Following the admittance ceremony, Gray posted a message on social media, in which she addressed First Nations kids, advising them that as the education system wasn’t built for them, they shouldn’t let it make them believe that they’re “not gifted or talented enough”.

An attempt at suppression

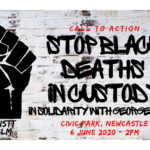

On 3 July last year, NSW police commissioner Mick Fuller petitioned the Supreme Court to shut down a Black Lives Matter protest set to take place at Newcastle’s Civic Park two days later, which had been organised by Aboriginal rights group Fighting in Solidarity Towards Treaties (FISTT).

Then a Newcastle University law student, Gray was summoned to the court, as it was her name on the required official form that had been submitted to NSW police outlining the group’s intention to hold the public assembly.

As Black Lives Matter rose in prominence in mid-2020, NSW police attempted to shut down multiple rallies, as it played the COVID card. But as the protests were targeting police brutality and custodial deaths, others saw a different motivation behind the attempt to silence the movement.

In terms of Gray’s case, NSW Supreme Court Justice Christine Adamson ruled on 4 July “that the public interest in free speech and freedom of association outweigh the public health concerns and that the order sought by the plaintiff ought be refused”.

“Walk with purpose and speak your truth”

Gray further noted in her post addressing First Nations youth that despite having failed her legal studies exams in her senior years at high school, she’s recently been accepted to write a thesis on Native Title law. And she added a warning against letting the system destroy one’s dreams.

Of her future legal career, Taylah made certain that she’s “coming for all our mob who are imprisoned”, and she’s also “coming for land rights because the western world’s most learned diplomats and greatest intellectuals have failed to solve this grave sovereignty problem”.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Taylah Gray about the barriers that the Australian education system poses for First Nations youth, the direction she’ll be taking her inquiry into Native Title in, and how she foresees treaty-making on the horizon.

Firstly, at a 24 February ceremony at Newcastle’s City Hall, you were admitted as a lawyer. On that same day, you went on to post a message addressing First Nations youth, which garnered much attention.

In the post, you also advised that the Australian education system hasn’t been created with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in mind. Taylah, how does the education system fail Indigenous youth?

English, for example, is part of the core curriculum, so it’s a compulsory subject, whereas Aboriginal studies is an elective. It fails in that way, and it also fails through a lack of funding.

There should be more Indigenous educators, so kids can be nurtured in the same way that I was nurtured in the Yapug program, which is what got me into my law degree. It’s a pathway into university.

There isn’t just one thing that disadvantages Indigenous children. It’s multifaceted. The system is layered with disadvantage and oppression.

You’ve been accepted to write a PhD on Native Title law. Over recent years, the Native Title system has come under scrutiny, especially after former attorney general George Brandis introduced legislation that appeared to be all about facilitating the Adani mine.

What aspect of Native Title will your thesis focus on?

It’s going to look at the way in which legislation and racist language has reduced Native Title rights since Mabo.

Although there’s the destruction the Native Title Act has caused, especially with the amendments, at the end of the thesis, I’m going to assist in providing solutions with economic theory.

This will be in ways where First Nations people and non-Indigenous people can use the land together and do so in a safe way for everybody.

It will also look at foreign jurisdictions. It will look at Canada, where they have a treaty with First Nations people, which was how Native Title came about.

So, it will show the lessons that can be learnt from foreign jurisdictions in terms of having a treaty in Australia. And how that would look in terms of land rights and native title over here.

In Canada, those rights were ultimately withered away, even though there was a treaty. So, it will be looking at lessons from foreign jurisdictions.

In your final high school years you failed legal studies, yet you then went on to undertake the Yapug Indigenous foundation course at the University of Newcastle. And late last month, you became a lawyer.

Why have you pursued law?

When I was eight years old, I was in my friend’s lounge room debating a case. I couldn’t tell you what I was arguing. It would have been nonsense. But I knew from that moment on I wanted to be a lawyer.

One thing that has really driven me to achieve that is my father. He is a Stolen Generations survivor. He was forced to sit at the back of the classroom. Now, when I go to university, I sit at the front of the classroom in the lessons that I attend.

My father was a critical reason for me going into law. But not only that, community as well. Community has strengthened my ability and identity. And my heart lies in seeking justice.

In July last year, the NSW police commissioner took you to the Supreme Court to try and get a prohibition order issued against a Newcastle Black Lives Matter protest that you were organising as a member of FISTT (Fighting in Solidarity Towards Treaties).

How did you take the police trying to shut it down? And what got your argument across the line?

How do you think I took it? That case was set up to silence black voices and to harm black bodies. I felt frustrated – but I was motivated too.

Since then, I’ve developed a working relationship with some of the police officers from that department.

At the last protest that we held on the 26 January, Invasion Day, one of the police officers marched in the front with me. And he engaged in the smoking ceremony. That has been a real turning point.

But what got us over the line was community. Not just First Nations mob but also our allies. They helped in making sure it was a COVID safe event.

Everybody got us over the line. The legal team as well. Barrister Felicity Graham helped substantially. We were up until 1 o’clock in the morning going over an affidavit. So, it was a community effort.

You subsequently addressed the 6 July BLM protest in Newcastle’s Civic Park. And in doing so, you outlined a reform plan that would deliver better justice outcomes for First Nations peoples. What does that plan consist of?

There were 10 key points. They weren’t all mine. There were some community concerns. They included restricting the LEPRA Act, making sure there’s a separate investigation where police aren’t investigating police, and the main one was treaty.

You posit that the Australian education system hasn’t been established with Indigenous children in mind.

What’s your take on how the Australian criminal justice system has been set up in terms of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

All we have to do is look at the rates. We are the most incarcerated people not just in Australia, but in the world. That says enough.

And lastly, Taylah, you state that you’ve found your role, which consists of “using the vehicle of the law to seek justice” for Aboriginal communities. What would you say this is going to look like moving into the future?

Treaty. It’s going to look like treaty. It’s going to look like non-Indigenous and First Nations people using the land together.